Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Following the massive opening of EPCOT Center in 1982, the transition to a new crop of Imagineers took hold at Disney. This shift led to a more ambitious park with Disneyland Paris in 1992. Show producers like Jeff Burke and Tom K. Morris helped enhance the typical theme park land. This was also true about Discoveryland, a different approach to Tomorrowland. Led by Tim Delaney, this ambitious land feels original yet still works inside the overall park.

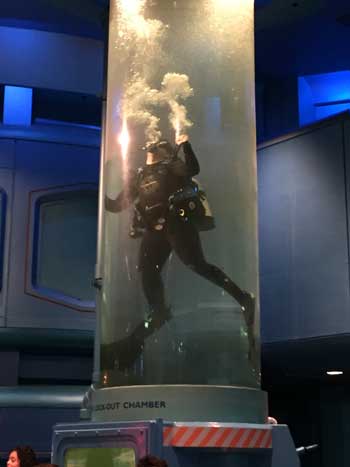

Delaney is my guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast to talk about his 34-year career at Disney. He started in the graphics department in 1976 and quickly moved to Imagineering during EPCOT Center’s creation. Delaney’s work on that park includes the design of The Living Seas, which was an epic pavilion for 1986. He describes that attraction plus the idea for the Hydrolators. I have clear memories of first visiting The Living Seas in 1986 and enjoying the full experience.

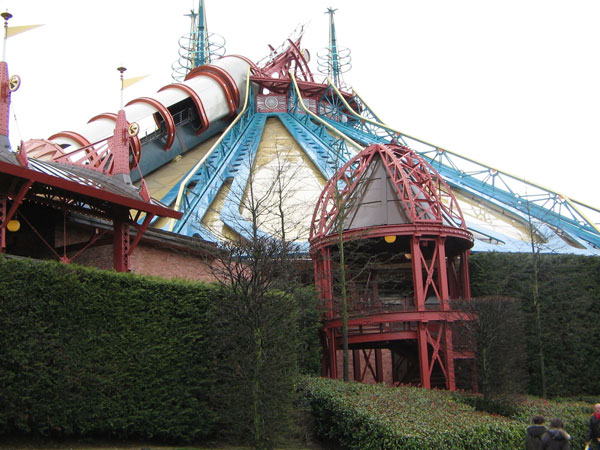

We also discuss Delaney’s concepts for the unbuilt Space Pavilion at Epcot and several possible designs. His interest in futuristic ideas goes back to watching early Disneyland TV episodes like “Man in Space”. This passion is evident in Discoveryland, which takes inspiration from masters like Jules Verne, Leonardo Da Vinci, and H.G. Wells. Delaney offers great details about designing Space Mountain in Paris and the evolution of that major project. The stunning attraction opened a few years after the resort and saved Disneyland Paris.

I really enjoyed having the chance to speak with Delaney and learn more about his amazing work. During his tenure at Imagineering, he worked on so many iconic attractions as the resorts expanded rapidly under Michael Eisner. Delaney currently manages his own company and continues to design projects around the world.

Show Notes: Tim Delaney

Watch the BBC documentary Shoot for the Moon on YouTube, which features Delaney and Space Mountain in Paris.

Support the podcast by making a one-time contribution and buy me a Dole Whip!

Transcript

Dan Heaton: Today on the podcast, we’re discovering the land of tomorrow with former Disney Imagineer Tim Delaney. You’re listening to The Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on Episode 79 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. Back in the spring of 2006, my wife and I took a trip to London and Paris and at the very end we did a day at Disneyland Paris, and I didn’t know that much about it. The Internet material on the park was not what it is now, so I went in mostly cold and was just blown away by the park. I wish we could have spent more time there.

It had incredible versions of Big Thunder Mountain Railroad and Phantom Manor and Pirates of the Caribbean, and especially of Space Mountain and Discoveryland on the whole, which just was the next evolution of Tomorrowland. And it looked so different and futuristic, but also kind of other otherworldly and Space Mountain especially was a highlight for me.

It was Mission Two, but still that launch into space rather than the slow lift chain and then all the effects and the speed of it. I came off of it thinking how fast were we going? We were going 70 miles an hour the whole time, which wasn’t really true, but it is very quick. But the fact that it was so beyond what I’d experienced at Space Mountain and in that whole land was something really amazing.

That’s one reason that I’m so excited about today’s guest who is a former Disney Imagineer. Tim Delaney, who was the show producer for Discovery Land at Disneyland Paris, including Space Mountain, which was added several years after the original land in Paris. I also love Tim’s perspective where he talks about being so interested in the Man in Space shows in the 1950s and then getting involved in Epcot Center through the Living Seas and just having that futuristic and interest in space that I have.

That was one of the things that drove me to start this site in the first place. Tim also has a great perspective from working at Walt Disney Imagineering for 34 years through multiple different eras of the company, including before Michael Eisner during that era, and then in the early days of Bob Iger. So he’s seen a lot during his time at Disney and still now is doing his own company as continuing to do theme design and work on a lot of cool projects. So it was awesome to get the chance to talk with Tim about his career and some of his thoughts on the theme park industry.

This was one of my favorite interviews I’ve done in a while. Tim just has a really interesting perspective and was so open to just talk about his projects. It had some great details that I didn’t know about attractions that I’ve loved for a long time. So let’s go talk to Tim Delaney.

(music)

Dan Heaton: All right. My guest today was a creative executive and director at Walt Disney Imagineering, whose work included the original Living Seas Pavilion and more at Epcot Center. He led the design of Discoveryland at Disneyland Paris and also worked in Hong Kong and on DCA, he received a Ray Bradbury Award for a lifetime of creative excellence in 2002. It’s Tim Delaney. Tim, thank you so much for talking with me on the podcast.

Tim Delaney: Well, Dan, it’s a pleasure to be here. I really enjoy these kinds of discussions and look forward to talking a little bit more about the Disney Company.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I mean, it’s always fun, especially given some of the projects you’ve worked on, which are some of my favorite things they’ve done. But I want to go back to the beginning. I know I believe you grew up in Glendale, California, which is interesting. How did you get interested in Disney and in theme parks when you were younger?

Tim Delaney: Well, let me just first talk about what really made me most interested in Disney. At the time, I didn’t make the connection between working for Disney or not, but what happened is when I was very young, you can go back and look whatever the time frame it was, but I was probably six or seven years old and I was addicted to the Disneyland television show to see Uncle Walt come out.

Well, it used to be Wednesday night, then Sunday nights. But the one thing that I realized very quickly is that I was really most interested in the Tomorrowland segments they would do. Each night it was from each one of the lands. It’d be from Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland or Tomorrowland. I was always really interested in the Tomorrowland, even at a very, very young age. And most specifically what kicked that off was the “Man in Space” program that Walt did with Ward Kimball producing.

There were three shows, three television shows, and they’re very famous when you look back at them now. But there was “Man in Space”, “Man in the Moon” and “Mars and Beyond” the three television shows. I remember seeing them, and I was completely fascinated by this and on many levels because basically I didn’t know anything about it. This is in the early fifties, right?

