Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

When I think about factors that distinguish the best theme parks from the rest, background music ranks near the top. The best examples create the right sense of place and atmosphere. Some of my favorite places click because of the music. That effective sonic environment helps build a memorable experience. A perfect example is the Innoventions Loop that played at EPCOT for decades. Some of my favorite memories of that park involve hanging out in that space at night. Composer Russell Brower created the music that helped make that area such a cool spot.

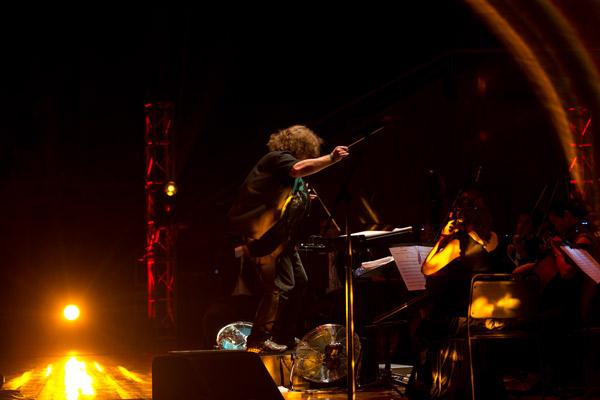

Russell is my guest on this episode of the Tomorrow Society Podcast to talk about his extensive career. He originally joined Disney when EPCOT was still under construction and worked in multiple stints for the company including as a principle media designer and music director. An important early project was collaborating with George Wilkins on the music of The Living Seas. Russell also produced the original soundtrack to Disney’s Animal Kingdom and wrote music and sound effects for Tokyo DisneySea. He’s also a lifelong Disney fan with a passion for the parks and how they work.

Beyond his role with theme parks, Russell has also found great success composing music for video games. His work includes massive games like World of Warcraft, Diablo III, and Starcraft II. He has won three Emmy awards and received numerous accolades for his music. On this episode, Russell compares writing for video games versus theme parks. He also gives advice to aspiring young composers looking to enter the industry. It was great to talk with Russell and learn more about his amazing career.

Show Notes: Russell Brower

Learn more about Russell Brower’s work on the Innoventions Loop and more in this 2012 article from The Disney Blog.

Listen to Russell Brower’s interview on the Imagination Skyway Podcast with Matthew Krul from July 11, 2020.

Support the Tomorrow Society with a one-time donation and buy me a Dole Whip!

Note: Photos in this post were used with the permission of Russell Brower.

Transcript

Russell Brower: We have our first downbeat recording, one of the main pieces of music, and I turn around and I see the designers of the ride, Lori and Rob’t Coltrin sitting back there just giddy as can be because their childhoods are coming, rushing back to them. And just a measure and a half of hearing that music. When it was over, when that first take was done, I was so enraptured, I think I was just kind of frozen with this big stupid grin on my face.

And there was a tap on my shoulder and I turned, and Richard Sherman goes, what did you think of that take? I thought it was pretty good, but what did you think? And I looked at him and I thought, you’re asking me, you, Richard Sherman, are asking me what I thought? I died and went to heaven that day. It was just really an amazing thing.

Dan Heaton: That is composer Russell Brower, who’s here to talk about his incredible career creating music and other sounds for Disney’s theme parks and a lot more. You’re listening to The Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on episode 136 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. I’m really excited about today’s episode. I talked with Russell Brower. He’s a composer who’s been involved with so much – the Living Seas, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Tokyo DisneySea, and of course, a loop that many of us know, the Innoventions Loop. Every once in a while online, we’ll see someone ask the question, what’s your favorite background music loop at the parks?

So many of the answers we hear are this one, which is essentially what played through that middle corridor of Epcot starting in the mid-‘90s when Epcot was redone and then well, until pretty recently where essentially it’s, I find myself going on Spotify and finding David Arkenstone’s Papillon, just so I can hear part of the Innoventions Loop. Of course, it’s on YouTube everywhere, but Russell talks about surprisingly how quickly that came together and then some of the tweaks that were made.

That’s a really cool story, but he’s done plenty more than that going back to the early days of Epcot where he joined to do a very different role and he’s also done work for video games like World of Warcraft and Diablo III and others, and has a lot of cool thoughts about ways that young composers and others can get involved in the industry. So it was really cool to talk to Russell. I can’t wait for you to hear it. I feel like this turned out really well and I had a lot of fun recording this interview.

One thing I really appreciated about this episode; I’ve talked to a few composers like Mark Mancina and Bruce Broughton who are more creating music for films or in a slightly different way. And what I found interesting about Russell too is being on staff at Disney for part of his time, he has a bit of a different perspective of some of the projects he worked on and also how he kind of became a composer. Working for Disney is a really interesting story too. So let’s get to it. Here is Russell Brower.

(music)

Dan Heaton: My guest today is a composer, audio and music director, and conductor for a wide range of mediums. He was a principal media designer at Walt Disney Imagineering and wrote classic parks music like the Innoventions Area Loop, worked on the soundtrack for Disney’s Animal Kingdom. He also created sound effects in music for the Living Seas, Disneyland Paris, Tokyo Disney Sea, and more beyond the parks.; he also has composed music for major video games like World of Warcraft and Diablo III. It is Russell Brower. Russell, thanks so much for talking with me here on the podcast.

Russell Brower: Greetings program, Dan.

Dan Heaton: Oh, thank you.

Russell Brower: A throwback to the Tron days.

