Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

As a theme park fan, I’ve often made assumptions about what it’s like to work as a Disney Imagineer. The role sounds amazing because it involves creating the attractions and places that I love so much. But what is it like to actually be an Imagineer? On this roundtable episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast, Don Carson and Chris Merritt help to answer that question.

Don and Chris both have extensive experience working as theme park designers for Disney and other companies. On this episode, they describe what inspired them to pursue this career and their fandom for theme parks. Don explains how his fear of The Haunted Mansion as a child pushed him to understand how it works. Chris describes his visits with legends like Marc and Alice Davis and Rolly Crump that encouraged his interest. They both have also learned the challenges to working in this industry.

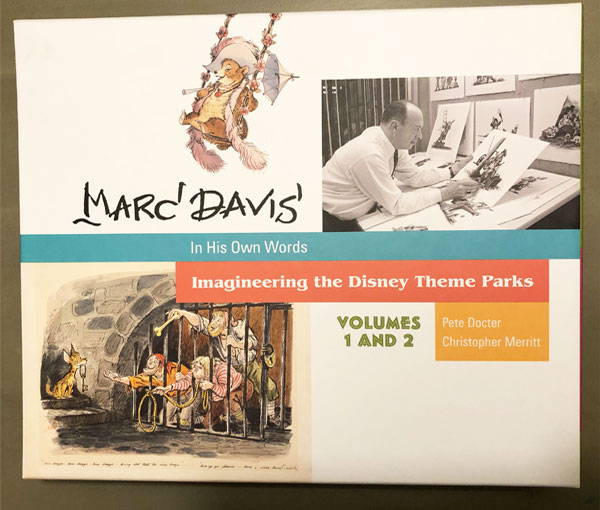

I really enjoyed how candid Don and Chris are about difficulties along with the successes. They both love theme parks, but that doesn’t mean it’s always an easy role. It’s a great conversation that covers a lot from their careers. Chris also talks about the amazing book Marc Davis in His Own Words that he co-authored with Pete Docter. He describes what inspired him to write such an extensive look at Marc’s career. Don also gives more background on his remarkable VR recreation of the 1958 version of the Alice in Wonderland attraction. This is easily one of my favorite podcast episodes.

Show Notes: Roundtable

Learn more about the book Marc Davis: In His Words by Chris Merritt and Pete Docter and purchase a copy on Amazon.

Check out Don Carson’s Alice 1958 VR Ride-through, subscribe to his YouTube channel, and follow Don on Instagram.

Listen to past Imagineering Roundtable episodes of The Tomorrow Society Podcast with Don Carson & Joe Lanzisero and Andy Sinclair-Harris & Don Carson.

Support the podcast through a one-time donation and buy me a Dole Whip!

Transcript

Don Carson: When my wife informed me that we needed to leave Los Angeles in the mid-‘90s and we moved out to Eugene, Oregon, I took whatever work I could get and it happened to be in the video game world. What I didn’t tell my bosses in the video game world was actually what I was doing was building theme park rides.

I was using their mechanics, so whether it was a mini golf game or it was whatever the game I was working on, I was basically creating themed environments and it was just when 3D was starting to integrate into computer games. So literally every single thing I’ve worked on has been just another extension of building a place and now I use those video game tools to build places, but it really, honestly, I think Chris, we share this is that we can’t not, this is what we do.

Dan Heaton: That is former Disney Imagineer Don Carson, who is back for another Imagineering roundtable along with our special guest, Chris Merritt, who is also a Disney Imagineer and the co-author of the incredible book, Marc Davis in His own Words with Pete Doctor. It’s going to be great. You’re listening to The Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks so much for joining me here on Episode 130 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. As always, I am your host, Dan Heaton. Some of my favorite episodes from last year were the Roundtable episodes. I did two of them and it was really the idea of Don Carson, who is a former Disney Imagineer, worked on Splash Mountain, designs for Toon Town, and so much more.

He’s been in the industry for decades, and I talked to him first in January of last year, had a great conversation and then joined Don and Joe Lanzisero and then Andy Sinclair Harris. He had a really great idea, which was why don’t we get two former imagineers onto one show and instead of making it more of a look back at their careers, let’s just talk about various issues and questions. That continues today with Chris Merritt. Chris spent a lot of time working for Disney involved in so many interesting projects.

He’s also an author who wrote books on Knotts Berry Farm and lately, like I mentioned in the intro, Marc Davis in his Own Words, which is a book that I picked up just last month, I cannot believe it took me this long to get it incredibly massive detailed book that Chris co-authored with Pete Doctor. And really, if you, I know it costs a lot, but it is worth every penny. I could not recommend a book more.

We talk about that a bit, but really what this roundtable is about is Don and Chris talking about what inspired them to become theme park designers, what continues to interest them in the medium, and then beyond that though, what are some of the challenges that they faced? And I don’t just mean challenges like your typical obstacle. A lot of it can be mental or just the toll that it takes to be working basically 24/7 on a project and then know that things are going to change.

It may not fit the original vision. And what’s that like for two people that have been in the industry for long enough to have worked on a lot of different projects, including ones overseas. To me, this was one of the more interesting conversations I’ve had in the entire history of the Tomorrow Society Podcast and also a lot of fun too. We really hit on quite a variety of points and issues that may face an Imagineer or anyone designing in the theme park industry. So I hope you enjoy this show and I don’t want to use up any more time. Let’s get right to it. Here are Chris Merritt and Don Carson.

(music)

Dan Heaton: I am really excited for this new Imagineering roundtable with two incredible guests. My first guest is back for his fourth appearance on the Tomorrow Society podcast. He joined Walt Disney Imagineering in 1989 and was the lead show designer for Splash Mountain of Walt Disney World. His other projects included Mickey’s Toon Town, Typhoon Lagoon, parts of Disney California Adventure, and so much more beyond Disney. He also worked in the gaming industry on virtual environments on many projects as a freelance designer. It is Don Carson. Don, thank you again for coming back here on this round table.

Don Carson: Thanks for having me. It’s always enjoyable.

Dan Heaton: Oh, definitely. It’s been a blast every time you’ve been on the show. My second guest, this is his first time on the show. He has been an art director and show designer on attractions for Walt Disney Imagineering and other companies for 25 years. His work for Imagineering included the Sleeping Beauty Castle walkthrough. He worked on Radiator Springs Racers, multiple attractions for Tokyo and Shanghai Disneyland. He’s also the author of Knotts Preserved and Pacific Ocean Park, and most recently co-authored the incredible book Marc Davis in his Own Words with Pete Doctor. Tt is Chris Merritt. Chris, thanks so much for me on the podcast.

Chris Merritt: Wow, I can’t live up to that, but thank you so much for having me.

Dan Heaton: I think that was actually a very short description of all the things you’ve done. I think I could have said much more, but I appreciate having you on. I think this is going to be great with both of you here on the show.