I saw these television shows and here was this imagery that Ward Kim, who I met and worked with years later that Ward Kimball had put together that for some reason Walt Disney wanted him to produce the show. But the shows were a combination of real science with Werner Von Braun and Willie Ley talking about space travel and our travel to moon. And again, we had no space program in the United States. So these guys put these images and these ideas together.

Then there was kind of the wacky Ward Kimball animated aliens and things like that. They did a whole animated section of, for the first one man in space about a launch into outer space, which I do believe that that big rocket with the space vehicle on top was the right way to go versus the space shuttle, but that’s a whole other discussion. Anyway, so there were these three shows and the second show had actually been more realistic. They had shot real characters or real actors in a whole outer space scene. It was the first time I had seen something that wasn’t outer space, it was really bad or aliens or horrible monsters. It was really science fact. Even at that time, I’ve said this before on some of the occasions where I literally talked, I turned to my parents, I go, is this real?

I think my mother said something like, well, Mr. Disney just made all this up. I was completely amazed that a television program could talk about something that had never ever happened before, but had created a vision. This is a big theme for me now, it has been, and it will be for the rest of my life. Somebody created a vision that suddenly other people looked at and was completely amazed by.

So the story goes that President Eisenhower at the time after the shows called Walt and said, I’ve got a bunch of scientists. We’re trying to get into space travel. Your shows gave us a path. Can you send those shows? So Walt send all those shows to wherever they were doing all their space programs. But I want to emphasize this really importantly, and that is that the concept of creating a dream, creating a vision for people, so you see a path is the way to get things done.

It was the basis of everything I did when I worked in Imagineering. Fortunately for me, I had the ability to draw and paint and create ideas and show those ideas, which was a huge benefit for me. And plus obviously working with great teams. But the idea of being able to create a vision, and you can do it by writing, sketching in any way, it’s a very, very valuable asset when you want to be in the idea business. That’s basically where I went and where I started. I was always a big fan of Disneyland, but I never had this dream of working for Disney, not until years later when I had the opportunity to do so.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, well, those TV programs, I’m very interested in the space program more looking back at Apollo and everything, but those TV programs are fascinating now. I watched them now and I still think, wow, and it’s something where you think by now they might seem quaint, but they were stunning and I imagine had a really big impact, especially on a lot of kids, which may have led probably to a lot of things that happened with the space program.

Now you had that excitement and were interested in had dreams like that. You mentioned that it took a while to end up to get to Disney. But did you, with your education then focus on design and on things that would ultimately lead you to Disney? Was that a plan going forward?

Tim Delaney: No, actually I think it was more that overall the specific target of Disney was not where I was when I was in college. I was more specific into using my artistic skills to actually create this theme of creating images and creating visions of something mostly in my case through artwork. That’s what I like doing. I always, for some reason, I kept gravitating to these kind of robotic things and spaceship things, and I did all these outer space paintings and I mean, I just did a lot of stuff.

Actually, I was also very fortunate. My parents kind of indulged me and my brother and I used to share a bedroom, and I used to get these big pieces of chalk and I would draw these huge drawings on the side of my bedroom wall, mostly of hot rods and cars and all that. But I did discover very quickly once I got out of high school, never in high school, but that I had this ability to draw.

Then I went in that direction, and then I eventually ended up going to Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles here. When I arrived there, I felt like, oh my God, I finally found my home and I really just dove in. Art Center is one of the toughest design schools anywhere, and you work your tail off and I learned how to draw and paint. I mean, the only way to measure yourself is to see what you are against your other fellow students. I ended up doing pretty well, and I loved every second of it.

So once I graduated from Art Center College of Design, three years after I was out of school, one of my instructors called me, and I still to this day, I don’t know why he called me, but he called me and said, Hey, I’m working at WED Enterprises. Would you be interested in job here? And I go, what is WED Enterprises? He goes, well, we’re the division of the Walt Disney Company, Walt’s personal design company that he created to build the Disney theme parks.

I was like, at the time I was in another business and I said, no. And then six months later I called them and said, I’d love to work with you. And they said no. Then six months after that, it took about a year. Then we both got together and then I started working at WED Enterprises on June 1st, 1976. The funniest thing is that when I first went over there, I couldn’t find the building. I don’t know if people know, but Imagineering is, you cannot get into, and it’s an enormous, today, it’s an enormous complex of buildings that nothing says Disney on them, it says Creative Campus.

Now, when I was there, it was just one or two buildings, but once I stepped in there, it was stepping in for me to Art Center when I said, oh my God, this was all dedicated to theme parks to, and I love Disneyland, all the talent that was there. They had a model shop. They had these great artists.

And I will tell you that when the day I started, I spent every second either working in my, what I did is I started, I was hired by the graphics department to do all their illustrations, and in the graphics department, they do a lot of signage and things like that. So we did a lot of corporate things. If somebody wanted, some corporation wanted to sponsor a store on Main Street, then you would do the illustration of the store, and it could be like when Sunkist came in on Main Street at Disneyland.

So you do all the illustrations, you show the signage and all that. I did that for almost a year. But I will tell you that I spent every second I had when I was there during breaks and during lunchtime, I would go over and I met everybody. I walked into everybody’s office offices, I introduced myself. And I saw what was going on at MAPO. I saw things that just things that people will never ever see. I mean technologies that they were developing, and I was just like, I was addicted. It was just fantastic. On top of that, they were actually paying me every week. So that was really great.

Dan Heaton: You were fairly young when you joined, but that time in ‘76 there were so many of your famous Imagineer names like your Herb Ryman and Claude Coats and Marty Sklar. When you’re coming in and you’re so passionate about it, what was it like to work with so many of, now we consider legends, but people that were so experienced at the time?

Tim Delaney: It was the greatest experience of my life because as you say, these were the Disney legends. But at the time, there was another opportunity I had that was quite extraordinary, and that is that, see, I started in ‘76 and I gave a million stories. I could tell you as I told you, I would go around and introduce myself to people, and I met Herbie and Marc Davis and Claude Coats and Walt Peregoy and X Atencio, and I mean, it was like the who’s who of all those guys, the guys in the Model Shop. It was phenomenal. These guys were the guys who actually worked well, and it was fantastic.

The other thing, and I’m going to come back, it sounds like I’m going to get lost here, and I don’t mean to be, but I want to come back again. I’m going to tell you that when I did do all this, introducing myself to people and talking to ’em and seeing their work and finding out about what Herbie did and all that, I went home because I had a particular portfolio now seeing what they were doing, and I had hearing the rumors that this EPCOT project was being built.

So Marty was running meetings with Ray Bradbury and John Decuir Jr. And all these people, and I kept thinking, you know what? I really think I could do something for this company. And a lot of the guys, you take guys who are wonderful, amazing artists like Herbie and Sam McKim and all these guys, the extraordinary thing about them is that they were brilliant artists, but a lot of ’em didn’t do futuristic stuff.

So for a year from the second I started for a year, I went home every night and worked on a new portfolio, and I did these renderings and I did these drawings and I did spaceships and I did contemporary architecture. I did all of this stuff. And after a year, I went to the guy who had hired me and I said, I really think I can add a little bit more to this company, and I know the company’s going and doing EPCOT, which is more the EPCOT experimental prototype community of tomorrow.