Dan Heaton: Yes, I am very familiar with Tron and its music. It’s a great way to start the show, especially given just all the things you’ve worked on at Disney and beyond, but upfront, I’d love to know too, I know you got interested in Imagineering very early on, and I’d love to know what was your background just with Disneyland or your interest in working there even when you grew up?

Russell Brower: Well, I grew up in Glendale, California, so I was a stone’s throw from, well WED Enterprises now known as Walt Disney Imagineering, and I didn’t know that for years, but that was really nice to be close by. And Disneyland was only 35 minutes away and my parents and I went at least once a year and it was a very special event and it imprinted on me very young.

I remember when I was nine years old for the very first time, I took a tape recorder with me and I brought the sounds of the park home with me and not just the rides, but the clip clap of the Clydesdales on Main Street and the various area entertainment and things like that. And in listening to this over and over and in subsequent trips, making other tapes of specific things that I wanted to remember, I was learning about storytelling.

The same thing was happening as I watched Warner Bros. cartoons on television. I was learning about comedic timing and things like that. And I think all this just was absorbed as if by a sponge, by me over the years. I had this strong interest in, well, first of all, working at WED Enterprises and I was willing to do anything there, but of course my interests were rapidly coalescing around music and sound and storytelling with those as a principal medium and living in the same town certainly made it convenient as far as being a young person and going to work there.

But getting to work there was really hard. I had to really kind of kick and scratch my way in. I told my career counselor at my high school at Glendale High School that I knew where I wanted to work and first she had to get up off the floor.

She’d never heard any student tell her that before. As it turned out, just kind of by luck, I guess like an ex-roommate of hers or something like that, was an assistant to Tony Baxter, who back then was just kind of in the, I’d say Big Thunder Mountain was maybe within six months of opening. And anyway, these people graciously arranged a tour, which Tony himself graciously arranged to host.

So by this time I’m in high school and I’m getting a tour of WED, and it was just the most amazing day of my life up to that point. And Tony gave me that tour and well, I was persistent over the next couple of years and I managed to get into a summer hire program where you basically just got anything randomly that you were assigned to do. In my case, they knew I had some background in school in architecture and mechanical drafting and things like that.

So they put me in a department where I was helping to check blueprints and things like that. And this was in 1981, and we were in the home stretch of Epcot and I got to work on a little of everything from the Glendale side of things, and thus began just always working at WED whenever I possibly could. I had about four tours of duty there eventually going full-time a couple of different times and focusing more and more on music and sound and, and then in the times in between I got to dabble in television and toys and video games and other things.

Dan Heaton: I mean, it’s interesting how everyone just kind of has a similar story where there’s a little bit of chance or luck involved with getting to work at somewhere like WED. And you mentioned working at Epcot. I mean that time from what I’ve heard was just really busy and a little manic and everything. What was that atmosphere like at Epcot when you first joined there, just given that, I mean, they were working towards the opening date the next year.

Russell Brower: Well, again, my experience was all from the Glendale side, but it was definitely an exciting time. I remember a few months before I was working my first job ever, and it was a local clothing store called Miller’s Outpost in a mall in Glendale. I think I was there over the holiday season, and that was probably, that would’ve been the 1980 holiday season.

And I remember while I was working in that store, there was an ad on the radio that they were playing through the PA system in the store that said, we are hiring for Walt Disney’s last and greatest dream. And they talked about Epcot. I was just, I’m sitting there folding jeans and I’m like, oh, if only, if only. And fortunately it was about a year later that I did manage to get that first summer gig, and it was crazy; it was all hands on deck.

It was a wonderful first job because I saw what I think humans do best when they’re rallied around one really inspiring idea, an idea that’s been a long time in coming has been refined to keep up with the times. It was no longer going to be an actual city, but it’s now going to be more like a permanent world’s fair type deal. And when that many people, and by then I think it had peaked at around maybe a couple of thousand people working at the company and for Epcot and Tokyo Disneyland were going on at the same time.

So that made it even more crazy. And I worked on a little of that too from the just checking blueprint side of things. But most of my first work I consider to be on Epcot. And it was real exciting. I think one of my most vivid memories is of opening day, and they brought a big satellite edition to the parking lot, which was kind of unheard of on that scale in those days. It all was very exciting, all this technology to experience the opening simulcast live on the WED campus in Glendale. And to do that had to get there real early in the morning. remember the ceiling was completely covered with helium balloons. You couldn’t see the ceiling at all these special figment lavender balloons everywhere that said, we did it on them.

I remember standing in the warehouse looking at a huge projected screen of the live coverage from Florida, and I happened to be standing next to the head architect, and his name flies out of my mind right now, but he was the chief architect of Epcot and probably kind of nearing retirement age at that point. We happened to be standing next to each other when the opening ceremony happened. And all these Walt Disney World Entertainment trumpeters were standing on the inner edge of the roof of CommuniCore on all sides. On both sides. I think they were talking about having 76 trombones or something, and they’re all lined up on the very edge of the roof there trumpeting during this big event. And I happened to glance over to the architect and he had gone white as a ghost.

I said, are you okay, man? And he goes, the roof isn’t designed for that, pointing was a shaky hand at the screen. He’s like, they’re not supposed to stand there. And his head was in his hands. Anyway, as it turned out, everyone was okay, nothing bad happened. So it was just kind of a funny memory, but he was quite beside himself that he had never meant for 70-something people to stand on the edge of the roof.

Dan Heaton: That’s really funny. And it just shows how they were going all out for this big celebration. There’s somebody who’s like, Hey, wait, wait, we didn’t know about no one gave us the memo basically on that, I guess.