Chris Merritt: Awesome. Looking forward to it.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, so we’re going to talk today about a lot of bigger questions about theme park design and what inspires both of you to do what you do, which I’m excited to do here. Before I do that, I did want to ask one question to each of you about some projects you’ve done. Chris, of course, I have to ask you a little bit about your book on Marc Davis. So I know you’ve done some great podcasts, great interviews where you’ve talked about details of why you’re interested. I’m just curious for you personally, what really inspired you to get involved in such an ambitious project? What was it about Marc Davis and what he did that interested you so much?

Chris Merritt: Well, without going into the long and possibly excruciatingly boring history of how I got to know Marc and Alice and was really influenced by them as a Jungle Cruise Skipper and a young designer and all that, but I’ll say one thing because I’ve said that on other shows before. But I will say that when I was able to get to Imagineering, one of the first things I did was go into the IRC, which is the research library that Imagineering has and would take a look at the amazing collection of all the work that Marc had done.

I was flabbergasted to see the volume of it, but particularly things that had never been published before, things that the general public had not seen before because the guy was a machine. I mean, he just cranked out the most gorgeous designs and drawings, one after the other.

He was so prodigious. I mean, there are very few other artists at Imagineering who even come close to his output over his tenure there. And I always thought, oh my God, this is so amazing. This has got to be in a coffee table book someday. So I didn’t realize at the time that I and Pete would be the ones doing that coffee table book, but just the wealth of that.

I always felt rather strongly that there needed to be a really big deep dive look at his work because his design principles are really the bedrock of what we think of when we think of classic Disney theme park attractions. I think most people tend to think of Pirates of the Caribbean, the Haunted Mansion, Jungle Cruise, Country Bear Jamboree, America Sings, “it’s a small world”, and Tiki Room. Those are kind of things that kind of go to the forefront I think, of people’s minds.

He had such a strong hand in the design of all of those, so just to get that out. But then a plethora of other, I mean there’s a ton of work he did for the Florida parks and for Epcot with the World of Motion, and he really did set the ball rolling on what became The American Adventure at Epcot and just to find a lot even we didn’t even dig up until we got into this project, so many ideas for attractions that never made it, that no one had ever heard of.

He did this insane, this insane show pitch for a show. It didn’t make it for Monsanto, which was a carousel show, not dissimilar in operation to how Carousel of Progress works, but he did it with Ray Bradbury and the script is just bananas or things like he was pitching a Silly Symphonies themed dark ride at one point. So I just thought it was really important to get all this work out there and to celebrate him. My only regret is that he didn’t live to see it. I think he would’ve really enjoyed that.

Dan Heaton: Just looking in the book, I’m amazed because I knew that he had worked on all those things. But when you see just it back to back to back and the details like for Country Bear Jamboree going through every character and seeing his drawings and how close everything was, just as one example and for that for so many attractions, it’s kind of mind blowing how much of an influence he had just not just on those attractions, but what we think of as a Disney theme park attraction. It’s incredible.

Chris Merritt: Yeah, I thought it was really important that we were able to also kind of prove that by showing and not necessarily telling, although there is a great amount of text and a great amount of in Marc as the book title says it is in his own words, much of it, but I really wanted to prove that you’ll see a lot of juxtaposition in the book of his designs and then the install photos, and I always tried to hue towards choosing photos that were as close to the install date as possible because he would’ve art directed that in the field. I thought it was really important to show here’s what his design was and here’s how it ended up and look, they almost overlap.

Dan Heaton: It’s amazing to see. I can’t recommend the book highly enough and it’s a real achievement and I’ve read a lot of theme park books, so I don’t say that lightly.

Chris Merritt: Well, thank you.

Dan Heaton: Alright, well Don, speaking of things that are really cool, the last time you were on, we did talk about in pretty much detail your recreation of the original version of Disneyland’s Alice in Wonderland, which again, what I found so interesting recently is I watched your behind-the-scenes video that you put out a few weeks ago on YouTube where you kind of explained how it all came together, and the thing that struck me was how many different sources you were using. You have old photos, you have looking at the style of artists, the vintage plan, and you’re also working with other artists, then you’re trying to deal with the audio. So how challenging Don was it for you and the group to kind of bring all of those different things together into something that was like a coherent whole?

Don Carson: The research part was probably the best, most enjoyable part of it because we felt a little bit like we were on an archeological dig site because we had some reference. We had Daniel “Rover” Singer who was an Imagineer at the same time I was, who has a deep love of Alice in Wonderland and that attraction, and he was actually, the genesis of us doing that project was his desire to see it.

And we started out with little information and then just out of the woodwork we just got little bits coming in from fans who had a little extra piece that was especially true of audio pieces. It was a joy. And the thing was that we had our heads down so much on getting it done that from the day that Rover said, Hey, let’s do this to the day we uploaded it to YouTube was only two months. I don’t even know how that happened.

Chris Merritt: Wow.

Dan Heaton: Wow. Yeah, that’s the most mind boggling thing because when I watched the behind the scenes, I thought this is something someone could spend years on. But I guess that’s the world we live in right now.

Don Carson: I guess the reason we ended up doing it was basically what preceded it was I had done the Pumpkin Town, which was purely just an excuse for me to talk about the design steps that one could go through as they were designing a theme park dark ride, a really simple traditional dark ride. And when Rover said, Hey, let’s try doing Alice, it was like, well, here’s another opportunity to show off the tools that just didn’t exist until very recently that we as designers can leverage to communicate our ideas in a way that allows people to actually ride our ideas even in the earliest days of concept as opposed to purely just I have a drawing of what this might look like five years from now.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, totally. And I think that morphs really well into our roundtable type questions because some of the things we’re going to talk about relate to theme park design and how things come together for both of you. So I’m going to start with the first question here for you, Chris, which is, it’s a very big question. What are some of the key factors that are involved with taking a great idea and actually delivering an effective final product?

Chris Merritt: Well, key factors are certainly multifaceted, mainly just to cut to the chase, budget and time are the big ones. I was approached recently for a project that was going to go from blue sky to install in 14 months, which is just nuts. So you have to, I mean, time and money, which is many things in life. But other than that, from aesthetic, from an art director point of view, I think for me that’s a very personal thing.

But for me, I always try to hue very closely, if not exactly to, if we’re dealing with an IP situation, we’re trying to hue very closely to what you see on screen, what’s the emotional content in the IP that you’re using? So if it’s a film or a television program, something like that where there are characters and things that people are very attached to and very close to, you really want to hit those key moments I think for something.

Well, I think for something like the Sleeping Beauty Castle walkthrough, I think even though we were replicating what Ken Anderson had done in 1957, I still think people expect to see those scenes with Aurora and they really expect to see those scenes with Maleficent, which had been kind of excised from the 1970s version. So for me, aside from budget and time issues, which are big issues to be sure, I try to hue very closely to what the look and the feel of the film is, if not copy things outright because I think there are things that are people looking for in these experiences. You’re a fan of the Cars movies by Pixar and you’re going to ride Radiator Springs Racers.

There are surprises in that attraction that are not in the film, but there are key moments that are lifted right textbook out of the film. And I do think you have to strike a balance between those things. I think Don, I’m sure is familiar with this. There’s a phrase in the industry like, oh, you just did a book report where you’ve just, some of the Fantasyland dark rides are book reports where they’re just scenes taken straight out of the film and you’re seeing scene after scene. But there are some things that I think people do want to see in that vein.