I said, I think I could do something. And he was like, okay. I told him, I said, I’m going to set up meetings with John Hench and Marty and I want to show my stuff. So I did that, and I remember showing John Hench and Marty Sklar in Edie’s conference room, and I was going through this whole all these drawings, and they looked at, Marty looked at me and he goes, don’t you already work here?

I said, yeah, I do, I do. But I said, I think you guys are going to do this contemporary futuristic work, and I think I could help. I’ll just leave it at that. So I went back to my office and I had been doing a whole bunch of different work in the graphics department, but I also did a whole series of paintings for Space Mountain because we opened Space Mountain in Disneyland in 1977.

So I went on vacation, came back, and my boss calls me in his office and he goes, oh, I don’t have enough work for you. I’m going to have to let you go. I said, okay. I went over to my office, pulled all the posters off, went into John D.’s office and said, I’ve just been let go, but I think I can help you. And he goes, I don’t know if I can help you, and I don’t know. So they gave me two-week severance pay.

At the end of a week, they called me back and moved me upstairs from the concept design department. My office was about 10 feet away from Herb Ryman’s, and I talked to Herbie every day for the next seven years, and Herbie would leave me these little drawings, and Herbie told me all about what it was like to work with Walt. Herbie came to our wedding, my wife and I’s wedding.

And it was just great. It was a great experience. It really was great. So now I’m going to tell you the other part. When they started EPCOT, not only did they have the guys working there, but they reached into Hollywood and they brought in all of these Hollywood art directors. Jack Martin Smith, who was the head art director at 20th Century Fox, Walter Tyler, who was the art director for Cecil B. De Mille, Bob Klatt. There were probably a couple of others.

These were meant to be the big art where they were going to back fill all the art direction design needed for these pavilions at Epcot Center, and they also used them and showcased the talent that they were using to really go out and enhance, to promote what EPCOT was going to be with the sponsors. So I’m working there, so one day I go, okay, Tim and I was 28 or 27 or 28, and they said, okay, well we’re going to send you with all the other art directors down to Florida, so you can look at Florida and you’re going to go down on Walt’s plane on The Mouse.

I went, oh, great. So I sat next to Walter Tyler and I said, Walter, I got to tell you when I was a kid, I went to every big motion picture in Hollywood, and I said, that scene in The 10 Commandments where Moses throws back the curtain and says, Pharaoh, I’m building your city, and the oils is lifted up. I said, Walter, how did you do that? And for the next five hours on that airplane, Walter told me every story about Hollywood and working with Cecil B. Demille and all that. It was like, okay, this is great.

The other thing I did want to mention is, and this happened years later, I became very, very close with Ray Bradbury and from about 1980, I’m going to say about 1987 until he passed in 2009, I guess. So for those 24 years, about every four to six weeks, I would go visit Ray and sit and talk with him. And I’d spent an hour with him and I spent almost 24 years just talking with Ray Bradbury. One conversation with Ray, and we’d meet in Paris and he was a lovely guy, and when his wife was alive and my wife, we’d have dinner in Paris at the Jules Verne restaurant. It was magic as far as I’m concerned. Again, I’m not even talking about the projects, I’m just talking about the extraordinary people that I had the opportunity to meet.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I can imagine Ray Bradbury, I still need to learn more about him, but also his contributions to EPCOT. It’s so interesting that he was involved with Spaceship Earth and with that script and so many of the concepts that they went to him and so many others, it fascinates me that whole production with Epcot and what they were trying, like you mentioned with all the art directors, they were doing so many interesting things there. It was crazy. I mean, it got so busy too. What was the atmosphere like as EPCOT kind of ramped up? I know you were closely involved there at that time. What was Disney like when Card Walker was leading, but just with them trying to build this park that was like nothing that had been done before?

Tim Delaney: It was very exciting. It was completely insane because there was nothing ever done. Like what? Actually, to tell you the truth, I believe even looking back on it now, I think it was completely insane that we did what we did build those major pavilions and invented new ride systems. The idea of just putting a ride inside that ball for Spaceship Earth, I mean from an engineering point of view is completely insane. I mean, it really is.

But you know what happened is no one knew. You didn’t even imagine that we were doing something that was impossible. So the old Walt thing, I like doing the impossible. It’s fun to do. We didn’t have any idea what we were doing. There were the essence of we can get it done, and we did get it done. I mean, thank God. And the Living Seas Pavilion was really complex, and that didn’t come till later.

We did have of course corporate sponsorship, but it was really an extraordinary event and it was somewhat challenging only because the company really was getting into things that they didn’t know and they ended up running over budget, and that hurt the company in the long run. Well, actually I take that back. It hurt the company initially, but in the long run it saved the company. It brought in the new administration, which changed everything.

Now you just mentioned something about not knowing enough about Ray Bradbury. I have a video if I can send it to you, and it’s video of Ray went down probably in 1977. Marty had invited him to Florida Ray Bradbury. I don’t know if you know that Ray Bradbury never drove a car and he really was always afraid to fly. And the reason is because he witnessed a car accident.

He was very young, and so he never drove, they finally him to fly down to Florida. So he flew down there and he was the guest speaker. He gave a speech to the business leaders and potential corporate sponsors, and he talked about what EPCOT was going to be. I just looked at it again not long ago, and the vitality and the energy behind this man and the creativity behind him is you’ll be stunned when you see it. It is so fantastic when I see it because I knew him all toward the end of his life and I could give you six hours just on Ray Bradbury.

One of the reasons I did like to speak with him is that he was really not only a great fantasy and science fiction writer, but he was also a great city planner. So he was always on the case of Los Angeles about trying to promote mass transit. But yeah, those were the days, I mean, those were really exciting days. It was really challenging and we were hiring, they were hiring people. They hired up for a lot of people, a lot of disciplines. It really got, it was amazing. A lot of people who became the people working on most of the projects throughout the next, I would say 25 to 30 years, all cut their teeth and got started on EPCOT.

Dan Heaton: That working on all those new technologies like you mentioned in new ride systems while probably crazy at the time, a lot of people were able to test their skills and show what they could do. So I think that was probably really positive there. You mentioned The Living Seas, and I know that didn’t open right away, but I definitely want to learn more about that. So that one went through a lot of changes over time. I know from the start to what we actually saw. What was it like to work on that project and then ultimately move it forward?

Tim Delaney: Well, the best thing about that project, once again on projects like that, the best thing, the best opportunity and the most memories you get are the people you work with. The first group we worked with is that we brought in advisory, an advisory board to come in and give, consult all the EPCOT pavilions all had advisory boards. They would get the icons of that particular subject, whether it was in transportation or communication or in this case obviously people who worked in the oceans. And so we had Dr. Bob Ballard and I had been working, I met Bob 35 years ago and he was on our board. I’ve worked with Bob, I’ve been working with Bob for 35 years afterwards.

