Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

It fascinates me to hear stories about the construction of EPCOT Center, which was a mad dash nearly on par with the original Disneyland. Some attractions failed to make the opening date of October 1st, 1982, while others barely reached it. Engineers and countless other staff members worked around the clock to build this incredible new theme park. Unlike The Magic Kingdom, Disney was not building a larger variation of a park already in place. EPCOT Center’s attractions were all customized and did not have an obvious connection to previous work. My guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast is Steve Alcorn, who worked as an engineering consultant for Disney in 1982.

His primary assignment was The American Adventure, which used an extremely complex show system. Steve has remarkable stories about the chaos of construction during that time period. The young team dealt with huge odds against them and succeeded despite the challenges. Steve also worked on the Imagination pavilion and Horizons prior to their openings in 1983. Steve is also the CEO of Alcorn McBride Inc., which has provided video, audio, and show control systems at theme parks for more than 30 years.

A Fun, Detailed Look at EPCOT’s Past

Our fun conversation includes a discussion of these topics:

- How did Steve get started in theme parks and working at Disney?

- Why was The American Adventure such a complicated system?

- How chaotic was the EPCOT Center construction site in 1982?

- What was the big challenge in making the Journey Into Imagination ride work?

- How has the theme park industry changed in the past 30 years?

- What are the ways to keep screen-based attractions from becoming obsolete?

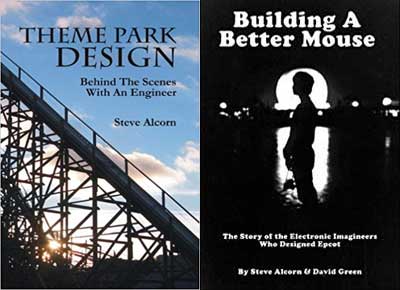

It was a real treat to speak with Steve about his experiences working on EPCOT Center and more. You should check out his books, Building a Better Mouse: The Story of the Electronic Imagineers that Designed Epcot (which focuses on EPCOT Center’s construction) and Theme Park Design: Behind the Scenes with an Engineer.

Show Notes: Steve Alcorn

Learn more about Alcorn McBride Inc., all of Steve Alcorn’s books, and his Imagineering class.

This post contains affiliate links. Making any purchase through those links supports this site. See full disclosure.

Transcript

Dan Heaton: Hey there. Today we’re talking about the construction of Epcot Center. Steve Alcorn is here. He was an engineer at Epcot Center in 1982. You’re listening to the Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks so much for joining me here on Episode 43 of The Tomorrow Society Podcast. I’m your host, Dan Heaton. We’ve all heard a lot of stories about the crazy opening of Disneyland and the rush to even get it ready with Walt pushing his crews overnight and just doing so much in 1955 to even make the opening day.

And of course that didn’t go very well. We’ve heard a lot of famous stories about shoes getting stuck in the sidewalk, you know. They had no water fountains so they could have bathrooms. It was a crazy opening day. And of course, we all know how that actually turned out at Disneyland. It’s a legend, especially because Walt was directly involved.

Now an area we don’t hear as much about unless you really study it, is the opening of Epcot Center. Particularly the rush before the opening on October 1st, 1982, to even get the attractions close to being ready. You had some attractions that were delayed till the next year. Others that didn’t entirely work on the early days.

And the chaos involved with building all these new attractions and pavilions, many that used technology that hadn’t been used before or not at this level. And in the book, Building A Better Mouse by Steve Alcorn and David Green. When I read that, it was an eye-opening experience. I had no idea that the staff had to work such crazy hours.

It makes sense in hindsight, but you just don’t think about it when you go to Epcot. Now, how much work was involved to even meet the short timeframe? It did not take that long to build that park. We think now of attractions that can sometimes take three to four years to build. This was not the case with Epcot Center.

And that’s why I’m really excited to talk to my guest today, Steve Alcorn, who was a consulting engineer on the Epcot Center project, and has some great stories about what it was like to work within that chaos of trying to get these attractions up and running. Steve also has been working in the theme park industry for a long time with this company, Alcorn McBride, so he has interesting insight into the way the industry has changed over the years.

So it was a real treat to get to talk to Steve, and I think you’re going to enjoy what he has to say, especially about Epcot Center. Some of his stories were ones I had not heard before, so it was very exciting to me, who reads a lot about Epcot Center, to find out some new information, and let’s get right to it. Let’s talk to Steve Alcorn.

(music)

Dan Heaton: All right. Well, I am here with Steve Alcorn, who is the CEO of Alcorn McBride Inc. He’s also an engineer. He’s worked in the theme park industry for more than 30 years, including at Epcot Center in 1982 prior to the opening day, and he’s written books like Building a Better Mouse with David Green and Theme Park Design: Behind the Scenes with an Engineer. Steve, thanks so much for being on the podcast.

Steve Alcorn: It’s my pleasure, Dan. Good to join you.

Dan Heaton: Great. So before we dive into all your work, I’m curious about your background. How did you get started in the theme park industry?

