Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

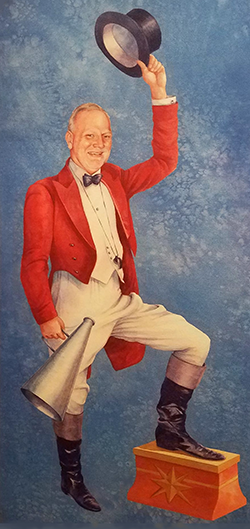

A love for trains played such a key role in Walt Disney’s life and the creation of Disneyland in 1955. It’s no surprise that a similar passion continues to inspire designers that have worked for Walt Disney Imagineering. A perfect example is Ray Spencer, who brought that interest for railroads to his work at Disney. He worked as a consultant on entertainment and theme park projects before joining WDI in 1997. Those early projects included large-format films, the Mystery Lodge show at Knotts Berry Farm, and jobs for Universal and Disney.

Ray joins me on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast to talk about his career at WDI and beyond. We discuss his roles on Soarin’ Over California and Turtle Talk with Crush before diving into his key project as Creative Director of Buena Vista Street. Ray describes the goal of creating a comforting entrance with a real sense of place for Disney California Adventure. He also explains the concepts for the Storytellers statue and Red Car Trolley, which both help to enhance this attractive space. Another cool project for Ray was the change from Condor Flats to Grizzly Peak Airfield. We talk about how those updates help the different parts of DCA flow together into a coherent whole.

This episode also focuses on the updates to Big Thunder Mountain Railroad at Disneyland. Ray explains the significant changes that go well beyond the new finale effects. They ultimately rebuilt the Rainbow Ridge setting while keeping it aligned to past versions in the park. Ray’s passion for railroads made this a special project for him. He also provides some advice at the end to designers hoping to become Imagineers and work on theme parks. I really enjoyed the chance to talk with Ray and hope to have him back in the future and dig further into his great career.

Show Notes: Ray Spencer

Listen to the recent episode of the Thunder Mesa Limited Podcast with Ray Spencer.

Watch Ray Spencer talk about the inspiration for the Red Car Trolley with the Orange County Register.

Note: Photos in this post were used with the permission of Ray Spencer.

Transcript

Ray Spencer: And then I wanted every corner at that hub to be activated. So we have the shops on one side, we have the Storytellers statue and the department store, Elias and Company. On one corner you have Carthay Circle Theater on one corner, and then the Trolley stop on the other corner. So you’ve got a lot of places for people to hang out and the fountain in the center, which was modeled after a couple of LA’s period fountains. So there’s a lot of places for people to sit and watch and meet and gather and take pictures. And it was super important to me because that’s the comforting grounding thing. You can do anything else in any other land, but if you’re not grounded, if you don’t have a place to get grounded, then you’re just going to kind of aimlessly wander around.

Dan Heaton: Disney Imagineer Ray Spencer is here to give us all the background about what went into Buena Vista Street and all the various aspects of the redo of the entrance to DCA. You’re listening to the Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Hey there, thanks for joining me here on Episode 154 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. Hope we’re all doing great. I’m really excited to bring you this new episode. I talked to former Disney Imagineer Ray Spencer, who worked for more than 20 years at Walt Disney Imagineering, and one of his biggest projects was the overhaul of the entrance to Disney California Adventure.

He was closely involved in every aspect of Buena Vista Street, including the placement of things like the Storytellers statue, the Red Car trolley, Carthay Circle, everything involved with that, and he digs into it. And also the updates to Grizzly Peak Airfield from Condor Flats and the reasoning behind that and how that fits better. What I really connected with here is the talk about making it a grounded, like you said in the intro, pleasant place to hang out.

Because I think about places that I love at theme parks, a lot of them are not the attractions, they’re just spots that feel right when you’re hanging out in that area, whether it’s in Harambe, in Disney’s Animal Kingdom, whether you’re just walking down Main Street at Disneyland or elements of World Showcase, Pandora, so many other places that just feel like they fit inside the park.