Don Carson: One of the reasons I was so excited that Chris and I were going to get to talk together is that I realized that probably he and I have worked on more Dreamworks IP projects together. I tell you how many IP we’ve done with Dreamworks characters, but one of the things that we definitely stick to the film as far as pulling a lot of the moments, but we also mine the concept art a lot and in some cases, sometimes the concept art has stylistic choices that allow us to sort of leverage choices that went into the finished film to allow us to expand it.

We recently opened up the Dreamworks Waterpark in American Dream Mall in Rutherford, New Jersey, and it had a very small budget for the size that it had, and we had to stylize the Dreamworks IP tremendously. And where we went to find that inspiration was the concept art even more so than the film itself. So even though we weren’t, certainly weren’t trying to make a book report, we were trying to capture the essence of those IP and those movies, but we did it through the concept art as much as we did from the film itself.

Dan Heaton: That’s an interesting point because I think about even just for that example or some like your big Galaxy’s Edge or something or Pandora where it’s like those are very different examples, but Galaxy’s Edge where it’s like, well, we want to put in what’s happening right now, but is that what the guests want? The guests might want something else. How do we balance that out where it’s new, but it’s also familiar? How tricky is it to when you’re designing and you’re trying to come up with something that’s stylistically interesting and conceptual, then also to always have those business side of it in the back of your head, how do you balance that in a way that ultimately makes for a good attraction?

Chris Merritt: Yeah, it’s not always easy because I mean, I always try to be a responsible designer keeping it on budget. I certainly think this is going to sound kind of rough, but I think that’s the best way to tell an inexperienced creative director or art director who someone just comes in and comes up with this pie in the sky stuff that is just not achievable for the money that you’ve been allotted to do these things with.

But having said that, you really do want to push it as far as you can because I mean, I feel like at the end of the day, and the reason that I love theme parks so much is that attention to detail, that attention to quality and that extra step you put yourself in the place of the guest and how much money they’re spending to come to these parks, just especially people who are on a family vacation, I can’t even fathom what some people spend.

So you really want to do your best to deliver as much as possible in that situation. Sometimes that means getting creative with things, and sometimes that’s knowing when not to fall on your sword for something that seems like a big, if you can trade one big thing for 20 smaller or medium things, that’s when you spread it all out, is going to give more satisfaction to people, if that makes sense. I would go for the spreading it out with the 20 things just because there’s so much more to take home from a mental emotional standpoint.

Don Carson: I think to also hearken back to your question about what it takes and bring it to the finished product, it’s easy for Chris and I because we’re at the very beginning of the process to think that we are the process, but really it’s about three or four or 500 other people are going to touch it. Our job is to distill whatever that story is or what the premise is of the attraction into something that is easily grasped by the rest of the team.

And hopefully if we do our job right, they’ll argue for us the choices that are made. Sometimes those choices have to be fairly simplistic, broad ones that everybody can understand, and then you actually find that people are actually doing the fighting for you. But that’s tricky, making sure that you get that right. You want the entire team to own it as much as you feel you do, so that the finished product with any luck looks like what you intended it to in the beginning.

Chris Merritt: I think to get back to Marc Davis, not that we’re talking about Marc, but he would selling the idea in a single sketch, and if you can generate a piece of artwork like Don says, that gets the entire team excited and behind you and ready to fight for you because you’re going to need those people to fight for you with the people who own the purse strings. That’s huge. That’s not always easy to do, right?

Don Carson: Yeah.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, totally. I mean, that’s the trick. I mean, you see, like I said with that book where you mentioned the 20 small factors where I was looking at the Haunted Mansion and there were things I was like, I don’t remember ever seeing that. What I mean by that is there’s so many little things and good touches that I’ve been on the attraction a million times and haven’t even seen it. But that gets me to the flip side a bit of what I asked, which is time and budget are two huge factors and obviously having a great concept, but what is an undervalued or lesser known aspect that’s really crucial to design process? Let’s start with you Don.

Don Carson: Well, I’d say that probably as I said before, this ability to create rules by which the universe of the attraction functions. Certainly for Splash Mountain, it was there’s a world of critters in the worlds of humans, and then our design choices were based upon whether or not the thing was built by a human or a critter. That seems so incredibly simplistic, but it became the backbone of how we all understood how the two aspects of that attraction coexisted.

And similarly, when we were working on the water park for American Dream, it did not have enough money for us to recreate Madagascar or the world of Kung Fu Panda. So we went with a very graphic approach, and rather than suggesting that we were delivering on Madagascar for a water park customer, we had the characters come to the water park and infuse it with their personalities, which was a much more graphic overlay as opposed to our attempt to create a jungle.

Chris Merritt: One thing that has saved me multiple times, this is something I picked up from Rolly Crump. Rolly had left Imagineering in the late 1960s, early ‘70s, and had done a lot of freelance work, and he designed probably the most charming little dark ride he had ever done for Knotts Berry Farm called Knotts Berry Tales. That had a huge impact on me as a little kid.

But from a design standpoint, one of the things that I got from that attraction was that ride was certainly not sophisticated at all. The animatronics were very simple on off, very simple movements. They were not animatronics, I wouldn’t even call them animatronics. They were like mechanical gags with a little bear waving up and down. But what Rolly did that was so brilliant was he flooded the zone with graphics, signage and wanted posters and amazing, you can imagine Rolly Crump’s color sense.

And this ride was Crump unbound. So if you do some Googling, look up Knotts Berry Tales to see some photos of what I’m talking about, but the graphics. So for me, I’ve always thought if you don’t have the budget to go to recreate the world in excruciating detail like they’ve done with the Star Wars properties and the Galaxy’s Edge, but you’ve still got to give the guest a sense of it. Graphics is a really great way to bolster what you have going on. I did a lot of that at Universal Studios Singapore in the Shrek Land, and you’ll just see even, and hearkening back to what Don said before about using the concept art.

I’m not necessarily a big fan of the Shrek aesthetic or the films in general, but what I did find is when I dug into all the concept art, how much work all the artists had done in creating that world, and I found all kinds of graphics and ideas for things that I lifted whole cloth and put, well, they don’t call it Shrek land, they call it Far, Far Away at Universal Studios Singapore.

So you’ll see areas where we had long hallways exiting the attractions, and we had no budget for high-end theming or even fiberglass stonework replication we’re painting the stones on the wall. But I bumped a lot of that up with a lot of graphics and some of it, again, these are things that I lifted whole cloth out of the concept art. So signage and graphics I think is a good tool to keep in your tool belt.

Don Carson: Without a doubt. And if I can add too, before working at Disney, I worked for the Renaissance Pleasure Fair, and I think my fair budget was like $3,000. And so then to go work on an attraction or the budget was a hundred million dollars. I figured that any attraction could fall between those two budgets.