Steve Alcorn: I kind of refer to myself as an accidental engineer because, my original plan was not engineering at all. My father was an engineer in the aerospace industry and back in the sixties, that was a pretty uneven place to be. So my mother always said, don’t be an engineer. It’s the worst job in the world. So when I went into college, I started off in economics and figured I’d ultimately be a lawyer or something about the same time.

I met my future wife, Linda McBride, when she applied to UCLA the year after me, she found on the application form a check box for what you were interested in, and her father was an engineer in aerospace also. And so without thinking too much about it, she just checked the engineering box. Well, it turned out that that caused her to be put into the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at UCLA.

So, I wanted to spend more time with her and I wasn’t too happy with my economics curriculum. So I decided to transfer into engineering to spend more time. And as a result, I turned out to be an engineer and she knew what she was gonna be from the time that she was in the third grade when she was entered in a school science fair and built a model of Disneyland in three dimensions.

She always knew she was going to work for Disney. She just didn’t know doing what. And so she was the one that first started in the Disney Imagineering endeavor at WED Enterprises in 1979. She was the first female engineer. And I just followed her in when it became apparent that she was going to spend a lot of time in Florida working on Epcot.

I came on as a consultant in early 1982 to help with the American Adventure. So my whole career is kind of based upon the fact that I followed my wife into the field of engineering and then followed her into the field of theme parks.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s really interesting. And it sounds like she obviously had a big affinity for Disneyland and theme parks. Before all of that, when you were a kid, did you spend much time in theme parks at Disneyland or other other parks?

Steve Alcorn: Not as much time as she did, but certainly growing up in Southern California, Disneyland was the regular venue for celebrating birthdays. It was the regular venue for graduation nights from high school. And also I, while I was in high school, in college, I was actually a dance instructor at the Beverly Hills Cotillion, which is where I met my wife. And we actually took dancing lessons from the World Champion dancer at the time, Ken Sloan, and we used to go down to Disneyland and dance at the Carnation Pavilion as part of Cotillion outings and so on.

In fact, we were good enough that occasionally, people would clear the floor and we would dance and they’d throw dimes at us as a joke.

Dan Heaton: That’s great. That’s a fun story and I’m a little jealous that you were so close to Disneyland growing up. So what was it like when you both worked down there? I mean, just talking a little more about like, did you have any time to have any type of normal life when you were both down there working, getting ready for Epcot Center?

Steve Alcorn: Yes and no. We’re both electronic engineers and so historically our pillow talk has been a little bit weird because it’s always about technology and control systems and so on and that. It was no different before or after the project. What was different was the working environment and the hours. When we were in the heat of getting that park ready to open, we didn’t have personal lives at all. I mean, we were working 100 hours a week during the summer of 1982 to get the park open.

All you have to do is look at pictures of that construction site from the spring of 1982, and it looks like a park that can be opened with no problem at all in about two years. And knowing what we know now about the theme park industry, there’s no way we would’ve even tried it. But we were all too young and inexperienced and dumb to know that it was impossible.

And so we just did it. But looking back on it, I still really don’t know how it happened, other than the fact that there were thousands of people putting in those kinds of hours, and we were all young and energetic and dedicated to making it happen. During that time, there was no private life. We wouldn’t even go home to our trailer in Fort Wilderness a lot of the time.

I remember many nights sleeping on the floor of the pit in American Adventure or up in what would become the VIP area. And they would just bring in meals because there were no restaurants or employee cafeterias anywhere around. So they’d just keep feeding you to keep you on the site so that you could work. And we had an around the clock schedule.

We had enough of a schedule that there was one time a day when the crew on American Adventure could all get together and meet at the same time. We were all working 16-hour shifts, but they were all misaligned. Except for this one-hour period where we could get together and coordinate, but it was around the clock seven days a week through that whole summer to get to opening day on October 1st after the park opened.

Then Linda and I did have a bit of a personal life because from then on, all of our work had to be done at night after closing time. And so we lived this rather odd existence where we would sleep during a lot of the day, and then we would get up in the afternoon or evening and we would go out and have a nice dinner sometimes far away.

We’d go down to some of the nice restaurants that were not near the property at that time. Spinelli’s and St. Cloud was a favorite. They had a big wine list. We’d go down there and have a nice dinner, and then we’d come back to the park about an hour after closing time, after the maintenance guys had done whatever they needed to do.

And it was really a neat time because we had this whole theme park at our disposal to play with. And we could just tell the maintenance guys for whatever pavilion we wanted, you know, bring the ride up tonight and we’re gonna be working in there until three, four o’clock in the morning or whatever.

We had the attraction to play with, run the shows, reprogram the show control systems, ride the rides, check the audio and everything. We just had to make sure that everything was working perfectly by the time that we left in the morning. And we had to get out of there about an hour before park opening time in the morning so that they could go through their startup procedures.

So Linda and I both remember things like lying on the floor of the pre-show for Magic Journeys and Imagination, running the making memories slide presentation to make sure it was still working before the park opened and thinking, you know what, these are the good old days when you can lie on the floor of the pre-show and enjoy it all by yourself.