Bob is the one who found the Titanic in 1986, worked with Dr. Sylvia Earl. We worked with all the National Geographic people. So it got started that way because we wanted to tell a story in the Living Seas, which it was going to be unique in a sense that it wasn’t aquarium, it was not meant to be talking about marine sciences or it wasn’t meant to be another aquarium.

It was meant to be our living and lifestyles connected to living in the oceans and participate in this vast ocean that covers 70% of this planet. So that was a very interesting challenge, number one. Number two, from a story point of view, number two, the technological side, Kim Murphy, who was kind of leading up the kind of ocean sciences part of it, wanted to, his dream was to build this tank which was 200 feet in diameter and about 25 feet deep, and it was going to be the largest self-contained saltwater tank in the world. I mean it really was.

So he was handling all the fish that we brought in, and we made these dimensions such that when you were looking in the windows or looking out in the observation module, which was about 40% of the way into the tank, we wanted to make sure you didn’t see any walls.

We kind of art directed the whole thing with lighting and painting of the walls and coral reefs that would kind of hide distances. So we looked like, for all intents and purposes that you were in the ocean. Then the sea base actually talked about what man’s development, humankind, I should say it’s development in the oceans.

One of the things that I wanted to do is I wanted to make sure we kept pitching this whole thing that you were underwater all the time. So we had the lockout chamber, which was the tube in the middle of the divers would come in and then they would flood the tube and go out into the tank. It was really meant to be like a mission control underwater sea base. So the one big challenge is that we wanted to do is there’d been talk about creating what was called hydrolator.

So when I was given the task to design this whole thing, I went, okay, I love the idea of the hydrolator. The hydrolator is really meant to separate the world of EPCOT to your experience of going down under the sea. Most great attractions, Disney attractions, all have some kind of portal that take you from your normal world into this new world. So it was great, fantastic.

I’m like, great, how are we going to do it? And they go, I don’t know. That’s for you to figure out. So we started working on ideas, and the first one was really the things that we really built were you came into this chamber, you came into this hydrolator, and you looked out and you saw these walls of stone and there’s water inside. Then we would descend down. The interesting bit of irony is that the pavilion was eventually sponsored by United Technologies, which is the holding company that had Otis Elevator.

So we talked to their people and we realized after almost 10 minutes we couldn’t, there was nothing they could do for us because on one hand, when you work on real elevators, the intent is to make you feel like you’re not moving at all, just acceleration, vertical acceleration. What we want to do is we want to create a special effect that made you feel like you were descending down and really going someplace when in fact you weren’t going anywhere.

And I swear to God, I remember the first day we opened the pavilion to guests, we were just testing it, soft opening, and I thought, I’ll go in with this group of guests and see what they do. I’m sitting and looking at these people and they’re all just standing around going in an elevator and they all look like there are people going in an elevator.

And I thought they would all start laughing and well, this is ridiculous, this is dumb and all that. They were just like, okay, yeah, we went down 25 feet, we’re now under the ocean and doors open on the other side. And we went through and got on the ride and it was like I was completely shocked that people just bought that whole thing because we had spent years working on just the right physical movements and the visual movements and the lighting controls and all the clicks and clues and everything.

You could imagine that would actually create the sense that you were descending down and it worked. It’s what you expect from Disney that you’re going to do that extra thing, that you’re just not going to go through an open door like, oh yeah, we’re now under the ocean. No, you have to separate the people’s outside world to this new alien environment. And that’s what we wanted to do. It worked really, really well.

Dan Heaton: I was 10 years old. We went, I think in ‘86, and I totally bought that. We were moving, and I don’t think it was just because I was 10, because it took me a few other times, well longer to realize that I think, like you said, with Disney, you kind of go in and you’re in the right mindset, and plus you have that. You come in and there’s the pre-show movie and then it directs you to the hydrolators with the lighting and the whole experience. That’s where when eventually as the pavilion changed, there were steps of that that were removed. Like you said, it didn’t have the same impact because you need to go through every single step to get there.

That’s where I think the Seas did so well, even the Sea Cabs, it was so good because even though it was a short attraction, you were able to kind of have that transition from outside to the station. It really comes across super well. I think what you did was it made it work, and I appreciate that because without that, it’s not going to hold up. And I actually hear they’re doing a new space restaurant, I hear they’re going to do some sort of similar transition like the hydrolators to go up in space where you don’t really move. I think that’s great. It shows it could still work.

Tim Delaney: People expect that kind of care and thinking and that you put the money in to make the experience pay off. That’s a real valuable thing, and that’s ingrained in you, and you’re at Imagineering. Now, in the particular case of Living Seas building, the exit we didn’t have, we just ran out of money. So it was more of a closed door. Closed door, and there was some lighting effects, but we didn’t shake the floor and all that.

Now, I’m sure you’ve heard the, this may be anecdotal, I would love to get verification on this, but there was some woman who went to operations and complained that her son or daughter’s ears were popping as they descended down into the ocean, and she was complaining about it. So I don’t know what operations said to her, but we’re like, really? Okay. But it’s a fun story that we all we like to talk about. There is one other thing, actually, I’m going to tease you with this and we’ll talk about it a little bit more when we talk about Disneyland Paris, but just remind me about Kirk Douglas.

Dan Heaton: I’ll remember that, but I like the tease. That’s good. I mentioned the space restaurant, but I also wanted to ask you, before we even get to Paris, I want to ask you about, I’ve looked at some of your concept art that you have on your website, which is incredible. I know you worked on some concepts for a pavilion that really fascinates me, which is not the space pavilion that we have now, Mission Space, but the space pavilion that was planned much earlier that wasn’t built. So I’d love to hear about some of your work on that, the concepts for that and how that kind of came together.

Tim Delaney: Well, I worked on two concepts for a space pavilion, and one of ’em was, this was when I was, well, let me take half a step back. The part where I told you I came back to Imagineering after the two-week severance, and they brought me back a week later. At that point, I went to work for a gentleman by the name of John Decuir Jr. And his father was one of the most famous art directors in Hollywood. He was the art director for Cleopatra, and he was the art director for Hello Dolly.

He’s the only man in 20th Century Fox history that broke them twice for two movies. The Walt Disney Company brought in John De Cuir, the senior guy, and he was such an amazing talent, artistic talent, but an energy guy, I mean, if you ever saw one of his presentations, you’d have been blown away.

This guy starts out talking, he is got his suit on, and he is got his tie on, and by the end of the presentation, he’s got the tie ripped off, the shirt is open, he’s down on one knee. I mean, this guy knew how to sell. He could sell hand warmers in Africa. I mean, this guy was just amazing.

So what happened is that he had a concept, an idea for doing a space pavilion. What it was going to be was a big round ball. So I’m assuming you’re talking about the big ball building with the gantries all around it? Yeah, yeah, definitely. Okay, alright. So he had this idea, this is so funny. Now here’s the story I could spin off for whatever. So he had this idea that we was going to do, we were going to do this, if you can imagine a vertical ring, like circle vision, a ring, and then there’s two halves bolted to it.