Dan Heaton: I should mention Knotts Berry Tales. I live in Missouri, so we haven’t been out there to California that much when I was younger, but we went to Knotts Berry Farm when I was nine, which was in 1985, and I rode that, and I remember almost nothing of that trip. I remember the Soapbox Racers and I remember Knotts Berry Tales, and now I look back at it and you watch the videos, which are kind of not great online quality because older and it’s hard.

There’s so much going on. I mean this in a good way, it’s hard for your brain to almost wrap your head around everything you see because without a clear vision like you’re writing it and you’re looking at all, like you said, all the graphics, but it shows just how effective that was because again, I don’t remember. I remember it being really cool even as a nine year old, and why would I remember that however long? It’s been a long time since I rode it.

Chris Merritt: Well, the good news is it looks like Don’s Covid lockdown “keep yourself occupied” project was the Alice ‘58 recreation. My lockdown project has been, I’m doing a new book on the history of Knotts Berry Tales, and we’re working with Rolly Crump on it, and he’s writing the intro, but we’ve spent all summer and fall of last year tracking down every single person who was still around who worked with Rolly on it. We found concept art and photos, construction photos, and really beautiful photos of the actual attraction. They’re all going to go on this book and hopefully it’s going to coincide.

They’re actually redoing the ride. It’s going to be in a different format, but that’s going to hopefully be open by this next summer. So that book will hopefully be out by then. I’m still working on the first draft, but we’ve got so much stuff to show. So I think you show people a video of Knotts Berry Tales, and they go all whatever, but riding through it was a very different experience, as you say, and I think some of these photos of it will really show what that was.

Don Carson: That’s great. That’s the one I want to go back in time and ride again.

Chris Merritt: Yeah, me too.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, because I’m excited about this new version, but it’s going to be, I think mostly computer effects and everything, which is cool they’re doing it. I think it’s going to get people look back at your book and other things, but it’s very different.

Chris Merritt: Well, I’ll tell you what, I’ll let the cat out of the bag a little bit more. I was lucky enough about four weeks ago, they gave myself and my co-author a sneak peek at the new ride, and I was actually a little worried, and I’m really glad to say it’s wonderful. They put so much more set in that attraction. It’s not just screens, it’s really super charming. And Chris Crump rode it. Rolly’s not in shape to ride it right now, but Chris rode it. We all agreed. I think it’s a hit, so it’s not going to be as it was. It’s not a little dark ride with all sets, but boy, they’ve got a lot of stuff in there. I can’t tell you how cute it is.

Don Carson: Oh, fantastic news.

Dan Heaton: Can’t wait. That makes me even more excited to see it. I want to get back out soon to parks. Well soon meeting a relative term, but when I’m able to and everything’s open, but that sounds super exciting. Alright, well let’s get to our next question here, which let’s move on a little bit to inspiration. I think that’s a big part of, I know for both of you and your stories, what interested you about being a designer. So let’s start with you, Chris, which is very simple question. I mean, what really inspires you to, you mentioned you love theme parks just to be a designer in theme parks.

Chris Merritt: Yeah, well, I’m sure Don would agree. It’s definitely a choice.

Don Carson: It could be an ailment actually.

Chris Merritt: It could be a chronic symptom of some sort that we desperately need treatment for. When I talk to younger designers, which sounds funny, I think all of us still think we’re 20 in our head, and I’m just turned 51 when younger designers come up to me, I do tell ’em that. I say, you need to realize it’s a choice. And it’s not necessarily an easy one.

I mean, I’ve had to pack my family up and go live in Singapore for four years or go live in China for three years and you go where the work is. I think the crux of what you’re asking is what gets me excited and enthusiastic about it; I got to say it really all stems from, I was really lucky enough as a kid in the ‘70s to get to go to Disneyland and Knotts Berry Farm a lot, and those attractions had a deep, deep impact on me.

And I didn’t really realize it until I went to CalArts to study animation. I didn’t really come to this realization until I actually got there that I wanted to do theme park design. But the things that Marc and Alice Davis worked on, Rolly Crump, Sam McKim’s concept art, John Hench’s ‘67 TomorrowLand is like unparalleled design and not Sperry farm with not Knottsberry tales. And then Bud Hurlbut who designed the log ride and the mine ride at Knotts Berry Farm, Eddie Sotto, who I got to work with at Imagineering later on, designed the Wacky Soapbox Racers, all these things that made this huge impact on my five- to 10-year-old brain that stuck with me forever.

Whenever I’m thinking of these things, I think about these things and I get excited just the memories of them and how interesting and different they were and how fascinating they were to me. So I try to put that in the things that I’m working on. I’ve worked on several Frozen attractions and I’ll be just fine if I never have to design anything with Frozen ever again. But I still try and put that excitement in there because there are kids who are going to ride that and they’re going to have the same experience that I did. I don’t know, Don, if you had the same, what’s the word I’m grasping for? If you had the same…

Don Carson: Epiphany?

Chris Merritt: Epiphany, yes.

Don Carson: Yes. epiphany. Well, absolutely. That was actually one of the reasons I was excited to get a chance for us to talk was that I could see our kindred spiritness in the work that you have been posting. My genesis moment was when I was, my grandparents lived in Anaheim. We grew up in San Francisco and we would go and as a seven-year-old, I was incredibly terrified of the Haunted Mansion, just hid under my mother’s jacket the entire time.

We had a couple of years where the income was kind of like it is right now. It was a little tight. So we didn’t make trips down to Disneyland and I was about nine and I realized I’m going to go to Disneyland and I’m still going to be under my mother’s coat through the Haunted Mansion. I decided I would learn how all the effects were done and most of that there was no Internet, so most of it was deduction.

So here I am showing up as a terrified nine-year-old to ride the Haunted Mansion. I realized that I was completely, utterly fascinated by the effects and I had not realized before the attention to detail that was happening in the grates over the doors or the handles on the rope stanchions or the wallpaper. And then I stumbled out of the Haunted Mansion and realized that those things were happening throughout the entire park. And finally the last sort of pushed me over the edge and made me realize that this is what I wanted to do for a living. My sister and I were walking through Frontierland and they were cleaning up or refurbishing what was the Mexican restaurant next to Big Thunder.

So they’d taken all that adobe, that mud, adobe walls, and they’d painted it basically beige, so it didn’t look old anymore. It looked like they just painted it with latex. There was this painter guy on a ladder with a coffee can and a cigarette because what you did when you were working as a painter, a Disney man, and he had this goop and he was dripping it down the walls of this newly painted adobe and scrubbing it in and making it look like it was old. And from that second I went, that’s what I’m going to do for a living.

That’s a job. That’s what I want to do for a living. There was no easy path in 1977 to go call up someone at WED and say, I want to be hired by you. But that feeling. Then lastly, the realization that I’m in a boat with a pirate ship firing cannons over at a fort, and I’m actually physically only about a hundred yards away from my parents’ parked car, that blew me away. That one could create a place that was so incredibly immersive. So all those emotional experiences are sort of my Geiger counter when I work on anything is am I able to transport people into places that are as deep and as rich as the experiences I had as a kid.

Dan Heaton: Those are great. I mean, just great to hear those stories. And now kind of on a related note though.