There aren’t any visual contradictions and there’s that reassurance that has been talked about so much with the Disney parks and I think that’s definitely true at Buena Vista Street. Ray also talks about his work on the updates to Big Thunder Mountain Railroad. Ray is a big railroad enthusiast, so this project was really important to him. Also updates to Turtle Talk with Crush, Soarin’ Over California a lot more, plus his story and what ultimately led him to work at Imagineering.

I feel like this just scratched the surface. So I definitely hope to talk to Ray again in the future. This was really cool for me because I haven’t done that much on DCA, especially on the DCA updates. So to dig into this, this was a corner of the history of Imagineering and the parks that I haven’t really spent much time with. So hope you enjoy it. Let’s do this. Here is Ray Spencer.

(music)

Dan Heaton: You’ve been involved in just so many interesting things and even that list I just gave, just really scratch the surface, but I’d love to go back well before you were working at Disney and everything and just how’d you get interested in just being in this industry or even becoming an artist and working on entertainment?

Ray Spencer: When I was growing up, my father was an artist and I used to watch him paint and I’d watch him draw. He’d do these fantastic things with meticulous detail and he could take something and in two strokes of a brush make it look like something. It was like magic to me. I’d say, how did he draw a wheel with just two little strokes and all of a sudden it’s a wheel? I mean, he would do these things and it was magic to me, and that kind of stuck with me.

So from the artistic side, I think he may have had a lot more natural talent than me. I put in a lot of hours learning how to draw, I mean thousands of hours. When I went to school, I ended up majoring in industrial design. I liked architecture and I liked technical things and I liked all that stuff, but because I was able to draw, I could express ideas quickly for things that didn’t actually exist.

I could do a sketch and somebody would say, oh yeah, I get it, blah, blah, blah. So from that, while I was in school, there was a number of people that had gone and actually were, as students were working in entertainment, they did get picked up by film companies to do concept designs for spaceships and all kinds of things. I liked all that stuff as an industrial designer, designing toasters and waffle irons, irons and hinges and things like that. It’s okay, but it didn’t really light my fire. So I found that with my drawing skills, the kind of fantasy thing of drawing things became more interesting to me. And then fantasy environments interested me as a kid. I went to Disneyland of course, and Knotts Berry Farm had a ride called the Calico Mine Ride, which was really influential on me as a kid.

I don’t know if somehow it resonated going down there and riding that ride and being in this really immersive, wonderful environment that was fantasy. Later in my childhood, before my college years, our family went through a rough patch and I was looking for anything that would kind of take me out of that and give me a sense of being someplace different, someplace exciting and wonderful, and I don’t share that with too many people.

But at the same time, I think it influenced me to sort of help push it forward to others. So when I had the opportunity to do some concept illustration for some entertainment attractions, I took advantage of it. Of course when I first started out, the pay was peanuts and I was scrambling to do anything and I did, and I found that it was a good fit for me. So that’s kind of how I got started in this business.

Dan Heaton: I think that makes a lot of sense. You mentioned the Calico Mine Train, which is such a cool attraction. It’s still involved, and I know you’re a big enthusiast of trains. Speaking of that and which obviously has a lot of connections with Disneyland and with Walt and everything. So I mean, how much do you think that led you into just being interested in the industry or even like you said, this kind of world of fantasy that got you interested?

Ray Spencer: That’s a good question. I mean, I think it really did, and I’ll give you a couple reasons why. Well, first of all, I’ll back up a second. Walt Disney was a big influence on me as well. I mean, seeing him a wonderful world at Disney on Sunday nights and seeing Walt, he was kind of like the father or the uncle or the family that you really would like to have. He was a very safe and comforting person to a lot of people that would watch him and get inspired by what he was doing.

The educational aspect and the enthusiasm behind the fantasy was something that a lot of us really looked forward to as he was still alive at the time I was a child. But I mean still, it was like this was meaningful to a lot of people and me includedThe train thing when I was a kid, I spent a lot of time in a small town in Nebraska and the small town in Nebraska had a brick main street, and at the head of that main street was a brick railroad station.