So the audience was going to be in the two halves, and you would look at this entire space pavilion in a vertical ring that went 360 degrees around half. The company said, well, that’s never going to work. And the other half said, oh, it’s going to be a brilliant idea. So I get a call one time and say, look, be down at Disneyland at six o’clock in the morning.

Tomorrow we’re going to run a starfield in the CircleVision Theater, and we’re going to test this. So I’m like, sure, I just have to get to Disneyland by six o’clock in the morning. Go down there and all these people, there’s operations people, there’s creative people, and there’s Ron Miller who was the head of the company at the time, President of the company at the time, and John and just all of us. So what they asked us to do was, you remember the CircleVision Theater, right?

It has handrails. So they said, lay down on the handrails. This is the most uncomfortable thing in the world to do. And so now you’re laying down, imagine being horizontal, laying down on handrails, and I’m looking across, and Ron Miller is right across from me, and they start the projectors and they’re running a star field in there, and the star field would kind of rotate and move around. And so they ran that for about three or four minutes, and then people talk and then they run it again, and we take a look at it.

Then finally we left, and I will tell you something that really, it became kind of a symbol for me about how things work when you talk about ideas that have different opinions about how that work. And as I said to you, half the people thought this is going to work great, and the other half people thought, eh, this isn’t going to work at all.

So everybody walked out of that theater, convinced they were right. The people who thought this is never going to work was convinced it wasn’t going to work, and the people who were convinced that it was going to work were convinced that it was going to work. So I was like, I’m totally neutral on this thing. Doesn’t matter to me. But what they needed from me more than anything else is that they needed this rendering of this pavilion.

I’m going to backtrack just a little bit one more time really briefly. When I first came to work back and started working at EPCOT, I spent almost a year. All I did was draw every day eight to 10 hours a day. I did paintings, drawings, I did point-of-view sketches; I worked on every pavilion. And I worked on all of these things in real quick sketch, but I had this technique where I would do line drawings and then I would paint through them and all that, and you’ll see a lot of those.

I mean, I’ve got hundreds of those. Anyway, this one painting wasn’t going to be like that. This painting had to be a real sales pitch sales piece. This rendering is probably about, I saw it about 10 years ago. Again, I hadn’t seen it in years, but the painting must be 60 inches across. I used to paint everything really big because we didn’t have photographic capability of blowing things up.

So I did this painting and I remember getting it done around 11 o’clock or 11:30, and I turned it over on my desk and I went out to lunch, and then I was at the lunch. I get all these, I came back and there were all notes in my office, where’s the rendering? You said it was going to be done today. People were freaking out. So I just turned it over and said here, and they loved it.

They just flipped out over it. It was like, this is perfect. This was great. So it was one of those things where asking me to do a space thing, that was the easiest thing for me to do. I knew how to paint the gantries. I knew how to mean it was a crazy idea. But the building, I made it just really compelling. And so they liked it, and obviously they couldn’t get it to work. I don’t know what happened about who would sell it and whatever.

I worked on another idea for a space pavilion, which was going to be more of a space camp kind of thing. But there must’ve been seven or eight space pavilions done before Eddie and Susan Bonds did Mission Space and got that done. But there were a lot of ideas. I mean, a lot of, there was thousands of ideas ago floating around that company, and they never get wasted. They just may not be what they end up being at the time that you want them to be there, but they never throw anything away. They always end up using ’em for something else. But I don’t think anybody did the vertical CircleVision mount.

Dan Heaton: I always hear that basically there can be an idea that 15 years later, 20 years later, something completely different uses that ride system or that effect. It’s common I know.

Tim Delaney: Yeah, I know. It’s kind of good. It’s kind of like the ideas, they kind of fine wine. They have to mature, and you also, primarily, really what you need to do is you need to have the right theme, the right story, the right technology to make it all work. There’s a lot of ideas that just don’t get anywhere because the technology hasn’t been invented yet. You see this in motion pictures too. Look at the stop action animation versus digital. I mean, a lot of things couldn’t be made until the digital technology caught up with the concepts that people wanted to do, but that was what EPCOT was all about.

Dan Heaton: For sure. And speaking of that though, I want to move on to Paris because I visited Paris in 2006 and really was stunned by just almost every part of it, whether it’s Fantasyland or Frontierland or the castle. But Discoveryland in particular and Space Mountain really stood out to me, and I know you were leading to the design for that. So I’m curious, how did you get involved in working in Paris, and then ultimately, how did things go for Discoveryland?

Tim Delaney: So when the word went out, again, remember where the Walt Disney Company was coming from. When that new administration came with Michael Eisner and Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg and the whole a team of entertainment executives came in, we were thrilled. All of us who had been in the, we were thrilled. I’d been in the company since 1976, and they were coming in ‘84 and everything that they touched because the company had lacked as a vision, but the potential, look at Walt Disney World and the library and all that.

So this new administration came in, they just took the company’s real potential and it just took off. These guys were real pros. So they said, alright. Michael said, all right, so we’re going to open up. We’re going to expand these theme parks. We’re going to go to Europe and go to either Spain or Paris.

The second I heard that, bang, I was on it. I told Tony, I’m in, I’m on this. I’m totally committed, and I want to do whatever Tomorrowland you’re going to do. So he was like, great, fantastic. So he was like, I’m thrilled. I’m thrilled to have you. And I got Tom Morris and I had, who did he have? I think he had Jeff Burke and Chris Tietz at that time.

Eddie Sotto came in later, and Eddie ended up doing Main Street and Eddie, each one of the producers were really terrific, and it was a real pleasure to work with all these guys. I mean, I had Eddie Sotto on Main Street, and I had Tom Morris for Fantasyland and that, so they flanked me, and I was in between. So I was really excited and we did all of our research trips and it was terrific.

But we began talking about the problem is all these Tomorrowlands all end up becoming yesterday lands, they date themselves. So when you work on projects like this, and this is one thing I have not mentioned yet, but I will bend over backwards to mention this, is that no one does these projects by themselves. I mean, I did a lot of renderings of concepts, but that’s just me drawing stuff.

But when it comes to real projects with the Living Seas pavilion or Disneyland Paris or Euro Disneyland as it was called that time, you start assembling creative people and designers, and then the projects expand as you go and you begin adding more of the disciplines. You begin landscaping, lighting. The magic of Imagineering is you have the best people in the world in any discipline, you want lighting people, you get the best people. You just pick and choose what you want.

And usually teams kind of stay together, but a lot of times they vary. So I was in on the first group and we took tours of Europe and looked around and said what was going on? But the one thing, this whole issue of the theming of what a Tomorrowland would be, and I think Tony Baxter was kind of very helpful in this, but said, you know what? We need to make something that’s more focused on what European visionaries would be. Let’s just do something like that.

So one of the things that I did when I started getting into design, I started analyzing the other lands. And when you look at Fantasyland, you see a little bit of Pinocchio, which is German, or you see a little bit of French, which is the castle, or you see a variety of stories in a variety of cultures being told.

And you look at Adventureland. Adventureland is really about exotic ports. There’s North African, there’s South Sea, as I said, exotic ports from around the world. Then you look at Frontierland, there’s the Southwest, and then there’s the Northwest, and there’s Big Thunder and the Arizona, Arizona kind of theme of the Old West and all that.