Chris Merritt: Don said that it much better than I did.

Dan Heaton: Both of them were great. I’m not judging. I thought both were excellent. I’m impartial. But I will say too though, I have kind of a related question because you both come in big fans of theme parks, you were interested in doing this upfront, and obviously both of you have worked at Imagineering, you’ve worked on other projects, you’ve both mentioned as you’ve kind of gone along as a designer. How have your working in the industry, how has it changed even what you’re interested in or how you approach things? Because obviously you could get, I’m not talking about really being jaded, I’m more just what you’re interested in. How has that changed as you’ve gone? I’ll ask Don first.

Don Carson: Well, I think I’ve been thinking about that specifically in sort of the arc of a career. And I’m in my late fifties, so I’m a little further along in the decrepit scale, Chris. But when I think of myself as an eight-year-old, I think of myself with my tongue out, sitting on the kitchen table, drawing. Then you go to school and you learn how to be an artist and then you march into the world to conquer it with your art.

And then you feel as though that the work that you’re doing is all about the project you get to work on. Then I’d say in midlife, you all of a sudden realize that the actual project you’re working on is not as important as who you get to work with sometimes. Some of my absolute favorite attractions that I’ve worked on or any project I’ve worked on were my favorite because of who I got to collaborate with.

As I’m getting older, I’m realizing that I’m more in a mind space to give back to young people who were in the position I was in the early ‘80s to help them make the life choices. I can feel that the trajectory is that I’m eventually going to end up back at eight with my tongue out drawing on the kitchen table. And that each of those phases brought a certain kind of joy and fulfillment.

But I am personally finding that I am, I would say that I am as pleased with how Alice came out as I am any physical thing I’ve ever done. That was utterly because of the conversations and the collaboration I had with the people around me. I would argue that I actually created a rideable attraction that you could experience. Unfortunately, it’s not made of concrete, but that doesn’t mean it’s not potentially as enjoyable.

Chris Merritt: But it’s so wonderful that you did that. I think we need to do that more with more lost attractions because unlike the medium of film, the medium of theme parks is you can’t go back and revisit it once it’s torn out. A film is a film and you can revisit it like an old friend anytime you want, and those feelings of nostalgia come back. But I can’t ever ride Adventure through Inner Space again. I can’t ride Knotts Berry Tales as I rode it as a kid. Again, I can’t ride Nature’s Wonderland. I experienced it as a little kid again, and I miss that. So I think it’s really actually important what Don did with the Alice 58 VR. That’s as close as you’re going to get.

Don Carson: That wasn’t an option until we were done. So even though it doesn’t completely give it back to us as a physical experience, that we can smell and smell the grease and hear the bleeding of the scenes through the very way too thin walls, we do get to have at least some kind of inkling of what it must’ve been like

Chris Merritt: To talk about Florida stuff. It kills me. I never got to experience Horizons.

Don Carson: Oh no.

Chris Merritt: I will never experience Horizons the way it once was. And so if that’s as close as you’re going to get, so I think the kind of research, the things that Don and I are both fans of the history of these things, I think it’s really important to document these things as much as you can because how else are future generations going to know about it?

Don Carson: I agree with that. You’re here.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. I mean for me, you just mentioned Horizons, like the ones that I rode as a kid that really I missed the most are Horizons, World of Motion, and Imagination plus If You Had Wings and some of the other Tomorrowland things that I rode in Florida are Great Movie Ride and some of the more recent ones. So that’s really important though because I think about it, I know there’s some great YouTube videos that have been put together of those, but it’s not the same as even something to another level.

I wish there were ways, even what you did was amazing, but even officially, I feel we talked about this on the last roundtable, actually, Don officially, I feel like especially given with all of us at home, there’s a need from people. If the company was interested, I think in doing something like that, and I don’t totally understand why not. I’m sure there are reasons, but I think it’d be amazing for fans to see.

Don Carson: I do question it, Chris, you’d know better than me, but my guess is that they probably don’t have as much perspective on their own product as maybe people on the outside.

Chris Merritt: Without getting into it too much, I think maybe Don, you’ve experienced this, it’s not always a benefit to your career to be a passionate fan of the history of it. So I will say that one thing I wanted to say, you mentioned If You Had Wings, which again is something I never got to experience, but don’t you think If You Had Wings is kind of Claude Coats sister attraction to Adventure Thru Inner Space. I mean, there’s a lot of similarity in the vehicles and how they move and the overlapping use of projection juxtaposed with the show set. Very interesting. That’s another one I wish I could go back in time and ride.

Don Carson: Although I still have the song in my head.

Dan Heaton: Oh yeah, I’m sorry about that.

Don Carson: The earworm of all.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I referenced that because I mentioned that same trip I rode Adventure Thru Inner Space, and I remember we were like, oh, this is kind of like If You Had Wings. It’s similar because again, especially the introduction where you kind of go by the microscope and go through that is very similar ride system, the whole deal. Well, Chris, I also have to ask you too though, I mean in your career, how has your perspective changed just what you’re interested in?

Chris Merritt: Boy, you mean just in totality of all art and culture or?

Dan Heaton: Well, you could take it however you would like. I know that’s probably too big for one answer, but just something that’s really changed for you in terms of an interest.

Chris Merritt: Well, because one of you or both you joked about being jaded, but I think you can’t help but get the longer you go on, you do get jaded about certain things do. I know for me, when I was in my twenties, I was definitely very starry-eyed and came at it with, oh my God. In fact, I’ll never forget. I was really fortunate in that I got my toe in the crack at Imagineering thanks to my good friend Larry Nikolai. The first thing I worked on was the model for the Sinbad attraction.

And Larry was really nice and knew I wanted to be a designer and let me design some of the elements of that show. But mostly I worked on the model and I just remember that first week I was there. And it’s so funny now because in retrospect, after doing the Marc Davis book, realizing how important that space I was in, I was working in the MAPO facility and the far end of the MAPO facility has a model shop.

And that model shop was basically the R&D area of WED when they moved over from the studio to Glendale in the 1960s. So like Bob Gurr, Roger Broggie, and guys like Wayne Jackson and some of these early machinists all worked in that space. Anyway, so we were working on the Sinbad model in that space. I of course didn’t know that at the time, but I just remember I was working on the paper version of the model and taking Larry’s drawings and making black-and-white xeroxes of them and shrinking them down to scale and spray mounting them onto foam core and cutting ’em out with exacto knives and making this first version of the model before we got into sculpting. I just remember thinking, wow, I could die happy right now. This is the coolest job in the world and I’m getting paid for it.

I mean, that’s amazing to me. So I’m not as I was in my twenties, but I think it is really important no matter if you get jaded or burned out, because these projects, especially when you relocate and go overseas, it’s really easy to burn out. It’s a lot of fast on your feet design, you’re racing against the clock, you’re racing against the money, and how do you keep your spirits up?

I think it’s really important to try and tap into that sense that that 10-year-old kid who rode the Jungle Cruise in Anaheim or who rode, Bud Hurlbutt’s Mine Train ride at Knotts, and what a sense of wonder you have. It’s really important to try and keep that as part of you because there are a lot of people in our industry who I’ve just seen it beaten out of them and you see it in their face, man. I mean you just see they’re done. They’re done. I don’t ever want to get that way.