Dan Heaton: Oh man, that’s amazing. I don’t even know what to say for somebody who…I went as a kid to EPCOT Center, but looking back at it now, to be in your like twenties or to be an adult and to be able to just kind of, I know you were working very hard, but also have those moments where you could play a little bit and just enjoy that area.

That’s incredible. I love that story. And you mentioned about, you know how crazy it was and I know you write in Building a Better Mouse, you have, you and David have just great descriptions of just how nuts that was. Like the pictures, like you said from that. It’s incredible that yeah, now it takes, sometimes takes three to four years to build a single attraction.

To build a whole park in less than that is, it’s just insane. So you mentioned that you were too dumb to not realize it, but I mean, how crazy was that environment? How were you able to cope with doing these complicated show design while you were on no sleep and were kind of not on a normal schedule?

Steve Alcorn: Well as you say, we were young. Almost the entire engineering department was in their twenties, and we really literally didn’t know how a normal theme park would be built because we, none of us had been with the company and almost the whole old guard that had been with the company in 1971 when the Magic Kingdom opened, they were gone.

And so we didn’t hear their war stories and we didn’t know how long that park took. And it also was fast-tracked, but of course it was far, far simpler and smaller than Epcot was. It was the first time that most of us had been to Florida. Basically we flew into the airport and we drove to Fort Wilderness, and the next morning we got up and we went to the site and we just started working and the work environment was.

Crazy but amazing in those days. Because in those days, Disney treated you like a king or a queen. You had a rental car, and if it broke, they just brought you another one. No matter what you did to it, they didn’t want you to lose any time you flew first class across the country or you flew on Walt’s plane, the mouse.

You were put up at Fort Wilderness. You had per diem. They were feeding you too to, so that you didn’t even have to spend your per diem. You were too busy to spend your per diem. We all ended up with lots of savings. Heck, Linda and I pooled our savings after two years of business trip and, uh, ended up buying some apartments down here, which turned out to be a lousy investment.

But it gives you an idea of how we couldn’t really spend any money during that time. We were just working all the time. You would drive your rental car, wearing your steel towed boots covered in dirt, the whole thing. The the rental car would have an inch of dirt on the floor of it. You’d drive it out onto the site.

There were no roads. There was no pavement at that time on the site, and you’d try to get as close to where you needed to go. I remember going out to the base of Spaceship Earth to help out with the motors that are in the track that Reliance Electric was installing, and I was looking for the guy from Reliance Electric park my car under Spaceship Earth, go up, climb up the down ramp, finally find the guy, have a conversation, come back down, and half of my car has been buried by an earth mover that just moved a mountain of dirt over and I could barely get the car out of the spot that it was.

And even walking around, you know, it would take 30 minutes to walk from the World of Motion side over to the Canada side at that time because you were climbing over mountains of dirt and dodging earth movers and hoping you weren’t killed and your body never found again under a mountain of dirt in order to cut across the property like that.

Dan Heaton: It sounds, it sounds insane. Just trying to picture Epcot as a mound of dirt and, you know, steel girders and everything just, just amazes me to no end. So have you experienced anything similar to that? Could they even, I mean, you couldn’t even have a project like that right now with so many regulations, I would assume, right. Have you experienced anything like that? Or is this, was that like a singular project probably ever.

Steve Alcorn: Well, in many ways it was a singular project just because of its massive scope, because it was the first one and because we were involved all over the property. So it was in a way, like a private theme park.

But I have had a few experiences since then that were kind of fun. And so has Linda when she was bringing up. The Indiana Jones Attraction at what was then Disney MGM Studios. They had a lot of nights playing out there with the gas explosion effects, trying to set the telephone pole on fire and see how high they could blow, traffic cones up in the air from the explosions and so forth, so you can have fun on a normal installation.

But that was another installation where about eight months before that park opened, they decided that they didn’t have enough attractions in it, a situation that has persisted until today and they decided they needed another one, and so they literally put that Indiana Jones Stunt Show onto the schedule eight months before opening. They had to design and build that whole thing in that length of time.

So it was another situation of what we call the money cannon being loaded, where it doesn’t matter how much you spend, it just has to open. And that was certainly the case during Epcot, where they started with a $400 million budget and we ended up spending $1.2 billion, but it didn’t matter. They just wanted it opened, and so the checkbook was open and we could spend as much money as fast as we could.

In some ways, that makes projects more efficient, oddly enough, because these days, the problem that they have. It’s an awful lot of time is spent in meetings and planning and on overhead that never gets into the final attraction. And so in those days, most of the dollars that were spent ended up where the audience could see them in the attraction because there wasn’t enough time to plan it any better.

So although we had to expedite everything and waste money on over nighting tons of equipment or whatever, it still ended up, I think, a richer attraction with more quality in the actual materials. Another really fun installation experience that I had where there was a little bit of pressure to get things open but I did have a whole park to play with was Lego Land in Carlsbad, California. And in that case, our equipment from Alcorn McBride was used in all the attractions around the park to both control the attractions and to play the audio.