Russell Brower: But it was a good visual and it turned out okay.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it all worked out. There were no tragedies involved with that. Well, you mentioned that, I know you started looking at blueprints, but then you got more interested in working with music and sound effects and everything. So what was that like? When did it really start to sink in that that’s what you wanted to do as a career early on, beyond what you wanted to work at WED, but then you wanted to eventually be more of a composer?

Russell Brower: That switch flipped for me during my next job at WED. And I had been working on doing some mechanical drawings and just anything that was needed, I thought to do some model making. I mean it exciting then if you had the aptitude to do something at wed, you were allowed to do it and you were encouraged to do it, and if it moved the project along, you got to do it.

So yeah, a little time in the Model Shop. I remember when I was listening to your Joe Harrington podcast and he was talking about meeting Harriet Burns and Claude Coats and people like that. And I had that same experience just meeting my heroes, and I was completely getting sucked into it and loving it. But then there was this point where for this new project, this project that was called the Tron Arcade, it was a post opening, probably opening sometime in ‘83 in the CommuniCore area.

This was a project that never ultimately came to be in that form. It ultimately was reborn years later as DisneyQuest, but that back then it was in CommuniCore. And so I got this gig working on that, and there was this point in back about mid-‘82 where that project really needed some music and some sound effects as proof of concept. We were creating games, it was going to be the arcade of the future, hence why it was called the Tron Arcade. So it was going to need these sounds.

But the whole sound department of WED was mostly, they were all in Florida doing final installation and test and adjust on Epcot. So there was no one to do it. That was the point where I kind of thought, huh, maybe my out of control hobby, like I was spending every minute of my non-working at WED life on learning to create music and sounds and building and learning to play synthesizers as an instrument.

I was devoting all my time to this, and I saw an opportunity, so I asked, may I contribute to the sounds for this? The person in charge said, well, if the sound department doesn’t mind, then sure why not. We know you want to do this kind of thing. And that was a general attitude around Imagineering back then, or WED Enterprises back then.

So they asked the Sound Department and the Sound Department, they knew me very well because I had been walking around roaming their hallways after my job was over for many weeks, getting to know the various people and picking their brains and frankly learning a lot from them about sound production. So they knew who I was and they said, well, okay, yeah, why not? As long as anything Russell does is not heard by the public at this time without our express approval, he can do, sure, he can do mockup stuff, knock yourself out.

So I got to do that, and I suddenly was getting paid in the dream factory I’d always wanted to work within and be a part of, and I was working with what I really loved to do. I was creating sounds, I was writing some little musical backgrounds for some of the games and working with my various colleagues to solve technical problems on how the sounds would be actually delivered to the guests in an interactive fashion. And it was also exciting. The second I got to do that, that’s when the switch flipped.

Not only, I mean I just realized this is what everyone means when they say, do what you love and you worked far too long in your lifetime to do anything other than what you truly love. I never really looked back after that, and I stayed with, and I did music whenever I could. That’s a little harder to get your foot in the door, but I managed by the mid-‘80s to do that professionally for the first time. And actually my first professional musical work was for WED.

Dan Heaton: That’s great, that really you were able to have that opportunity because I’m sure if they hadn’t, who knows what would’ve happened that they gave you a chance to do that? You mentioned two mentors, or you mentioned people that were kind of legendary people at the time. I know that for music for Epcot Center, two big figures of course were Buddy Baker and George Wilkins, who I’m so interested in that all the music they’ve done for a lot of those early pavilions like Horizons and World of Motion and so much more. So I wonder too, they were involved so closely with music if you had much interaction with them or they had much influence on what you were doing then.

Russell Brower: Well, they had every bit had all kinds of influence over me before I even knew who they were. In all honesty. I mean, Buddy Baker since before my birth has had an influence on me. Between him and George Bruns and the Sherman Brothers, there are some total of my early musical heroes right there. I remember during the Epcot years, I remember seeing Buddy Baker in the hallway once. And I was just too starstruck and I just kept going and he looked like he was on a mission, so I didn’t bother him.

But I did see him in the hallway, and I knew of George back then. I think we had met a couple of times, but where I really met George was a couple of years later when I found myself working for the company that created the Teddy Ruxpin talking toy. George was brought in to be the musical director and composer of that project.

That’s where I then worked with George on a near daily basis for several years. And after influencing me from afar for many years with his work on Epcot, suddenly I was basically just with him every day. And there’s no better way to learn than to be with in a working situation alongside someone who is a master at what they’re doing, and you just absorb it all and it’s just a wonderful thing. I definitely consider him a mentor as well as a dear friend, and he’s the one who gave me my first musical job for anything, and I am eternally grateful to him for that.

Dan Heaton: You mentioned George, just he did a lot and it’s great. You also got to work with him, which I know a lot of former Disney imagineers and others worked. I believe that was Ken Forsse’s company that did Teddy Ruxpin. It’s interesting how many people I’ve talked with that were involved that all were working there in that time after Epcot.

Russell Brower: Well, again, there was a big shrinkage of WED after the opening of Epcot. I was very fortunate, and my move into music and sound is actually what allowed me to stay on about a full year after Epcot opened, which is more that I could say for some others. I was incredibly fortunate that I got a bit of an extension to my time there. But if you think about your Disney history, you’ll know that by ‘84 for sure, early ‘84, that’s when things were getting really janky there in terms of rumors of takeovers and things like that. And ultimately that’s when Michael Eisner and Frank Wells came in and re-energized things.