Don Carson: Yeah, well that’s never asked the designer what his feelings are about the thing he just finished because they can only see the missed opportunities and the cuts.

Chris Merritt: Oh my God. It’s so funny you say that, Don, because if I could steal a story from Eddie Sotto. So when I first met Eddie, it was before I got the chance to, I worked with Eddie on the Winnie the Pooh Ride for Tokyo, but before that we were friends. Classic.

Don Carson: An absolute classic.

Chris Merritt: That’s my favorite one. But anyway, Eddie, I did a little student paper on the history of Knotts Berry Farms Roaring Twenties section, and I interviewed Eddie, so I was like 22 or something, 23. And I interviewed Eddie about his work on the Wacky Soapbox Racers, which I loved. I loved, I still love, I think it was genius work. Eddie is an amazing designer and just an amazing person in general. But anyway, I remember asking him, I said, so you worked really hard. You got the Wacky Soapbox Racers open and that first opening day, and you’re sitting there watching happy guests ride it and come out of the exit and what are you thinking?

And he told me, he said, it was awful. I hated it; I was so depressed. I sat there on a bench because so much of what he wanted was value engineered out of the show. They just couldn’t afford to do it. And so he sat there focusing on all the stuff that didn’t make it and all the stuff that, and his wife said, what’s wrong with you? Why aren’t you happy? Look at all these happy people. He said, so that’s your curse as a designer to know what your intent was and what it actually is. I don’t know where we’re going with that other than that’s a thing.

Don Carson: I swear for the 10 years after Toon Town opened, we would go to visit the park as a family. And my wife would say, do you want to go to Toon Town? I’d say no.

Chris Merritt: But see, I got to say I’m such a fan of Don’s work on Toon Town. Don’s artwork was some of the stuff that I would look at in the library when I was just starting there. I’d be like, oh my God, look at this amazing zippy cartoony style. And then when Toon Town opened, I was like, look, they didn’t use any straight lines in the architecture and how hard that must’ve been. And it was all related to him and Joe’s designs. So I look at it having not worked on it at all, and I’m like, oh my God, it’s amazing. Whereas Don probably never wants to see it again.

Don Carson: Well, I have stories, but the gift of the reading through cover to cover both covers of the Marc Davis book was realizing what humans they were. And it was even descriptions of where Marc would come up with gags and they were seen as gags by other Imagineers, and then some wouldn’t get in because it just wasn’t room for them. It wasn’t because they weren’t good gags. It was just wasn’t room for them. His sort of frustration that my favorite, the gag didn’t make it in. That’s the reality of this job is, I’m sorry, there’s an air conditioned duct going where you wanted that pivotal moment to be.

Chris Merritt: Yeah, let’s talk about that. Let’s talk about architects. You’re working on a project, right? You’ve got a drawing package and you’re reviewing it and you’re like, okay, okay. And then you get out into the field and you find a freaking HVAC duct has been put right in the middle of your show set and you’re like, dammit, you got to deal with it. That’s where I think a lot of the artistry comes in, by the way, is being in the field and dealing with that stuff and still making it look cool.

But Don, you were just saying about Marc not getting all his gags in even worse is the Enchanted Snow Palace at the end of his career there where he’s trying to pitch projects like let’s do something. And he does the Enchanted Snow Palace. And if you’ve looked at the book or the artwork, it’s the most gorgeous, beautiful jaw dropping watercolors you’ve ever seen. Great idea for an attraction. Marc told me he couldn’t even get any of the executives to come in and look at it, or the few that would go, oh, that’s nice, that’s nice. And then they’d walk right out again and he let it get to him. I mean, to be frank, it’s hard not to, right?

There’s a story, it’s in the book, and from another colleague of his where after that happened enough times, he just kind of sat there looking out his window, looking out at Flower Street, just kind of staring, which was not like him at all. So part of the problem is with these projects, and again, I’m sure Don, you can relate, is you do put so much of yourself in them. And so if you’re working, I don’t know, a nine to five job where you’re not emotionally invested in the outcome and you’ve put so much of yourself in it, I think it’s real easy to go, okay, whatever on this one.

But when you’re emotionally invested with it, that can be a really hard thing to deal with. Sorry to go on and on, but one other quick thing. Rolly Crump told me a similar thing when I was in my early twenties and I was trying to figure out how to break into the industry, and I was visiting Rolly along with Marc and Alice.

I visited Rolly, had an avocado ranch out just near San Diego at one point, Fallbrook, and he said, all right kid, you want to learn, you want to get into this industry. He sat me down under an avocado tree and told me all the really awful stories that can never be printed of his time at WED and how he was treated by some people. And I mean that was, and of course, so he said, you still want to do it? And I said, yeah, of course I still want to do it. I was 22. But you have to really love this medium and you give up a lot to do it, I guess is what I’m trying to say.

Don Carson: Yeah. My story is that I am pretty mild mannered. I’m hopefully relatively easy to work with. We were working on Toon Town and we were in the field, and when you build buildings that don’t have straight lines and they all do really wacky things, stuff happens and things that you had thought were precious, just have to go back in the truck because there’s just no room for them. So there was a hundred times a day where you were having to go, well, I guess it’s going to look like this.

Then you were just constantly trying to see if it still retains the look you were trying for. And at one point I get a call on my radio when we had radios back then that there were pouring the concrete slab around the Toon Town Trolley and that they were pouring it wrong. And I went, okay, so I get there, and sure enough, the truck was just about to pour concrete on this thing.

I said to the person who I will not mention in management, this is incorrect. And he said, well, we’re following the drawings you signed off. I said, well, show me. So we went to the construction thing and they showed me, they were looking at a drawing package where that curb was the size of my fingernail, and I dug into the pan and I said, no, no, no. I opened up, there was a diagram that showed just that curve with my signature on it. I said, that is what you’re supposed to pour to. And I said, but I signed this. This is what you’re supposed to do.

He said, no, no, we’re following the detail that’s relatively small. So I said, no, you really have to pour it this way. It’s how it was designed. So they poured it and then the guy took me by the arm and he led me away from the site. And he said, look, at one day you’re not going to get everything the way you want it.

And the only time in my entire career, entire career, I just exploded. I just could not believe I had spent months. Everything was a compromise to try to get it to all work. And afterward, my fellow designers, including Joe, said, are you all right? And I said, I have never felt better in my entire life. I had burned everything out. But that’s really, really to answer the very first questions you were asking. So much of our work is shepherding this herd of cats. This one agreed-upon design aesthetic and knowing along the way, there’s on a daily basis, going to be a hundred things that are asked of you to reevaluate whether or not your choice really is that important,

Chris Merritt: Man, you got to live there. You have to live there in the field when you’re in production and you’re building it because if you don’t, you will just get screwed. And if Don hadn’t been there for that, you know what I mean? So that didn’t mean anything to those other people, but it meant something to Don who did the design. This is really wonky, Don, have you seen both of you? You know what cloud revisions are right? On shop drawings? So a cloud revision is if you are getting architectural drawings back from whoever’s designing what the vendor in the field’s going to build, you make notes around things that people will make a little bubble around it. It’s in a little cloud shape.