So each land ends up being a collection. It isn’t just one, but yet Tomorrowlands were always one architecture, and after working on EPCOT, you realize we can’t do this anymore. So I decided I think this theme of great European visionaries is a good idea. We have Jules Verne and Leonardo da Vinci, and people who really kind of in the Western culture really have led what visions and engineering is all about, which is the overall theme for what a tomorrow end would be. But I decided, why do one future?

Let’s do a variety of future. So we had a Jules Verne future. We had the Orbitron, which is kind of a planetary orbital model of a Leonardo Da Vinci kind of thing. Then we had a time machine, and then I also had a George Lucas future. Then if you want to say we had a Captain Eo Michael Jackson future, we did too. But then we also did the Autopia.

That was kind of meant to be the 1930s in a way, “Magic Highway”, the other futuristic TV show that Walt had, which was highways across the country. It was that kind of 1930s deco kind of thing. So we just took these themes and started working with them. One of the reasons why I really did want to develop the Orbitron is that one of the other problems, now, the greatest solution to all this thing was the Tomorrowland and Disneyland.

But the Tomorrowlands since then had all been, when you think about the big buildings, you have all these big buildings. You have Star Tours and Space Mountain, you have all of these big mega attractions, which are very popular with people. The problem happens to be there’s no animation in them. The buildings all hide them and are stagnant.

So I said, look, I sent you that photograph of myself in the Rocket Jets at Disneyland. And I said, okay. they go, well, many times what they do is that they assign you programs. You have to put this attraction in and that attraction and to do all these at attractions. So I said, well, I’m not going to do, there’s no way I’m doing just another rocket ride, so it’s got to be something else. So the short version is I had a great guy who helped in the design, did all the most spectacular drawings of that Orbitron in Paris, which is the one at Disneyland also.

I mean, this thing is, it functions on three levels. It’s an icon, it’s an animated piece of sculpture, and it’s a ride. It’s a trifecta of what you want for rides to be outdoor rides. And with the exception of maybe Dumbo, people had never really kind of restyled iron rides before. So this was another one. They did the Astro Orbiter in Florida, and I did another version in Hong Kong.

So what it does is it creates animation in the land. You want to see things moving. Now, if you remember Disneyland, you may not remember Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, but what I loved about that is that they had the Rocket Jets on top of the Wedway building, which was way up in the sky. You had the Skyway, you had the Submarines going, you had Autopia. You had actually, even beginning with the Phantom Boats, Tomorrowland was a land on the move, and we had gotten away from that.

They’d gotten away from all these things. So I needed all this animation going on. The other thing is we made a conscious effort for Disneyland Paris, and all the producers, we would have all these discussions talk about this stuff with Tony and Tom and Eddie and Jeff Burke and Chris. And because we were going into a culture was the first time we’re going into a culture that, well, I should say it the second time, sorry, after Tokyo.

But it was going into a culture that we really didn’t want to have words trying to describe things. So we put more emphasis on the Castle, pirate boats, the Orbitron, the Hyperion Airship had Star Wars. I had an X-Wing fighter sitting on its edge. We eventually ended up building the Nautilus submarine we built. I couldn’t necessarily get all these things moving, but I actually got these icons, these devices for traveling either in the outer space or under the sea or across the land. So the whole park was done that way.

The Skull Rock and Adventureland was beautifully done with a pirate boat. So you don’t really have to explain it. People, all cultures go this. You don’t have to say, oh, that’s a pirate boat. That’s where pirate sits. No, you get it. So there was a conscious effort to do that, and I think that that’s one of the reasons why Disneyland Paris ended up being such a beautiful, beautiful park. I mean, it’s beautifully finished. It really came alive, and we really loved all that.

Dan Heaton: I think that’s a great point because you think about just, I mean, all Disney parks have some kind of icon, but I felt like you mentioned almost each land had that, and it was even more stunning and stood out, like Space Mountain, for example, which you worked on where Space Mountain’s always a stunning icon, but rather than doing, again, the white structure and such, it’s looks like it’s some sort of crazy Jules Verne type inspired building, but without seeming, it’s just copying. It’s its own thing, and it’s a stunning piece of art. Like you said, you can just look at that and say, that’s incredible looking. Oh, yeah, there’s a roller coaster inside that loops and launches. It’s like a bonus basically.

Tim Delaney: To that point about Space Mountain, Euro Disneyland opened in 1992, and so that Space Mountain opened in 1995, like all the Space Mountains, they were never there on opening days, but it ended up working great as far as I was concerned. It was a secondary project, which kind of recharged all of Euro Disneyland, if you remember. It started out great attendance wise, and then they were having problems with the stock and people weren’t going to the hotels.

So the attendance went down and Eisner was threatening to close the park, and it was really not a good time there. But I’m going to come back to that, but I’m going to talk about the Space Mountain. The way it turned out, the way it did, there was originally a very large Space Mountain that was going to be put in there. It was 300, it was a hundred meters in diameter, and it was going to have the Nautilus inside.

The ride was going to be inside, and it was basically a whole world inside this huge mountain. But because Euro Disneyland wasn’t performing as well, they just said, we can’t afford this, so you’re just going to have to put a Space Mountain in there. Now, I started working on Space Mountain at Disneyland in 1976. These are the small ones now, the Walt Disney World, that’s 300 feet in diameter.

And that is an absolutely beautiful building, I think. I mean, it’s just the scale and proportion of the size is magnificent, and it basically has two ride systems inside. It’s enormous in inside. I started working on, I did the arcade down at Disneyland. I mean, most of the building was all finished. By the time I came to work on the project, I have to say, after years, and this does not make me popular with people at all, but I’m just going to tell you that right now.

So after a number of years, I kind of said, if I’m going to space, I don’t want to go up these three lifts, clickity, clickity, click clickity, clickity, click, then up the main lift, then up another one, and then the ride takes you up and it’s just like a regular roller coaster. And I said, what would you like to do? I mean, I said, here’s what I want.

If I’m going to go to outer space, I want to get shot to outer space, launched in outer space. So we started working on this thing, and there was a ride system called Montezuma’s Revenge, which was down at Knott’s Berry Farm, and it was a cable driven system, which was just a sole 24-passenger train. It gets launched horizontally, goes into a loop, and then the loop runs out, and then the train kind of runs its energy out, then comes back, goes through the loop backwards and back into the station.

It was done. And I loved the catapult launch. I loved it. It was like in terms of physical, well, I don’t want to say stress, but physical movement on human beings, acceleration is the most exciting. You don’t feel like you’re falling, you’re not spinning, you’re not acceleration. Being pushed back on the seat is really the most exciting thing.

So I said, why don’t we just create, believe me, if they can launch a 24-passenger train, goes into a loop and then runs its energy out on a track that just extends up a hundred feet. Certainly it can launch to the top of a Space Mountain building and then just become that’s on a system. So we started working on that, and it was great because what happened is we said, from a story point of view, we wanted to a Jules Verne-themed ride in his book From the Earth to the Moon, which he wrote in 1865.