But yeah, so after everyone found themselves outside of WED, several really amazing companies were formed during that time, or various people ended up joining up with companies that were fairly new at the time. And I found myself at Alchemy II, which is the Teddy Ruxpin company that was formed by Ken Forsse, who also worked for WED for many, many years. And while I was there, everyone from Bill Justice to Leota Tombs came through and helped out on projects. So I still felt like I was in the club of old Disney folks.

So that was great. And then of course, that was when I really got to work closely with George, and George was still working on Disney stuff as it came up. Once things started picking up again after Eisner and Wells joined, and it was in ‘85 that George gave me the Living Seas exterior background music job, which was my first big break musically.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I’m such a fan of the Living Seas. I went a lot to Epcot as a kid, so I would’ve gone to see the Living Seas when I was, I dunno, around 10ish or so, maybe a little after that. And that music and just the water hitting the front and just that whole vibe of the outside and then the pre-show is just so cool. So I’d love to learn a little bit more just about your experience on such a cool project.

Russell Brower: The Living Seas means so much to me because in that tour that Tony Baxter gave me back when I was in high school, one of the things he showed me in the then titled Epcot presentation area within the big warehouse at Imagineering, one of the models he showed me was of the Living Seas, and this was the version with the big animatronic of Triton.

I remember of all the pavilions that he showed me, that was the one that excited me the most. I loved it. And I swear to you in that moment I thought, wouldn’t it be great to write the music for that? And of course, I’m just a kid in high school at that point thinking just dreaming. I didn’t say that out loud, but so about four or five years later when it actually came to pass, it was really meant a lot to me.

George helped me a lot. He wrote the main theme and he sat with me one evening and he played it for me on his piano and told me the ideas he had for the extended loop. And then he pretty much let me do it and expanded out to an hour and provide, and I wrote some additional themes and some counter melodies and a few things to stretch it out to the whole hour.

But the idea of having the sounds of the way of the kind of, not crashing ways, but the rolling title forces and stuff and the whale songs, I’m not quite sure if that was an original idea that they wanted me to do or if I came up with it. So I won’t claim it since I don’t know for sure. But it was such fun to do and it was the very epitome at the time for me of storytelling where that music, as you approach the building and later as you leave it and even while you’re inside it, it’s sort of like the glue that keeps constant through your experience there.

Whether it’s literally my recording or whether it’s George’s theme that appears in other forms in some of the other little module shows and things like that, it shows you how beautiful a musical environmental experience can be and how much it can add to the storytelling in the mood of a place when someone of George’s wisdom makes a master plan for the whole place and then casts two or three other folks to work with him to realize it all. It just has this, it’s the kind of guidance I imagine Walt having given to his Imagineers when they were building the original Disneyland, and he’s the one that has the big picture in his mind.

George had the big musical picture in his mind and what a privilege and what a learning experience and what a positive start for me because the music business is full of ups and downs, and there would certainly be some less cheerful musical and political experiences in the future. So it always is wonderful to make the first one out the gate be something that charges you up and keeps your motor running for a long time.

Dan Heaton: Totally. And I love the idea too, of that original pavilion, the way that they, like you mentioned storytelling, the way that it led you through the walking pre-show and then the film and then the Hydrolators and then the Sea Cabs. There was so many steps that there was a lot of planning involved to make, and the music played such a key role in that for sure. It all just connected really well.

Russell Brower: I appreciate that. And again, a huge, huge bunch of that belongs to George because again, he had this master plan and it really influenced me as I grew in my career. Then later on when I had the chance to be in his seat in the musical director’s seat, it’s affected everything I’ve done since then.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I can imagine. And I want to jump ahead a little bit, but still since we’re in Epcot in Future World, I know when you have kind of the open-ended question that people always ask, like what’s your favorite background loop, especially people that have been fans for a long time, one that comes up a lot is that Innoventions Area Loop that played through Epcot in the center area for so long. And I know that you were involved with creating that, so I’m just curious. I know people would love to hear just how that came together to ultimately the music that so many people have known for so long.

Russell Brower: Well, I appreciate that. It’s one of the things I am most proud of. And yes, that was maybe my first chance to apply everything I learned with George without George being in that spot to guide me. And I got a call from Don Lewis of the Sound Department, and he told me about this need for this new track, and I think enough time has passed that I can probably tell this story and not get myself or well Don in trouble, but the story goes like this. It might be apocryphal, I don’t know. Don told it to me, but apparently Don was walking through Future World with the show designer for that space for the ‘94 redo when they added the tensile structures and made CommuniCore into Innoventions and things like that.

It was just about two weeks before it was going to open, I think, or soft open, and Marty Sklar was with ’em. And while they were walking through the original Epcot medley that George put together, and I learned so much from just by listening to it ever since 1982, that music was still playing. I guess Marty looked over at the other guys and said, you’re going to have some new music for this opening. They said, yep, Marty, you bet.

Fortunately about that time in the mid-‘90s, there was this time where I would get called, I’m not ashamed to admit it. I get called sometimes when there just wasn’t time to call anyone else. And so they called me and said, this thing opens in two weeks. Can you do a track for it? I of course said, sure. That was the theme of this whole thing. Just say yes and somehow it will happen.

And of course, it was a little unrealistic to get full buy-in from everyone at that time. So the first thing I did was I looked for some third party music that I could run by them to see what they’d like. I had spent a lot of time in the previous days walking through the model of the new area. They had rebuilt a little Spaceship Earth model with the tensile structures and everything as a scale model at Imagineering.