So it’s called a cloud revision. There’s this great, I’ll have to dig it up for you. There’s this great picture going around there. So someone put a cloud revision on a shop drawing, and then they got out to the field and someone actually dug into the concrete, dug out a cloud shape that matched the cloud revision bubble. Exactly. But that happened because that person was not there to see ’em do it or catch them doing it.

You have to live there. That can get exhausting. I mean, I remember in the castle walkthrough, I had to be there in meetings all day nine to five, and then come back at two in the morning when the night shift was doing their work, because if I didn’t, by the time I got back at 9:00 AM the next morning, something would be installed wrong. Once it’s installed, you’re going to have a big fight with your project manager about uninstalling it and making it right.

Don Carson: It’s money jackhammering out that concrete thing. They poured wrong. It costs money.

Chris Merritt: Oh yeah. One of the scenes in the castle walkthrough, at some point in the ‘70s, they moved this massive transformer in there and they had to relocate that transformer for us to get all our show set in there. That was a big deal. Things like that, you have to be on top of it. This is really probably way too wonky for your audience.

Dan Heaton: This is great. I am enjoying this. I’m almost like I’m in the audience right now. This is wonderful. But I mean, really, I have to follow up to that. I really want to know though, because I mean the way you describe it, like you mentioned Chris, with burnout and such, when you’re designing something, you put so much heart into, whether it’s Toon Town or anything, how do you survive? What do you do mentally or physically? How do you cope with that in order to stay in the industry and not burn out? Because both of you have been in the industry for a long time.

Chris Merritt: I don’t know if this is a great answer for you, but I just feel like in my career, this is what I do. This is what I trained to do. This is what I decided I wanted to do in my twenties when I was at CalArts, I’ve told this story before, but I went to CalArts for character animation, and after my first year of animating, I really decided, oh, I really don’t want to be an animator.

I can’t sit there drawing pose after pose after pose all day long and just I don’t have the patience for it. I just really want to do theme park design. But back then in early ‘90s, much like Don, how do you learn how to do this? There was no way to learn how to do this. There weren’t even hardly any books or any information on the history of these things.

You had to find it out for yourself, which is one of the reasons I tracked down Marc and Alice Davis, and Rolly Crump, and people like that. So I could ask them, but for me, I’ve invested so much energy and passion into this and when I’m working, which a lot of us aren’t right now because of the COVID situation, but I am pretty good at what I do, and so it just feels like this is what you’re supposed to be doing.

This is really, certainly, there’s always times to pivot in your life and try new things and be, that’s what I’ll end up doing. But for me, I just have a deep, deep love for this and I’ve invested so much time and passion and a lot of my life into it. I can’t imagine not doing it or not caring about it. I don’t know if that solves the burnout question or not.

Don Carson: Well, I’d say that I think one of the reasons we do it is because we can’t not do it. That when my wife informed me that we needed to leave Los Angeles in the mid-‘90s and we moved out to Eugene, Oregon, I took whatever work I could get and it happened to be in the video game world. What I didn’t tell my bosses in the video game world was actually what I was doing was building theme park rides.

I was using their mechanics, so whether it was a mini golf game or it was whatever the game I was working on, I was basically creating themed environments and it was just when 3D was starting to integrate into computer games. So literally every single thing I’ve worked on has been just another extension of building a place and now I use those video game tools to build places, but it really, honestly, I think Chris, we share this is that we can’t not, this is what we do.

Dan Heaton: Totally. Yeah. Both answers make a lot of sense to me, and they totally hit on the burnout question, Chris, so that’s totally cool. So I want to finish with one question that’s kind of a bigger question related to how both of you view attractions when you’re a designer, and there’s attractions that have been amazing high tech things that haven’t done that well. Then there’s other ones that are fairly simple that have become classics that you just look at and you go, that’s a classic attraction. So I’ll start with you, Don, looking at it from a designer’s perspective, what do you think, what makes a difference in really making an attraction become a classic versus just something that’s okay?

Don Carson: I reflect on the movie industry and that there is not a single movie production no matter how low budget that went out of their way to make a bad movie, they were all going to make the movie that was going to change everything. I think that every attraction, everybody’s pouring themselves into making the best thing possible. And then for whatever reason, it is pushed away by the public or embraced and loved by the public. Sometimes that attraction can be loved despite itself. I remember when in the mid to late ‘90s, well the mid early ‘90s actually, when the Muppets were owned by Disney for the first time, they were talking about actually were replacing Mr. Lincoln for a Muppet animatronic show.

And it was like picketing. People were so angry. Now granted, these are the same people that wouldn’t be caught dead going in there unless they needed air conditioning, but the way they were passionate. So what defines a classic is often out of our hands. So that really it boils down to we just make the best thing we possibly can hope that we poured as much love and attention into it. Then also, there’s the other thing too that I think that sometimes attractions that have gone away that were much loved, if you had a chance to go back to them, you probably wouldn’t love as much. Probably kind of like the, at one point I made the mistake of watching HR Puff and Stuff on YouTube.

Chris Merritt: Oh my god. I was just going to say this. Sorry to interrupt you. Go ahead.

Don Carson: Oh, my childhood was a lie. It was definitely more ragtag than I memory of it. I have fond, fond memories of it. I think also that was part of the opportunity to do the Alice thing for Rover. He wanted to do it. He just thought the thing was as freaky and odd and strange compared to what we do now. But that freaky odd strangeness is what makes it so great. It causes you to reflect on the mechanics and the technology and the personalities and talents of the time, like an archeological dig.

So I don’t know. I don’t know any, I think having been alive long enough that someone, I said, oh yeah, I remember as a kid we were watching the Frost and Nixon interview, and a woman who was in her late thirties went, you were alive then. Sometimes, yes. It wasn’t that long ago that sometimes things are considered classics purely because they’re older. I can’t believe you were there, but you ate at the Big D back in the early ‘90s.

Chris Merritt: Oh God.

Don Carson: So it’s all relative. I also think the other thing too is that it depends on who grew up with it. That sometimes the things we love that we grew up with, we love because we grew up with them and they become classics. They’re just utterly connected with our childhood and we have our own mini Ratatouille moment when we ride something that we rode as a kid. So it becomes a classic in that respect.

Chris Merritt: I don’t think very many people were thinking about how Los Angeles was in the early 1970s and were really super nostalgic. I think the amount of people who were really nostalgic for that and what was being played on the radio then are probably relatively small. And then Quentin Tarantino does Once Upon a Time in Hollywood film, and he just brings that alive.

So to your point, Don, some dinky little thing that even if you could get in your time machine and go back and visit, and maybe it would not be so impressive, maybe it means more to someone who grew up with it and have that fleeting memory of it. I know I feel that way about Nature’s Wonderland. I’ve got these various Zapruder like memories of riding that, and one of them is seeing the bobcat on the cactus balancing back and forth, or going into Rainbow Caverns or seeing the rocks rolling back and forth. That would probably be pretty dippy to people today.