Trains would come and go and to a kid, to a 7-year-old, which is really when I started paying attention to it, seeing those trains come and go and they’re going to wonderful, marvelous romantic places in your head and they’ll bring you back safely. I think the metaphor for Main Street and the train station at Disneyland was the same. There’s something about safe, about being in a hometown, having this vehicle that can take you to wonderful places and bring you back safely, and there’s a comfort to that. And I think the train thing, I always liked them.

My grandfather was a locomotive engineer, so it kind of rubbed off on me from that aspect as well. But the train thing just seemed right and it just resonated with me. Then moving forward as a kid, being interested in that stuff to building models of them and creating these environments, these little cities and towns, that’s kind of a fantasy thing. So yeah, I mean creating environments, trains, theater, lighting, it all kind of is a part of that my life and the trains are a part of it.

Dan Heaton: Definitely. I think that’s the case with a lot of people, especially like you said, growing up with Walt on the TV and just how much the trains were such a big part of, and just transportation in general with Disneyland and everything else. You mentioned too that you ultimately started taking on jobs early on, and I know you worked before WDI, you were working for a long time as a consultant and working on a lot of different projects. So how did that kind of progress as you went along and what were some of the types of projects you did back then?

Ray Spencer: Interestingly enough, when I started out, I started working for film special effects companies basically. So there’d be sketches of an effect or something that would happen and blah, blah, blah. I draw this stuff and there was model makers and people doing the practical effects, and I learned a lot about kind of film and how it was put together through that.

Then as a tangent to that, there was one company in particular that was doing motion simulation films and sort of pioneering the whole sort of simulator industry. So I got involved with them and started conceiving different types of ride films where you’re telling a story in three or four minutes. And once I started doing that, then I found that the community was a smaller community than one would think that, okay, I’m doing this for this person and then somebody else comes along and it’s an attraction and I’m drawing this and doing that.

Then that was gig work. So it would be project by project. And it didn’t take a whole long time to really get ramped up and get a steady workflow going at that time. But it was back for me, it was the sort of late-ish nineties maybe, I mean eighties, excuse me, that I really started getting going. So that’s when I had the opportunity to work for some of the companies, for instance, Universal or BRC Imagination Arts and others. I had some really great projects with really great creative people and really great experience to work around in this and related industries.

Before I joined WDI, because I had the opportunity to do small projects with a small budget, I had the opportunity to do larger projects with a small budget. I had the opportunity to do fantasy projects as opposed to sort of museum and visitor center projects.

So I think I had a lot of opportunities to see different points of view and different ways to approach design and how storytelling works in that environment and how people move around. Starting with the film stuff, that was really good training for me because if I think about our guests as a camera that has a free will, you’re thinking about where they’re looking, where they’re going to look, what they’re going to look at, what’s important to look at and what’s not important to look at.

So thinking about people as cameras, it was helpful to me then I could plan the scenes and the shots and understand what they’re going to see and what they’re not going to see. That helps. That helps a lot. Like I said, I think it is really important to me too to make, I have an aspirational view of this stuff, which is you want people to feel better at the end of the day and they may not know why, but if you can help create a little bit higher sort of consciousness and a better feeling and camaraderie among human beings, I’m all for it.

Dan Heaton: And I think it’s pretty common that a lot of people that ended up in Imagineering and those types of roles worked in the film industry, especially given the time period. I’ve talked to a lot of people that have done that, and I think that’s a great example, just like you said, where the theme park is this film come to life. I love the way to think about it as us as I haven’t heard that before while we’re going through when we’re doing it, it’s a fun way to think about how theme parks kind of function in a way for us as guests.

Ray Spencer: And everything tells a story, whether it’s the story you want to tell or not, everything tells a story because if you’re looking at something, let’s say a Disneyland and you’re looking at something and it’s wonderful, and then you turn around and you see the gate open, there’s all these trash cans and all this crud going on, that tells a story too. It’s like that stuff behind the gate that I don’t want to see. And you just destroyed my fantasy. Thank you.

Dan Heaton: That’s not what we want. So as you started to progress, like you said in the late ‘80s had picked up and whatever, what were some of the favorite projects or favorite things you liked to really work on that kind of built up as your career grew during that time?