It was about a rocket that was shot to the moon. I mean, it was interpreted by Lumiere with the rocket into the eye, but that was different than Jules Verne story From the Earth to the Moon. And then said, fine, we’re going to fire this thing. What we’re going to do for the first time, we’re going to do three loops in the dark. By the way, the ride goes twice as fast as any other Space Mountain.

So we started working on this thing, and what happened is we got Vekoma to do all this, the ride track, they built the track. But our engineers in Imagineering actually developed the catapult launch system, and it was the first catapult launch coaster ever. I mean, today you think catapult launches are everywhere. So it was the first one. And then the other one is Tom Morris had always been working on this idea of using a little Walkman to play music on the ride.

So we said, well, let’s incorporate onboard audio, which was done the first time ever on Space Mountain in Paris. Tom kind of said, here’s the idea, hand it to the engineers. So we worked and worked and worked and worked and worked on this pavilion. And we had, because of EPCOT, excuse me, I’m sorry, Disneyland, Paris’ financial challenges, we were given a budget and they said, you can’t go over this budget. So every month we’d go back through our reviews and we’d be a couple million over. So it goes back and forth over years and over months. We finally came to one final meeting and the man who was in charge, a really truly great man, I started my speech about, well, this month we were at 93, but we think we can get it down to 92. And he just said, stop, just stop, stop.

Whatever you’re saying, I don’t want to hear what you’re saying. There are these 50 people or 40 people inquisitions every month you go through this thing and you have to sit with the Project Manager and you have to justify your budgets. And it’s very intense. This man by the name of Mickey Steinberg, who was just a great leader as far as I was concerned, he just said, here’s what’s going to happen.

I’m going to the studio to sign an authorization for 90 million. I don’t want you coming back. You’re not asking for money. All you have to do is two things. You have to make sure this adheres to the program, which meant to be, it had to be at least 2,400 per hour capacity because of the demand. That’s what you always have on big E-ticket attractions for Disney. And the other thing is stay on budget now.

Get out of this office, get out of here. Just go make it happen. So we did it. We did it. We exceeded the expectations. The thing came in and about $600,000 under budget and it was a phenomenal success. And I spent from June of 94 to June of 95, spent 180, no, 179 nights in the Disneyland Hotel. I was traveling back and forth every week from Los Angeles to Paris. The project was a phenomenal success. The attendance skyrocketed up. They did a massive promotion, they did something else. And I don’t know if you’ve ever seen Shoot the Moon?

Dan Heaton: I haven’t seen it, but I would like to.

Tim Delaney: You should see it. You can find it on YouTube. Shoot the Moon was a television show that they were putting together, which was about three things. It was number one, Walt Disney’s involvement in space travel, which was the old “Man in Space”, if you can imagine that process. It was second underlying theme of the whole thing was promoting Disneyland Paris.

And number three was promoting the process by which Imagineering does projects, and they had somebody hosting that part of it and following this person all the way through the process. That person was me. And so I was like, so I look at that now and I’m trying to, there are times where I was just talking to people and I was like, I didn’t even know what I was talking about. The thing was completely incoherent. But I will tell you something, that it was a phenomenon in Europe, and I can tell you the number of letters I got from people just learning about this is amazing.

I didn’t know people, I want to do this. I’m in engineering. I didn’t realize that engineers had a place in theme park design and it was kind of amazing. So there is one thing that I really do want to stress is that when Disneyland Paris or Euro Disneyland opened in 1992, Europeans didn’t know very much about Disney. They weren’t used to it. The cast members we hired really didn’t know much about Disney. And it was just like, what’s the big deal? We were being crucified in the press.

This was going to be the cultural Chernobyl, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. But by 1995, 3 years of the park had been open and now you had people who have been to the park, they understood what Disney quality was all about. But this wasn’t some sleazy little carny thing. This was like a real turnaround. The cast members were so excited, they believed in what the Disney product was all about. It was phenomenal. So the opening for Space Mountain was the biggest event ever. I mean, they promoted that. I mean Coca-Cola put out with the Space Mountain logo on, they sold a hundred million of those. And the TV special, the opening for Space Mountain was phenomenal. The attendance jumped by 2 million.

Actually, I was going to tell you just prior to us opening Space Mountain, I had built, we had designed and built a full-size Nautilus indoor and outdoor, an exterior bottle of submarine and an inside show. That was done just like, I dunno, a year or six months before because we were continually doing the development. So you were going to remind me about Kirk Douglas?

Dan Heaton: Yes. I was waiting for the opportunity. Now is the time.

Tim Delaney: So one night at Space Mountain, I hid Space Mountain behind a berm or the site. So when we were building it, suddenly people were like, where do you get the land to do all that stuff? So anyway, we built the Nautilus submarine and we built this tour going through it and all that. One night I get this call like, hey, listen, can you meet Jeffrey Katzenberg?

He’s going to be walking the site with somebody. Sure. Can you map in the middle of Discoveryland or so? Excuse me. Jeffrey walks up or comes up to me and he has Michael Douglas with him. So we started heading towards Space Mountain, and as soon as Michael Douglas saw the Nautilus, he stops and he’s like, holy cow. He says, I got to tell you, when my father was doing 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea when he was doing it, he was in the studio all the time.

It was amazing. It was just fantastic. He couldn’t take his eyes off the Nautilus and it wasn’t open at that time. It was a lot of construction fences and all that stuff. So I said, well, my colleague, it’s really interesting you should say that because when I was working on the Living Seas pavilion, Kirk Douglas was actually hired by I think American Express to do some commercials and they were shooting down at the China pavilion. So they brought Kirk Douglas and we were working on the Living Seas pavilion. It wasn’t open yet, but they like to do a lot of backstage tour. So Kirk Douglas comes in into the queue line. I’m saying, and the queue line, I had gotten all these artifacts and I had gotten one of the eight-foot-long Nautilus submarines that Tom Sherman had built, and we had it on display there.

So Kirk Douglas was walking through the queue line and he sees the poster of the 20,000 Leagues movie, and he stops. He’s like, Kirk’s like, that’s really great. I’d love to get one of those. I go, anyone? I’m go, I’ll send you one. I had to get back to Los Angeles to do it, but I sent him this poster and Kirk wrote me this really nice letter, so go forward now.

I’m talking to Michael Douglas and he’s telling me the story about his father and all that. And I go, Mike, I got to tell you something. I met your father. I sent him a poster. He really wanted a 20,000 Leagues poster. I sent him one and he sent me this really, really nice letter. He looks and he goes, that’s my dad. He sends letters to people and he is really generous and he is really thoughtful about that.

So it was like this neat connection. So I said, well, you know what? I got to tell you the truth, Michael, when we open the Nautilus submarine here in Paris, I’m going to invite your father over to see if he wants to see if he can come over. He goes, wow, I dunno if he can do it, but you should do it. So I sent him a letter. I go, Kirk, I don’t know if you remember me, but I sent you that poster. He sent me another long letter. Of course Tim, I remember you and you sent me that thing.