Don Carson: You couldn’t design that from scratch.

Chris Merritt: Right, right. Yeah, it’s its own thing. Or even dare I say it, Knotts Berry Tales. As much as I look at these beautiful photos we’re going to put in the book and it takes me right back and I’m like, oh my gosh, it was so wonderful, but maybe to someone else or maybe someone who doesn’t appreciate Rolly Crump’s design aesthetic, because Knotts Berry Tales was basically Crump let off the leash to do whatever the f he wanted, which he did do. It’s pretty wacky. I don’t know. I do know I could say something along the lines of, well, yeah, you kids, things were better when they were simpler, simpler back then.

But I got to tell you, Rise of the Resistance is the most, and I didn’t work on that at all gobsmacking jaw dropping attraction you’ll ever ride, and that’s the most complicated thing in the world. It’s like three freaking ride systems jammed into one. It’s amazing, it’s absolutely amazing. So I don’t know if there’s an answer to it other than I just think as a designer, you have to put as much of your heart and soul into that. And then also just like I said before, keep remembering that those other 10-year-old kids who are going to experience it and have their memories with it, that’s a big topic.

Dan Heaton: Well, you bring up a few things. I think about Epcot too. I look back so fondly on going as a eight-year-old, 10-year-old, whatever, and I’m like, do I have too much nostalgia for Kitchen Kabaret or something? It’s so weird, but what I love it if it opened now, and then I think about music too, because I think about my favorite bands. A lot of them are bands that I listened to from 1992 when I was 16 to 1998, and why do those resonate so much more strongly than maybe a band that I discovered two years ago? Some of it is when it hits you. I think it’s a bit of it with theme parks or like you mentioned with movies or anything. We could probably do a whole show on this. It’s complicated.

Don Carson: We’re the emotionally raw in our teen years too. Our young receptors much more open for that when we’re kids.

Chris Merritt: Right. I’ve heard it said that emotionally and in terms of accepting new things, whether it be art or culture or music or what have you, we all have our windows wide open from the time that we’re small children until we hit our twenties and that window starts closing a little bit more each year. And I definitely have to say for me, I was a teenager in the eighties and I’m a big vinyl nerd Luddite, and so for me, my favorite thing is to listen to all my favorite bands from the eighties on vinyl, the way I used to when I was 16, and going to see The Cure, Bauhaus, or New Order or whatever.

That’s still my favorite, my first choice. There’s lots of other bands I like that I’ve listened to. I love Jack White and the White Stripes and just got into Aimee Mann again recently. But I do find, I don’t know if you two can relate to this, but I find every year that it’s harder for me for someone to say to me, Hey, there’s this new band, and check ’em out. And I’m like, alright, I’ll try that. Nine times out of 10, I’m not interested. Just once in a while something will kick in.

Don Carson: That’s a question I was wondering too, is that I remember as a young artist, I would go to bookstores when there were bookstores to go to and I was like a vacuum cleaner sucking up information, and now when I go to bookstore, my wife criticizes me. She said, you only buy books with art that looks like yours. I’m almost really honing in on a very specific aesthetic, and I’ll snatch up a book where someone is exploring something that I’m exploring.

Chris Merritt: Yeah, I’m on a cryptozoology kick right now.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. Well, I mean, I could go on about music from my childhood forever too, but just going back to theme parks, I think that’s, for me as a guest, being wowed, it takes a lot, but I think about riding Flight of Passage and being like, oh yeah, it’s a screen, whatever, and I got on it and I was like, oh my gosh. And there are still moments like that, but I think it’s a little trickier for us now, and I’m sure it is for you. Sometimes something like Rise of the Resistance can blow you away, but it’s that inexplicable thing. You don’t always know when it’s going to hit you.

Don Carson: No. Well, I have fond memories of CircleVision, right? It’s a big circle picture and I’m thinking, VR duh, come on guys, export this file, and so I can see it. I do wonder whether or not it will be worthy as far as the way it depicts America and the music and so on and so forth, but in some ways that’s exactly why I want to see it. I want to be transported back to when I was a kid, going to see that and experiencing it. Sure.

Chris Merritt: I’m fairly obsessed with, and I think this’ll be a book I’ll do of turn of the century Coney Island, particularly Luna Park and Dreamland and the original steeplechase. Before they even get to the ‘20s is too far for me that early, late 1800s, early 1900s.

Don Carson: Before it burned to the ground.

Chris Merritt: That those three parks had, and then all the little wacky attractions that surrounded them. I’m fascinated. I’m completely fascinated. I want to see that stuff recreated in VR so I can jump in my time machine and visit them again. Just even things like if you look at Thompson and Dundee’s, a Trip to the Moon attraction, which was at Luna Park, but was at the Buffalo New York World’s Fair prior to that, that’s the original.

The original, what do you want to say, ride simulation where for your listeners who don’t know the history of a trip to the moon, it’s fascinating because again, this is in the late 1800s, early 1800s, you actually got on a physical ship that would fly you to the moon through the use of theatrical scrims that were on giant rollers that were the size of the Fight of Passage building.

Guys are back there cranking these things by hand to make it look like you’re flying away from Coney Island and up to the moon, and then you actually land on the moon. You actually get off the ship and you walk around the surface of the moon where midgets dressed as a moon man hand you pieces of real green cheese and moon maidens serenade you and you meet the king of the moon, and then you walk out through a moon dragon’s mouth that dumps you backed out into Luna Park. I want to visit that man. I think that’s so cool.

Don Carson: Cool. That was my kind of hope with doing the Alice project, was that I wanted to illustrate just how doable that is, and as an aside and as a future looking sort of comment, is that I’m working on a side project with some friends, and we had a meeting and then we decided we needed to build some models.

And our next meeting, we all met inside the models using Quest VR and a program called V Sketch, which lets you go into SketchUp models, and we gained so much knowledge in our second meeting about which direction we wanted to go in because we walked through six versions of the venue and picked from it the things that worked, and whether it’s the Metaverse or whatever this thing is going to become, the ease at which we can recreate places very much like attraction from Luna Park.

Those tools are available and actually kind of easy to use, and we’re starting to standardize the pipeline for getting them in front of people, if ever you get funding to build that. I’m there with you, Chris. Right. We’ll talk. Yeah.

Dan Heaton: Well, great. Well, this has been amazing, guys. I could do this all day, but I think I’m going to land the plane now. This is fun, Chris. I’m really excited about your book that you’re working on about Knotts Berry Tales and about the attraction for me who doesn’t know that much beyond what I read in the book about Rolly Crump about it. This is really exciting, so thanks for being on the show, and I’m super excited about your book.

Chris Merritt: Great. Well, thanks for having me.

Dan Heaton: Excellent. Well, Don, I’m excited to see what you’re still doing here with VR and obviously the Alice project is great, and I know there’s going to be so much more, but thanks for coming on the show once again. It’s been great.

Don Carson: Well, thank you for having me. It’s always fun.

Leave a Reply