But because of the fact that especially at that time, Legoland was not yet quite the size and sophistication of a theme park operator that they are now. They hadn’t attended to all of the details that would normally be part of a Disney or universal project. And as a result, we were out only a few weeks from opening, running around as usual, from attraction to attraction, downloading new software, and realized that we didn’t really have a, a lot of the media that was going to be required.

For the park, a lot of the audio and so on hadn’t been made. So I had a lot of fun because I’d run back to the construction trailer and the Internet was a thing by then, unlike during Epcot. And I’d go out and I’d find sounds of swords, clanking, or metal hitting together and I’d mix it all together into a sound that made it sound like it was a sword fight, and then run out and install it into one of our digital bin loop audio players in order to provide the audio.

I think a significant portion of the incidental sound effects around that park ended up things that I just threw together on my laptop. So it was kind of fun to not just be the show programmer, but also to be the ad hoc audio media guy for that attraction.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that sounds like a blast. I haven’t been to that Legoland, but just being able to work on something like that because it really proves you have to do so much you’re on your toes, but in some way I’m sure that’s gotta be so much fun. Pretty much I could ask you about a hundred questions about what you just said, all those different things, but they’re all great. I want to dive in a little bit on your statements about the differences, because one of the things right now that we, and I’m sure you, you see this being in the industry, is that it does seem like some attractions take so long and you see attractions that are super complicated.

But some that aren’t, that still cost…you mentioned in one of your books like a hundred million dollar cheap attraction in a way. So I mean, is there anything, I think one of the issues might be that just like Disney and Universal especially are so big, but is there anything they could be doing, obviously fewer meetings, but are they just too large to work in that same lean way? Are there adjustments they can do? Are they just kind of stuck?

Steve Alcorn: That’s a difficult question to answer, and I think if anybody had a really good solution for that, they probably would be a CEO and would be solving that problem. There was a culture shift, no doubt. After Epcot when you lay off 195 people out of a 200-person department it’s going to change its character a lot.

When you put it back together again for the next project, if you don’t put it back together the same way, you’re going to have a different culture. And unfortunately, during the late eighties and early nineties, WED went through a stage where they were bringing in a lot of people who were ex-military people who were very oriented towards the process rather than people during Epcot.

We still had the remnants of some of the old guard who’d been there when Walt had been there, and they did things the way that they had been done when Walt was there and that philosophy was lost. As soon as you start having all sorts of processes put into place, it becomes hard to get the job done.

I know my wife retired after close to 40 years with the company, and she loved when she was doing her actual job, which was designing show control systems, but it got to the point where she was only spending 5 or 10% of her time doing that, and a lot of the rest of the time was spent trying to deal with getting reimbursed.

If you’d had to go out to buy something on your corporate credit card or to attend meetings to discuss the budgets and schedules and meetings with planners at many different levels. Just the general overhead of attending HR classes and all of the burden safety classes, things that have been laid on.

Now to go into an attraction, you have to pretty much be wearing steel-toed shoes and a safety vest and a hard hat, and there’s all these regulations, and this is just to go into work on a cabinet. You can’t really effectively do the job of an electronic engineer if for example, the rules say that the power has to be off on the cabinet while you’re working on it.

Well, if the power is off, you can’t work on your equipment. All of these things that we took for granted back in the old days, have now become rather burdensome, and I think they’re symptomatic overall of the amount of management and compliance and structure that has been applied to the process. And so it’s a little frustrating for us in the old guard.

We understand from liability reasons and compliance reasons why a lot of this has to be done, but it still gets frustrating and we are always trying to find ways to get more of the money to actually end up in the finished product. On the bright side, there are now many outside companies that can provide materials and services that make the job much easier than we had at during Epcot.

During Epcot, we were designing from the circuit board level up everything that had to go into the control systems, the audio systems, the video playback systems, you name it. We were working from chips to circuit boards to rack level to cabinet level, building everything ourselves, designing everything ourselves.

Now you can go to companies like my own Alcorn McBride, and you can buy a ride player, which is a box that can go onto a ride vehicle, that can source 16 channels of sound. Mix it together, has show control built in, has amplifiers built in for all of those channels, can communicate digitally and wirelessly with all of the other devices in the building to synchronize the vehicle with the wayside systems, and it’s just one single box.

You can mount it onto a rollercoaster, it won’t fall apart. You can mount it onto a motion base and drive it around a building. So these tools are things that were not available then, and that makes the job of Universals, the Disneys, the Six Flags, the Legolands infinitely easier than it was back in the day.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that’s a really great point because you described in in your books about how with Epcot, you were doing so much customization and of the technology, which can lead to great things, but companies like yours that specialize now, especially given the way the technology is changes, that has to be something that’s a really positive thing in general for, for things working better. Not that things didn’t work at Epcot, you guys just had to do a lot of work to get it there.

So I want to ask you, speaking of Epcot, about your work on the American Adventure, because that show, to me, my mind is still kind of boggled by how complicated that show is and how well it works. So can you talk a bit about some of the issues you guys faced even getting that ready for near opening day?