So I spent about an hour just standing in the middle of that model and staring at it and soaking it in and remembering being there and trying to remember how I’d want you to feel. I’d want you to feel one way walking into the park and then another way as you walk out of the park at the end of the day, tired. But suddenly all these musical ideas are now familiar.

You’ve seen everything now, and so there’s more resonance as you leave the park at the end of the day, and I just wanted to have this whole cinematic experience from the beginning of your day till the very end. So I thought about it and I thought about it, and I went through some third-party music and ran it by the show design. His name slips my mind at this point who was working with Don Lewis and myself.

But the piece of music that they liked the best, and frankly it was the one I liked the best too, was this David Arkenstone piece called Papillon, which is I know one of the other ones that people love because there is a version of that track that still plays out there, or at least it did. I’m not sure what’s playing there now, but that piece of David Arkenstone’s ended up being kind of the vibe and sonic, kind of like a model sheet for an animated character.

This is what the character looks like from all angles and all that. These are the proper colors and stuff like that. Well, this piece of music was sort of the blueprint for it. So I did that, and when I selected that piece, then I went and spent about, I had about a day and a half that they allowed me and I put together counting the Papillon piece.

It was about nine and a half minutes of music, and that’s what I could do in the day and a half that was left by the time that everyone had agreed on the direction and everything like that. I did nine minutes, and that included my main theme, which I call the future world theme that some people think sounds best in the restrooms, but that’s a whole another podcast and it does sound best in the restrooms. Anyway, I put together that nine and a half minute thing in my mind, it couldn’t stay that way for long.

I mean, by 1994, I had been going to Epcot a lot. I mean, I had been either to work or as a tourist for, I’d been there probably a hundred times by then, and I knew what a day at Epcot was like, and in my heart I knew that that track should be an hour and it should quote the other pavilion music thing just like George’s original did, even though we were trying to do something that said something new for the whole approaching the millennium and the whole Epcot 94 or Future World remake and everything.

But I wanted some of that kind of old school approach still kind of snuck in there. So there’s a lot of homages in my version to George’s original Epcot medley and both to the texture and the blowing wind and the wind chime kind of a thing and things like that. I tried to do a similar thing so that it would still feel like Epcot to folks who were returnees, but would also be a nice support to what was new there and to the new story that was being told.

So in a very short period of time, it was only about between 10 and 12 more days, I did my final version, which was an hour long, and that’s the version that I always wanted to play there. And it played there sometimes and it always played in other areas in some areas of future world depending on where you stood in one corner of mouse gear and things like that.

But there was this weird conflict that I ended up having with the show producer whose name probably fortunately I can’t remember at this point, because he said, no, no, no, no, I don’t want an hour of music there. He said that that area around the fountain and where it’s playing, he said, that’s a thoroughfare. People don’t stop there. We don’t want people to slow down there. We want people to keep moving. And I’m thinking, no, I had learned a long time ago, you kind of stick up for your idea and explain once and you have to read the situation whether it’s okay to do that, but you kind of say, this is what I was thinking. And then if they say no, then it’s no. Well, he said no.

He insisted it be a thoroughfare, and he liked my main theme. So he had me cut out everything but my theme and the Papillon piece, and it ended up being like this 20-minute loop of my theme in all its various forms and then the David Arkenstone piece. And that was there for a while. But then I got hired on in end of ‘95 full-time and became a media designer. I think somehow my long version eventually got installed again somehow.

Dan Heaton: I think though, one of the great things about that is that it is a lot of the great background music tracks is that you come in at different times and you hear a little bit here and a little bit there, and sometimes you are just hanging out because the worst is being in wherever, some park or somewhere and it’s a five-minute loop and you just keep hearing the same thing in a line and you hear the same thing over and over. I think it’s great to just catch little pieces of it because it’s there to set the right mood, and you kind of always want more when you’re hearing it.

Russell Brower: Well, I think if you choose to sit and cool your heels for a while, and I think of people, I think of grandparents waiting for their grandkids who they turned loose for two hours, meet us back at the fountain at four o’clock or whatever, they’re going to sit there for maybe 30, 45 minutes, or more. If they choose to the music most of the time, 99% of the time just washes over them and is doing its job.

They’re not necessarily noticing it, but for those who choose to notice it, I wanted to take ’em someplace. I wanted to take ’em on a journey. We did the same thing. I worked on all the opening day music for the Disney/MGM Studios, and each of those loops were an hour, and each one was a mini lesson on the musical history of the movies with various central themes depending on where you were in the park of ideas or whatever, adventure music over here, romantic music over there, what have you.

So yeah, later on I did feel that what the show producer who felt that the music should be short in the middle of Epcot, I just felt he was wrong. And later on when I could influence some change there I did. Then later on when I worked further later on when I worked on Animal Kingdom and ultimately Tokyo DisneySea, I just kept up with that philosophy. Frankly, they still do long form BGM to this day, and I like to think that I helped make that popular. I don’t think for a moment I’m the first to ever do it because Epcot itself, opening day was the first to ever do it. That was Buddy Baker and everyone else.

But I think there was a time where after Buddy had retired and George had retired, that I think some people might’ve forgotten what the power of the background music was. I just had it in my head that it was this ideal storytelling opportunity, and that’s what Imagineers do. I think they influence where they can and add all sorts of little delightful things for people to discover when they go back or take some time to pause or what have you.

Dan Heaton: And I think that it makes a big difference in setting the field a part. And I have seen that with some recent additions, like a Pandora or something where the background music really helps like it did for Epcot. Speaking of the Animal Kingdom too, you just referenced that. I picked up a while ago, the CD that came out, which I know you produced, which was a lot of the music that was from 1998. And I find that there are very few groups of music.