Unfortunately I’m just not able to travel right now, but I’m sure you’re Nautilus submarine would be really something special. It was really great. So those are the kind of stories that, I mean, I don’t know that I’ve ever, I don’t know if I’ve told that to anybody, but it is these little things where you really find how, I saw that in Imagineering too when Michael Eisner used to promote and get a lot of celebrities that come through Imagineering and people have a different attitude.

It’s not like a studio. They’re very respective of the whole process of what the Disney parks are about, what they mean to people. Knowing you can get into Imagineering or behind the scenes. It’s very special; it’s not like a movie studio. It’s something that’s very special. And most of the people that I ever encountered, it could be Michael. I mean it could be Michael Jackson or Chevy Chase or John Landis. I mean, I took a lot of people on tours and it’s really special how respectful they are and how special it is for them. These are really top of the world celebrities, and it was really neat. So yeah, I’m glad I remember that because it kind of linked the Seas pavilion and Disneyland Paris together with Michael and Kirk Douglas.

Dan Heaton: That’s a great story. I think that’s a perfect example though of just how much impact the attractions and the parks and connecting to movies and everything and how much that transcends just passive entertainment. I love that you were able to tell that story. So I just have one more question, not specific to an attraction, more in general.

So you worked at Disney for a very long time, went through multiple eras of Imagineering and everything and had a lot of success there. I know there’s tons of people that are interested in either becoming Imagineers or moving some way into theme parks. I know there’s plenty of operators out there. What do you think it is, not what’s the secret, but what are some traits that maybe you had or that you saw that help to make you successful and are things that might be helpful for people to have working in that kind of environment?

Tim Delaney: Well, I’ll say that if you from the Walt Disney Company and you realize what is the strength of the company, where do they always excel? I know it’s a cliche, but it’s an absolutely positive one. The fact that everything is story-driven, everything has a meaning, and this is the basis of how I run my company today. I get a lot of calls from people who are looking for that Disney magic, and I do a lot of work and I do a lot of high profile work like I recently just did where for the Clippers, even something like I redid the football stadium at University of Notre Dame and I do a lot of work in Asia and people are all looking for whatever that Disney secret sauce happens to be.

Now, the difference happens to be that most people have the desire in most companies, I mean, big companies want to build something, they have the desire and they have, sometimes they have the money, but you have to have the will to be able to do it.

But for people wanting to start out, I think it’s really good. This is the best advice I can give to anybody. Learn how to be really good at something I know it doesn’t matter to me what it’s, I mean, you can be in any business, you could be if you be in Imagineering, you if want to be, you’re an artist or a model builder or an estimator or an engineer. I do a lot of stuff where I talk to engineers and I say that everybody, I considered everybody at Imagineering a creative person.

This includes accounting and finance and engineering. Because what creativity means to me is someone who’s willing to look at a problem and solve it in a unique way. Sometimes you need an estimator who’s going to say, you can’t afford to do this, but you could do this. So tell me how to do it.

So you really need to respect the teams that are around you, but understanding how stories are told. The number one rules of Imagineering, I don’t know if Marty Sklar wrote those, Mickey’s 10 Commandments. Number one is know your audience and there’s a whole list of them and know your audience. Walk in your guest shoes, learn how to maintain things, focus on the idea, tell a story that makes sense. Here’s the interesting thing, here’s a little clue you probably don’t know, and this is something that I’ve just kind of figured out forever.

We always talk about Disney being storytellers, but think about this. You have to tell a story without using words. When you walk down Main Street and you look at Main Street and you see a castle at the end, or you look at Skull Rock or you look at Galaxy’s Edge for Star Wars right now, you look at that and everything is there that’s telling you a story, but it’s no one sitting there telling you a story.

You bring your own story to it, but you have to communicate. You’re communicating stories in a visual way, and that’s from the artist’s point of view. But you also need, I will tell you right now, the way I run my business now is the way we worked at Disney. I have a guy who works for me, we work together. He’s a writer. His name’s Matthew Flynn, and he is an ex Disney guy. He worked in the gaming part, and he’s a brilliant writer, great concept guy, brilliant writer. I don’t care if I’m designing a food cart. We don’t do anything until we analyze the market. We write a story about what it is that we’re doing and why we’re doing it. Why would people come, why would they? You can write a story about, I don’t know, a hotdog stand, an 80-story skyscraper.

What you really want to do is you really want, you always work with people, you work with iconic people, you work with corporations. What you want everybody to do is everybody to be on the same page. This is why we’re doing this; this is who’s going to come to it. This is what the experience they’re going to have. Today, the world we live in, everything is about experience.

Everything’s about experience. We live in an Instagram world and everybody wants an experience. So you have to write the story and it’s crystal clear. The best thing for us before I start designing anything or drawing anything or doing anything like that is that we go in, we pitch, talk about the story. It’s like you need a road map. You can use any metaphor you want. It’s a road map. You can’t make a movie without a script.

You need to tell a story for theme parks or shopping centers or anything like that; you write it down. Then when you get everybody in the room, when they’re all heads are nodding up and down, going, yeah, that’s the kind of thing we’re looking for, then you can start the design. Then you can bring in the architects, then you can bring in the attractions people or the special effects people or the entertainment people or the retail people or the food people, because now everyone’s on the same page and they understand how things go together.

It’s a very, very, it’s most concepts that you deal with in your life. They’re easy concepts to understand, but very difficult to do. That’s what Disney does. One thing I do want to say, and I just got my wife and I just got back from San Francisco and I said, this time I’m into the Disney Family Museum up in the Presidio in about, I don’t know how many years, eight years or something, or I’ve been there a few times, but I haven’t been there in a while.

And I’ll tell you anybody who you want to get really charged up about creativity specific to Disney and Walt Disney himself. But I mean the way things get done and how incredibly talented people can be brought together by a man, it was so amazing. Like Walt Disney, go to that museum and look at it and it will recharge your batteries. I mean, it teaches you, if you look at everything, first of all, the exhibits are beautifully designed. Secondly, the story is being told about Walt and his struggles and the troubles he had and how he had to mortgage things and all that.

He continually was just driven by doing great things. And for me, it’s a special treat because I can hear the voices of Herb Ryman and more, and you hear all this archival footage and you hear all these tapes of these guys talking about philosophies from Disney. So it’s really great. So that’s the essence of what the Disney company’s about and what you can learn and what you should learn is be really great at something and learn how to tell a story and look at things holistically before you start. Everybody wants to get their pen out. Start drawing buildings that you have to know where you’re going before you can really get to a final solution.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that’s a great answer. That was so much more than I even expected when I asked the question. I really, really appreciate that. I think I have not been to that museum in San Francisco and it’s on my top of my list of a place to go, and I loved hearing about that. So Tim, thanks so much for doing this. This was amazing and I really appreciate it. It was a lot of fun and you had such great stories.

Tim Delaney: Thank you very much. I really appreciate it. And it’s fun for me to kind of trip down memory lane because I had really good memories and I had really great memories of really terrific people to work with and in common, we all created major things and it was very rewarding. My 34 years were very rewarding, so it was great. So I love talking about it, so thank you for the opportunity.

Leave a Reply