Steve Alcorn: I like the way you said near opening day because I don’t know that we actually ran it all on opening day, but we did get it working pretty soon after opening day fairly reliably, which given what had come before was a miracle.

I know that I spent the night before opening day on the floor of the pit dozing and restarting the attraction, cycling it all night long because we had learned that if the hydraulic oil cooled off, then it, the lifts wouldn’t run reliably anymore. So all night long, I kept it running. And then Glen Burkett, who was the electronic engineer in charge of that project, came in to relieve me.

And I went home and I went to sleep. I slept through the opening day activities only to find out that about an hour after I’d left, the thing had gone down anyway and they hadn’t been able to get it back up again. So yeah, American Adventure is complicated because there are so many potential collision points of the equipment that makes it work.

The way that it works is that there’s this giant carriage that weighs something like 400,000 pounds. And it’s big. It’s not quite as big as a football field, but it’s darn big. And it rolls underneath the audience to get it out of the way and indexes so that these hydraulic lifts on it can come up in the right spot in front of the stage.

And those lifts are 14 feet high and they rise 14 feet out of the carriage, which in itself is kind of a good trick and they have to do it in 10 seconds and they can’t come up under the audience, or they would squish the very expensive animated figures that are on them, and they can’t come up underneath the rear projection screen because that would crush the whole structure that holds the rear projection screen, as well as destroying the animated figures.

But once they’re up, also, the carriage can’t move by accident, or it will slice those figures off of the top, whether or not it moves underneath the audience or farther back underneath the rear projection screen. There’s 10 lifts on it, and each lift had originally something like 15 different hydraulic control valves that had to be sequenced in a very precise order, which was pretty tricky in a day before IBM PCs were something that you could buy and use in order to control stuff.

So that was all custom. And then, just to complicate things a little further, some of those lifts have props on them that also can come up and interfere with things. For example, the sign on top of the depression set could come up, and it’s not controlled by the lift controller system. It’s controlled by a show control system that is animating the figures on that depression set.

And also, if that sign doesn’t come down and you move the carriage, then it shears the sign off. There’s a lot of things like that. Then to add to all of that, the Frederick Douglass raft set, which also has Will Rogers on the back of it, is another smaller carriage, and that raft is tipped down to get it out of the line of sight most of the time.

So if that small carriage moves forward, it will smash that raft into the large carriage. Or if you float the raft over the large carriage and then accidentally lower it, it will smack down into the large carriage. Or if you accidentally tell Chief Joseph’s set to come up while the raft is still over, the large carriage, Chief Joseph will come up and hit the raft on its way up. And that one we actually did during a show. There was an audible gasp from the audience when that happened. But fortunately we only clipped a little bit of the base of Chief Joseph. So it didn’t do too much damage, but there are all these different collisions. So as a result, we ended up not using the normal show control system to control that attraction.

We actually ended up using the ride control system because that was a multiple redundant controller, and if they disagreed as to what was to happen, then the system would shut down hopefully before a collision occurred. Not foolproof, as you can tell from the raft and Chief Joseph collision, but pretty close.

We put limit switches and sensors all over the place to try to keep stuff from running into other stuff, but it’s just immensely complicated, all of the motors and lifts and hydraulic stuff that’s moving stuff around in there. It was a very long time before I could sit and watch that show in the theater and not be mentally willing each one of those lifts to come up into the correct position.

But finally, now that my wife actually has redesigned the control systems in there three times during the last 35 years, I can go in there and feel absolved because I don’t think any of my stuff is left controlling that attraction anymore.

Dan Heaton: That’s great. I can imagine that you just watching and thinking like, did I do that right? Did that work right before you came to that solution with the systems? Were a lot of figures and different sets like damaged or destroyed during the testing? How did you test without, with placeholders? Because I’m imagining people creating Chief Joseph and Frederick Douglass and all the sets not wanting to have their sets destroyed while you guys are testing them. How did that work?

Steve Alcorn: Well, remember the timeframe on this is so compressed that there was no test and adjust time when there weren’t figures there as stuff was available as quickly as possible, it was being put in. We were testing stuff in there on the supposedly dust-free date when the back of the building hadn’t even been built yet, it was still completely open and there was construction dirt on the floor two inches deep in the equipment area where all the electronic equipment was while we’re trying to test the control systems to move the carriage and to move the lifts, and those hydraulic lifts are really powerful.

So although we were lucky enough to never damage any figure in a major way. We definitely did some damage during the testing, the carriage and the lifts on the carriage are made out of steel I beams. They’re probably six or eight inches wide. They’re serious steel I beams and the hydraulics are running at 8,000 psi.

So if you activate those hydraulic cylinders in the wrong order, the thing is as powerful as a front end loader. And so we would literally bend those steel eye beams by accident and then welders would have to come in and cut out the bent sections and replace them with new straight ones. So it was not kidding around.