None of them are really, I wouldn’t say there’s, I’d say I love track six or track eight, but they all create this overall mood of that park and fit so well, putting that together, or even just in general for DisneySea or wherever, how are you able to figure out what works for a certain land or park when you’re dealing with something as big as like the Animal Kingdom, which could go so many different directions?

Russell Brower: Well, Animal Kingdom was unique in that Joe Rohde and his core staff had traveled all over the world for literally years gathering the artistic and story backgrounds and cultural guiding information that would ultimately become Animal Kingdom. Joe very much loves and champions music. So he came back from those trips with literally suitcases full of CDs and cassettes from all kinds of regional music from all over the world, and certainly all the places represented in the Animal Kingdom. he had me listen to all these things that he had collected, and he told me what he liked the best and things like that. So that one was unique because it was, except for around the Tree of Life and Oasis Gardens and maybe a couple of other areas, it was all pretty much music that was found and procured from all over the world.

Dan Heaton: That’s really interesting. I wouldn’t have expected that because it fits so well in the park. But knowing what I know about Joe Rohde, it doesn’t surprise me just given I know they spent, I mean that park’s development started in 1990, ‘91, you can see it in the park. The fact that they spent so much time being able to build that idea and that theme where it wouldn’t have been possible if it had a quick turnaround.

Russell Brower: Absolutely. Yeah. In some ways, Animal Kingdom is, I think Disney’s most beautiful park. It’s certainly its most detailed park. It’s the one that you can spend, I think the most time getting delightfully lost in those details and learning something along the way. And while some of it follows some of Disney’s own original storytelling, there is an awful lot. Everything in the Animal Kingdom that looks authentic, it really is. I mean, and Joe can show you slides of the real prototype of whatever it is you’re looking at, where they saw it somewhere in Africa or something. Similar with the music, he was talking to me about what music, when they let their ears guide them down a side street toward something that they were encountering some local musicians doing something.

I think they did a little amateur recording of some of this just for fun, but we didn’t, none of that was used. But he would play though. He would say, oh, I heard a couple of percussionists and a guy with some kind of squeeze box doing this thing. And he goes, and it wasn’t the type of, it wasn’t the style I expected to be in this area, and it just blew my mind. It was so cool. He’d show it to me and oh, he was so excited about it all and it really comes through in the park.

Dan Heaton: Oh yeah. I mean, I’ve found that as I’ve gotten older, whereas especially when I was going with young kids, it was like I was less focused on I want to hit 20 attractions or whatever and more just walking around the park slower. That park benefits more from a slow stopping looking around, I’d say pushing a stroller. There’s a lot of things that you see in here in that park that you would not see if you took it like a super fast touring or anything else. It’s really something. And I know DisneySea is that way too. I have not been to DisneySea, but I’d love to hear at least some info too about that experience for you, given just how cool and amazing that park looks.

Russell Brower: DisneySea was definitely a great privilege to work on, and in no small part because Disney’s partner in Japan, the Oriental Land Company, they wanted a no compromises top drawer experience. It’s not that there were no limits, there were absolutely budgetary limits, and there was definitely what you would expect of the usual iterations where things were changing for all sorts of reasons.

Some of them financial, but in the end, they definitely had their eyes on their goal was to have no compromises park. It’s so beautiful, and maybe it certainly, and it gives Animal Kingdom a run for its money, in part because there’s so many more hands-on guest or closeup guest areas. I mean, Animal Kingdom is large in acreage, but DisneySea has so much guest area that has this incredible level of detail. It was also a privilege because almost none of it had been done before.

And that was really exciting. I feel very fortunate to have rejoined the company at a time where I got to have a hand in pretty much all the background music for the park. Then as far as music within attractions and things like that, as a media designer I was assigned to had two mysterious island mainly, and a couple of other areas, and various things changed here and there over time. But that’s when I got to work with Buddy Baker. He came out of retirement to work with us on the Aladdin attraction and also other things that were coincidentally going on.

I brought Buddy back to work on the Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh that we were doing for Disney World at the time, and all that was going on at the same time, so quite a hodgepodge. But DisneySea gave us an opportunity to create both music and sound effects for a near life-size volcano. Highlights for me were the 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride and the Journey to the Center of the Earth ride. Those were both completely new ideas, or at least 20,000 Leagues was a new take on an old idea. And Journey was definitely unique to that park.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, both of them, I mean, again, I’m only looking at it from online videos and other people that I’ve talked about it, but both of them, I’m just so baffled in a good way. I’m just look at the ride system like 20,000 Leagues, the idea that you think you’re underwater, but you’re not really, and all that. The sound, I’m sure plays such a key role because they have to sell this adventure that is not exactly similar to the old 20,000 Leagues, but even more to the degree, it’s a different setup completely.

Russell Brower: It is. And actually having listened to your Joe Harrington podcast, I used a technique I learned from him, and that was when choosing where to put the speakers inside each ride vehicle of 20,000 Leagues, I had put, there are two large speakers inside the vehicle that handle the sounds of the engines. And I put those both in indirect patterns where one is actually under a central seat facing the floor, and so the sound is blossoming off the floor and just rising up and filling the cabin.

The other one is back behind you. And what looks like kind of an access, it actually is the emergency exit hatch in real life that you never use, hopefully. That speaker is in there also facing the wall, and the sound has to bounce off about three surfaces before it hit you. So it makes the engines feel.