Dan Heaton: All of this gives me even more appreciation for the fact that it works so well. I’ve seen it a lot of times in each era, probably each at the beginning and then after, and it always worked perfectly. So that even makes me appreciate more what you guys did.

The American Adventure is one of the few attractions there’s a few others from the early days that with changes to the film and to the systems, but is largely similar to what it was. What do you think is the reason for why that has had such good staying power at Epcot?

Steve Alcorn: Storytelling. That’s always the reason that something has good staying power, and it’s the thing that differentiates between a great attraction and one that isn’t so great is that everything always comes back fundamentally to whether or not you’ve got a strong story.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s one of those where I haven’t seen it sometimes for a few years and it really sticks with you and that that’s a testament to the storytelling. So you also worked on Journey into Imagination, I believe, which opened, later in March of 1983. So how was that working on the original version of that attraction?

Steve Alcorn: Well, that was another kind of a mad rush scenario, even though it. was known that it would not make its opening day well in advance of October 1st. There was still a lot of pressure to get it open, but that attraction had trouble getting the vehicles controlled around the track because it was using the same system with motors down in the track that is used in Spaceship Earth and used on the original People Mover at Disneyland.

But the vehicles on it were spaced much closer and could move at variable rates around the track and the vehicles were inserted into this giant turntable in the middle of the building, and the turntable had the ability to crush the vehicles if you didn’t get the vehicle slotted perfectly into the receptacle for it in the turntable so that five vehicles would be in the turntable at any given time moving around seeing the same show.

This is one of those instances like the end of Horizons also, where they went to tremendous expense to get you onto a vehicle and then make you think that it wasn’t moving anymore, which was a concept I really didn’t ever completely understand. They were obsessed with that on those two attractions, and it proved to be really, really difficult in both cases to do it.

So with Imagination. I had still been working on both loose ends at American Adventure and also the park-wide monitor system, which had 30,000 data points from all around Epcot being collected. And that hadn’t gotten done by October 1st either. And because we were aligned upon a particular piece of equipment called the Monitor Cabinet.

In American Adventure to even get that attraction open, I’d had to write my own operating system during the last couple of weeks before Epcot opened in order to get that to work in American Adventure. So when the monitor system still wasn’t working around the rest of Epcot, I started expanding and modifying that operating system so that it could be used in all the other cabinets.

Throughout much of 1983, that’s what I ended up spending my time on, was to bring up the rest of the parkwide monitoring and control system. But I was pulled off of that effort and pulled off of American Adventure to take a look at Imagination. And I had one advantage that nobody before me had had is that they made me the first systems engineer that they had ever had.

And as such, I had reporting to me the ride people, the show people, the mechanical people who had designed the vehicles, even the architectural people and the maintenance people, and I could get everybody together in one room and ask them all why the attraction wasn’t open, which of course resulted in a lot of finger pointing back and forth between all the various things that weren’t working quite right.

But I had the good fortune that there was a young co-op student who was working on the attraction named Jim Carstensen, and he had a pretty good idea of where the system was way overly complicated, and it turned out that they designed Imagination with all of the control equipment down in the track so that when a vehicle was stopped, it was on top of the control system and you couldn’t get to it.

And these things were all over the pavilion and they weren’t working very well. And I got the guy who was programming the ride control computer back in Imagination Central to agree that he didn’t actually need any of those things down in the track if we just connected the little sensors that sensed the things on the bottom of the vehicles back directly to his ride control computer.

He said that he could control all the vehicles on the track directly from that one computer, and we could get rid of all of the rest of the equipment. But he said he didn’t think he could keep the vehicles from bumping into each other. So I turned to the mechanical engineer and I said, is it okay if the vehicles bump into each other?

And he probably to his later regret, said, absolutely. Those bumpers are designed for that. And so that night, Jim Carstensen and I went into the attraction and we moved each vehicle one by one in order to get to the controllers down in the track. We opened them up, we cut all the wires in them, we threw away all the circuit boards in them, and we wire nutted the sensors directly back to the ride control computer in the equipment room. Ten days later, the attraction opened.

Dan Heaton: Wow. That’s, that’s the tight timeframe. I’m sure that sounds like it took some crazy out-of-the-box thinking just because, you know, like you, you said this was not, there’s no handbook for this, this is something you have to figure out. Right?

Steve Alcorn: Well, there’s two post scripts to that story. One is we then spent the next nine months going through 14 different designs of bumpers because he’d been a little bit overly optimistic in how well the bumpers were when you bumped the vehicles together. And the second postscript is that Jim Carstensen has been working for me almost ever since then. And he’s the Vice President of engineering at Alcorn McBride now.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that connection, you guys just worked together better, I guess, or very well for a long time. So I have to ask you about Horizons because that’s one of my all-time favorites. And I know that you went to start working there, you know, before it opened, which was later that year. What kind of work did you do there?

Steve Alcorn: Well, Horizons was scheduled to open October 1st, 1983, and the problem in Horizons was that unlike all of the other attractions around Epcot, it had way more tape starts that were being used to create the audio. In the vehicles, there were over 300 tape starts in Horizons, and each one of those tape starts was triggered by a vehicle entering a particular spot on the track, which sent a message from the pavilion back to Epcot Central because at that time, almost all of the sophisticated electronics, including a hundred percent of the audio sources were located at Epcot Central.

And those audio sources in those days were tape cartridge machines like you’d use at a radio station. And so there were 300 of them and they had to be started at the right time and their audio routed to the right vehicle back out to the pavilion. That was supposed to be done by the monitor cabinet that I mentioned earlier.

But the programming had not been done on all of those monitor cabinets. So that was really the thing that caused us to take a look and say, look, we’ve got to clone this operating system that’s on American Adventure and move it around the rest of the park because Horizons can’t open without that operating system.

So my efforts in Horizons were almost a hundred percent focused on just that one cabinet in order to get those tape starts to work. And we got that going again a couple of weeks before the attraction opened. Those tape starts these days are provided by Alcorn McBride, solid state audio producers in a digital bin loop that is located in the building or they were until the attraction closed.

And that is the architecture that is used all around the park now is that the audio sources have all become solid state and they’ve all migrated out the various individual attractions so that there actually isn’t really any equipment at Epcot Central anymore. It was turned into office and storage space.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it amazes me that Epcot Central did that, that the fact that Horizons, tape and audio wasn’t, you know, handled inside the pavilion itself at first. I mean, cause I remember seeing, there was an old show Backstage Magic where you would go back and they, you would go inside the ComuniCore and see all those computers.

It was a show, so you didn’t really get to go close. And I didn’t even realize at the time that it was, it was that involved. So speaking of technology, I know we want to kind of finish up here, but I wanted to ask a few things more about other things you’ve done. So you guys, you know, at Alcorn McBride, you do a lot of work on different technological elements, audio, video, show control. This is a very big question, but what are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen beyond just technology changing in terms of how you do things at, at your company?

Steve Alcorn: Well, there’s a much closer relationship between vendors like us now and the theme parks than ever existed. Back in the day when the people at Imagineering were just buying parts and they were doing all of the engineering and design themselves.

This is particularly true with Universal Studios, where they design the attraction and the story and do the creative part themselves, but then they rely upon outside companies to fabricate the cabinets, to do the installation, to do a lot of the technical test and adjust work, and they specify our equipment to be used.

So we’re working with the installers and builders who build that stuff. For the theme parks, but our equipment is being designed specifically for our end user customers. So that closeness of relationship allows us to get constant feedback about what the criteria are that the equipment is to perform to things about vibration and about ability to source a whole bunch of audio or a bunch of video, and the ways that it can be controlled and synchronized so that we can synchronize audio on a vehicle with wayside audio within a few milliseconds, for example, or maybe even better than that.

Those sorts of criteria aren’t things that off the shelf equipment from a major company like a Sony or a Panasonic could possibly do. And so we’re able to do that because we can just focus on the engineering task of creating this equipment using 35 years worth of electronics advances. So we’re working with thousand pin ball grid array, uh, field programmable gator arrays and so on that are stuff that. aerospace companies would use to, to make space vehicles or something out of, and that allows the theme parks to then concentrate on what they do best, which is the storytelling part of it, the intellectual property part that ties into their movies and other material. And I think that that relationship works really, really well.

And I even think that a lot of the companies like Disney have moved more in this direction as they’ve found more companies on the outside that they can rely upon to the piece to do the pieces that are not necessarily the most effective use of their time. So that’s the big change I’ve seen over the last 20 years really is that sort of partnership in order to achieve an end product.

Dan Heaton: That’s good to hear because that’s more efficient, I think that leads to better attractions because people are able to focus on what they do best. And I know we’ve seen, you know, a lot of new attractions coming out. There’s definitely more of an emphasis on using video screens or not, I wouldn’t even say video, but screens like you see combinations like Transformers or Spider-Man, or things like Soarin’ or The Simpsons. How challenging is that? Because you know how fast green resolution and technology is changing. Is that challenging to make sure you’re out in front of that as much as you can when you’re working in that realm?

Steve Alcorn: Well it is, and the way that we’ve addressed that is the theme parks want absolutely perfect video quality, for example, on all those big screens. And we know one thing that is certain is that if you compress video in any way, the quality is damaged. You see these artifacts when you have a scratch on your DVD player or something, or if there’s an Internet dropout. When you’re streaming video, you see what happens. Well, that’s not satisfactory for theme parks, and so we make equipment that stores the video in completely uncompressed form.

You can’t get any better picture. Because we’re storing every single pixel at very high color densities. The thing is that every year, the projector companies come out with higher and higher resolution projectors or ways of seeming together so that you can’t see the seams by putting multiple projectors next to each other, and so there is no consumer equipment available that will source video uncompressed at those sorts of resolutions, especially when they keep doubling it or stacking projectors next to each other.