We built the engine sound based on the original 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea reactor sound from the film itself. The Jimmy McDonald’s all slowed down electro, I think it’s actually a de goer, a demagnetize hum that slowed way down makes that Nautilus thrumming deep motor sound. So that plays out of those speakers and the sound bounces off the walls and kind of surrounds you.

And as memory serves, we have a total of 14 speakers in each ride vehicle so that each little alarm sound is localized and we have sounds supporting the bubble windows so that as you’re seeing these kind of glycerin bubbles floating up around you, the sound to support that is coming from as close to the right location as possible. There’s several speakers to eliminate the point source effect. It wants to sound like a wall of sound, not like a point of sound. And again, things I learned from Joe, bless his heart.

Dan Heaton: Well, Joe, yeah, he’s just from my time talking with them. I mean, I did not understand everything because he’s just, the guy’s brain is working on almost a different level, and I mean that in the best way possible.

Russell Brower: Well, I remember when he was talking about the LCU local control unit and stuff, some people might’ve been saying, now, wait, what was the middle part of that one? But in a sense, the company was transitioning from sound delivered over some kind of bar along the track that’s electric and carries a sound with some brush picking it up and something that would snap crackle and pop and sound terrible. The company was transitioning from that to solid state sound that’s not being transmitted or picked up. There’s no danger of a radio signal dropping out or a bad electrical connection, and there’s no moving parts. So unless all power fails, chances are the sound will keep going.

And while 20,000 Leagues was not a high impact environment, the system was developed originally for the roller coasters and stuff. So where vibration is definitely a thing. So yes, he was describing that transition. When you think of all the TV specials you’ve seen with the big computer reels of tape spinning back and forth and waltz explaining how this is running, the whole Tiki Room attraction or the small world attraction off these alternating reels of tape, that system one in one form or another still existed in the parks all the way up through it was in transition in Epcot. I mean, in original Epcot, they were still using a of that, and those were all being phased out by the time we were getting into the ‘90s.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I mean, I think about just the changes and how things work and where it was when I was going, and I would marvel that early Epcot and how everything worked and you felt like the sound was on your vehicles. But again, it was something like Horizons where it was like there was a little deck on your vehicle that it was not, and I’m describing it terribly, but there was not an easy way to do it the way it was now, and just really impressive.

I’d like to finish Russell with just some overall kind of larger questions before we finish. One of them of course is that I have to mention like I did at the intro, your work on World of Warcraft and so many big video games, because you played a big role in that industry and it was a big part of your career. But I’d love to know too, just we’ve talked for the whole time so far about your work on theme parks. This is the simplest question ever, but what are some of the differences when you’re creating for a game experience versus creating something that’s going to be in an attraction or a park?

Russell Brower: Well, people usually ask me, what is the differences between a video game and a movie or a television score? And I’m glad you’re asking me about games versus theme parks because game versus theme parks are very similar. If you think about it, it depends on the genre of game. But if you take World of Warcraft as an example, much like a theme park, you’ve got a relatively free ranging audience that can go pretty much anywhere it wants, and every person in there has their own sound experience.

They’re not hearing exactly the same perspective that even the person standing next to them in the game is hearing just because you might be three feet over to the left and the sound mix you’re hearing depends on where you’re standing, how close you are to a sound source. And even though the sound sources in the game are virtual, they are assigned in a location much like a speaker would be placed in the real world.

The beauty of the video games though is unlike the age old problem in the theme parks where the best place to put a speaker is probably also the best place to put a freaking light or just some piece of architecture that no one wants sullied or something like that in a video game, speakers are invisible and have no mass, so you can put them anywhere. And so that’s great. But I have to say Imagineering was an incredibly rich and prolific and applicable training ground for me working in video games.

I think the reverse could have been true as well, had I, in fact, a lot of people today might actually find themselves working on a video game before they find themselves working at Imagineering. But I think it’s a very strong correlation between, with the kinds of problems that as a sound person you need to solve as a storyteller through music and sound you need to solve, choosing how to start a piece of music.

Is it started by a virtual trip wire or is it started at a certain point in time relative to when you entered to space? I mean, there’s just all these choices to make and where the sound comes from and how many sound sources you have, and how literal you’re going to be versus how cinematic you’re going to be and things like that. So there’s a strong correlation between the two. Whereas with linear media like film and television, I still think storytelling is storytelling and there’s a lot of similarity. However, because it’s linear and it’s fixed, there’s just a whole lot less you have to worry about. And in fact, in linear media, it has its own charms. That’s because hopefully the music will be mixed to an ideal level in the overall scheme of things.

Once it’s set at that mix level, that level hopefully won’t ever change. And once you get the perfect mix of, I won’t say Star Wars, they keep changing that, but once you get, say, the mix you hear of your favorite movie one day is probably not going to change much the next time you see it, if at all. But at the parks, there’s so many variables, things can change. So yeah, there’s a lot of commonality in storytelling and whatnot. There’s some different technical challenges with linear versus 3D theme parks or video games or virtual reality, things like that.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s interesting because yeah, I always would think it was very different, but you bring up a good point, especially with video games now where it’s not a similar, a Super Mario Brothers, or I’m making a really old person reference, but something that’s has a theme and just continues because it’s so, it is similar in a lot of ways to a theme park. And you mentioned too young people who may be working in both industries.

That kind of leads well into kind of another question I had, which is if someone’s aspiring to become a composer or work in sound, or even some related field in theme parks or entertainment, I’d love to know just from your experience, if you have any guidance or advice you would give them as they’re figuring out what to study or even what approach to take as they get moving.