So we have the advantage that because we can synchronize things down to the pixel level, we make equipment that reproduces a certain resolution, and then if you need more, you just add more cards and they just stack next to each other and they stack above one another and you can build an image as large as you need it. So there isn’t really any practical limit as far as we’re concerned. As far as how big or how high resolution that image can be, so you’re already seeing in theme parks resolutions that are at least twice as good as what you’d ever see in a neighborhood cineplex, and they’re going even farther beyond that.

Doesn’t matter how big the screen is or what the resolution, we can just provide more gear and they can stack it and synchronize it. We take the same approach with audio and it’s all the secret really all comes down to the control and synchronization. That’s what is so specialized to our field and so that’s how we keep up with them.

And whatever crazy ride system they plan to come up with in the future, we think we can probably adapt to it because we can keep up with their audio needs, we can keep up with the video needs, and we can keep up with the control needs and. We can’t be shaken apart. They test our gear on shaker tables to make sure that it can withstand, uh, a year of torment on a roller coaster or whatever. So we’re pretty much there, ready for whatever they need to throw at us.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s great to hear because you know, the, the technology’s moving so fast. The fact that you’re able to adapt and adjust is, is really cool. And I know that some people might be listening at all the things you’re talking about and thinking while they’d love to get into Imagineering or engineering or a lot of the different fields, and I know you’ve taught a class, you know, for a long time about Imagineering and so when you’re doing something like a class like that, how do you find a way to summarize? I mean, like even in your book on theme park design, you kind of go through all the steps and there are a lot of steps to creating an attraction. How do you go about kind of summarizing that in a way that people can understand?

Steve Alcorn: Well, the basic text that we follow in Imagineering class is the text of that book, Theme Park Design. So people that are interested in getting involved in the technical side of things should start with that book. And then if they’re really serious, they should consider taking the class, which is at imagineeringclass.com and the class. steps you through with both videos that are, frankly, a lot of them are war stories and fun stuff to listen to.

But then also that text that tells you about the technical side of things. Then the real big value of it is that there’s a discussion area and you’re encouraged to create your own attraction from the brainstorming stage all the way through all of the technical stages, the test and adjust period and so on and to really live the experience of opening your own attraction. That discussion area is populated by me and by a lot of former students, many of whom are in the industry now. And so it’s a good way to get some exposure to people in the industry and to get some feedback from people that have done it many times before.

There’s quite a few success stories from people who have taken that class. Joe Fox this year won the Distinguished Service Award from the Themed Entertainment Association, which is our major, trade association for theme parks, and he started his career in Imagineering class.

Dan Heaton: Well, that, that sounds like a really exciting class, especially if someone’s either in college or earlier or, you know, and is interested in this field. So that, so that’s great. Steve, I really appreciate you being on this show. I feel like we just scratched the surface. I’d love to have you back on some time down the road to talk about other projects you’ve worked on.

Steve Alcorn: Sure, I’d be happy to. There’s always an unlimited supply of war stories.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. I feel like we covered about 1%, but if my listeners want to know more about Alcorn McBride or check out any of your books or your class, where’s the best place for them to go online?

Steve Alcorn: Well, to check out what Alcorn McBride has to offer, just go to alcorn.com., and if you’re interested in the class, the best place is to go to imagineeringclass.com. If you’d just like to check out the books, they’re available on amazon.com. As you mentioned before, Building a Better Mouse is the war stories about Epcot, and there’s a 30th anniversary edition of that book that is the best one to get because it has some photos in it that are not in the first edition. Theme Park Design is the book, the only book that I know of that’s really an engineer’s viewpoint on how to put together a theme park.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, and I’ll give a strong plug to both. With Building a Better Mouse, the original one I think I’ve read through multiple times and I recently read Theme Park Design. For me who feels like I do know a decent amount, there’s still a lot in there that I wasn’t aware of, so I really enjoy both books and highly recommend them. Steve, thanks so much again for being on the show.

Steve Alcorn: Thank you. It’s been my pleasure.

Dan Heaton: It was really fun to get the chance to hear from Steve Alcorn about his experiences in more than 30 years in the theme parks, especially at Epcot Center, but just in general, given all of his time that he spent working on so many cool parks and attractions.

I also wanted to mention that this episode is being released right before Mother’s Day, so I wanted to give a Happy Mother’s Day out to all the moms out there, including my own mom, and of course to the great Erin Heaton, my wife, who designed the website, does many of the photos that you see on the blog, and of course is a great mom.

She makes all of this possible. Happy Mother’s Day, Erin, and if you’d like to see her great design, you can go to tomorrowsociety.com. You can sign up for my email list and check out all the cool articles and photos. You can also follow me on Twitter at tomorrowsoc, or Facebook or Instagram at Tomorrow Society.

The Tomorrow Society Podcast is hosted, produced, and edited by Dan Heaton. The music for this podcast is written by Adam Hucke and performed by the Sophisticated Babies. Also, if you like this podcast, of course you can subscribe on Apple Podcast, Stitcher, or your preferred podcast provider. And don’t forget, while you’re there to leave a rating or review, they make me so happy and they also help the show out in ways you can barely imagine. Thank you so much for listening, and we’ll talk again very soon.

Leave a Reply