Russell Brower: I would say that find out who you’re a fan of in terms of their work and study their work. I feel like there are so many possible styles and things like that, that it’s really hard to become a master of all of them. And if there’s something that you feel like you’re the best at, I am not saying that people should stay in their lane and never get out of them. I’m just saying as much as you would tell an aspiring writer, write what you know, or you’re going to have the most depth in writing something that a lot about, I would say that if a certain genre speaks to you, definitely see if you can go with that.

It’s hard to get a career going, and I’m not even sure how I would start now, except I would say that networking is everything I would suggest any composer who’s looking at making a profession out of it, I would suggest joining something like the Society of Composers and Lyricists and disclaimers aside, I’m on the board of that organization, so I am biased. But there’s that, if you’re particularly interested in video games, there is an organization called the Game Audio Network Guild, which is similar to the Society of Composers and Lyricists, but is only focused on video games, and therefore their video game network is especially rich.

But if you’re interested in going transmedia and being involved in theme parks and films and television and basically across different genres than something like the Society of Composers and Lyricists is maybe a little bit better fit. The point is that these are organizations that are just dedicated to resourcing for newcomers into the field. It’s dedicated to sharing knowledge and keeping the excellence up in these fields. These aren’t unions, they’re more just professional organizations of folks who want to not keep reinventing the wheel and do want to further the art. There are great ways to network, and in this day and age, you no longer have to live in Los Angeles or New York to have it be worth your while.

You can actually, now there are virtual events we have certainly, it’s not just that we have Covid to thank, but we just have the Internet and modern technology to thank that so much of the archives of say, conversations with composers who are no longer with us. Maybe like someone like David Raksin talking about how he came up with the theme for Laura or you can watch this wonderful interview where he talks all about it and it’s things that can never be replaced.

Now so many of these people are gone. So yeah, network, learn, look for a chance to maybe work with a competitor. One of the best things that happened to me was when I got hired on the Teddy Ruxpin project, I was hired because I could do some sketch work and I could do sound work, and I had some fantasies of writing the music, but I wasn’t remotely ready to do that in my career yet.

I just didn’t really know that yet. But when George got hired, the cool thing is I got to be next to the guy who got the gig and while applied his magic and created all these wonderful songs for Teddy, I got to see what his thought process was like and things like that. So I tell people that if you’re going out for a gig and you don’t get it potentially, especially when you’re kind of new in your career, see if you can get a job with the person who did get to get it, because then on, I hate to put it this way, but on their time, you can mentally imagine how you would’ve done. And of course, while I was watching George make his magic on Teddy Ruxpin, I was thinking, oh man, I would’ve died 10,000 times.

I was not ready. And actually, I don’t really consider myself a songwriter. I’m more of a soundtrack score writer. I do melodies, but I don’t do lyrics. So I never would’ve been right for the Teddy Ruxpin music, but what a privilege to be there for every session and to watch George make decisions. And it really served me well. And then years later, I found myself on a scoring stage with Buddy Baker at the podium. I’m at the producer’s desk and Richard Sherman’s sitting to my left for the Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. And of course, I’m in heaven, and we have our first downbeat recording, one of the main pieces of music. I turn around and I see the designers of the ride, Lori and Rob’t Coltrin sitting back there, just giddy as can be because their childhoods are coming, rushing back to them.

And just a measure and a half of hearing that music. When it was over, when that first take was done, I was so enraptured, I think I was just kind of frozen with this big stupid grin on my face. And there was a tap on my shoulder and I turned, and Richard Sherman goes, what did you think of that take? I thought it was pretty good, but what did you think? I looked at him and I thought, you’re asking me, you, Richard Sherman are asking me what I thought are his take.

And I died and went to heaven that day. It was just really an amazing thing to be around these heroes of mine. And I’m so grateful to them for sharing their time with me and their stories and memories with me. And I’ve been very fortunate to have a little piece of that magic in my own career over the years. So I’m really grateful for that.

Dan Heaton: Well, I think that story is amazing and it’s a perfect place to close the podcast. But thanks so much for being on. I’d love to know if there’s anything you’re currently doing or if people want to find out more about you or your work, Russell, is there anywhere they should go or I’d love just to know your current activities.

Russell Brower: I have some social media presence on Facebook and Twitter primarily under my name. I’m easy to find, please look me up. And I would say I’m working on a couple of things I can’t talk about yet in kind of a low key way at this point. But what I’m most excited about in all honesty, is I realized I’ve been working for nearly 40 years and every note I’ve written has been in service of a theme park or some game or something. And it’s gone into that project and it’s a wonderful thing, but it wasn’t like a hundred percent my own thing. So after 40 years, I think I finally deserve it, my opportunity to do my solo thing and just express myself musically.

So people who have enjoyed my music at the theme parks or have enjoyed what I’ve contributed to the video games like World of Warcraft and whatnot, if they like that stuff, I think they’ll like my solo work. It won’t be too far off base. In fact, it might even be kind of the soundtrack to a theme park that never was. When that becomes a little bit more concrete, I would love to let you know. And of course I’ll say something about it in the social media and whatnot and encourage, just encourage people to check out that music whenever I get it across the finish line.

Dan Heaton: Well, excellent. Yeah, that sounds really exciting, and I’ll be excited to hear it for sure when you have it ready and keep an eye out for it. Well, thanks so much, Russell. This has been a great interview. I love a lot of the music you’ve created for the parks and more, and really enjoyed talking with you. Thanks a lot.

Russell Brower: It was my pleasure, Dan. Thank you so much for having me.

Leave a Reply