Ray Spencer: Well, I like projects that are based in some kind of reality, not necessarily exclusively, but I enjoyed working on one project in Florida, Kennedy Space Center. I worked on the Apollo Saturn Five show for BRC Imagination Arts at the time. I like having some reality and then adding drama to reality and pushing it so that people can kind of feel the magnitude of what they’re seeing. And I enjoyed that. And another one I enjoyed was Mystery Lodge at Knotts Berry Farm, which I’d worked on. That was based on a show that was at an Expo in Vancouver, Canada. And I forget the year that was ‘88 or something like that called Spirit Lodge.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I think it was ‘86 I think is when it was, but right around that it was the last North American Expo basically.

Ray Spencer: Yeah, and I’d heard about that show because it was really kind of pioneering and people really responded to it. So when Knotts decided to do a version of it, I was fortunate enough to be working with the company that produced it, and I was very happy to be able to participate in that as well. Just the technology and the effects and really understanding the, I don’t know, I think I learned a lot about storytelling as well on shows like that. For me to back into the reason for the art and to understand why we do the things we do and why it’s important to do this and that. I mean, it took a while. I had to think about it.

It’s like when I taught school, I had to take what was intuitive to me. Like, oh yeah, you put the red here and you put the blue here, or you put the vanishing point over here and stuff that I wouldn’t necessarily think about, I would just do. Then I had to go back and quantify it and say, why did I do that? Well, it’s because you want a composition that works and you want people’s eyes to go here. I had to learn that by doing it. A lot of these projects helped me do take a lot of those steps to be able to do my work at Disney.

Dan Heaton: Those are both great examples, just with the Mystery Lodge is just its own thing and the best way possible, especially for a park like Knotts. I love that that was able to be there. Then Kennedy Space Center, you mentioned reality to bringing the reality to life. I can’t think of almost a better place that does that, especially given a lot of people like myself, Apollo was before I was born, so to be able to bring that to life had to have been just, that’s such a great place to do that.

Ray Spencer: Yeah, and I’m really happy I had that opportunity. And the subsequent developments there, the shuttle simulator and stuff like that was long after I was gone, but it was great to see them continue with that storytelling.

Dan Heaton: Well, ultimately you did end up joining Walt Disney Imagineering in 1997. So how did that end up happening where you ultimately went from being someone that might do a project to actually working full-time for them?

Ray Spencer: When you’re a project hire, a project by project basis, you’re kind of thinking down the road like, okay, who haven’t I talked to? Where do I need to go? And I talked to my fellow designers and fellow creatives and somebody suggested to me, you should go to Walt Disney Imagineering and talk to them. So unlike some people, I really didn’t know a lot about Imagineering. I knew that some people regarded them as sort of the pinnacle or the holy grail of design opportunities, but I didn’t know a lot about them.

So I got the number and the name of, I’m not sure, I know it was the creative department, but it was the kind of gatekeeper of talent, and I got the number and the name. So I called and I made an appointment to go see her. And back in those days that was, I don’t know, early ‘90s, maybe mid ‘92, ‘93, something like that, which doesn’t seem that long ago, but it’s a long time ago, relatively speaking. And back in those days, you have a big portfolio full of stuff. You’re not toting around a tablet or a thumb drive.

You’re not just sending it a reel on virtually. But I went in and I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t know a lot about the place. So I went in and I had a portfolio of stuff and we kind of leafed through it and I thought, okay, well that probably went okay. So then she sent me to see somebody else, and then that person sent me to see somebody else. I thought, well, this is probably a good sign because I’m being sent around to see different people, so this probably is a good sign.

So ultimately, I finished making those rounds and I didn’t really hear anything. Every month I would call or I would write or whatever and say, Hey, is anything available? Do you have anything coming up? I’m interested, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. One day they called me and that was after about a year of silence.

They said, we want you to come in and work on it, some Epcot projects, and we’re going to have you come in for three weeks. Because I think at the time they like to test you out. They’re not going to say, okay, you’re going to come on for three years. It’s like, we’ll have you come in and then after three weeks we’ll probably have an idea of what your skillset is and whether you’re a good fit and blah, blah, blah. So when I started, honestly, I was terrified. I thought, okay, I’m going to go in there. There’s going to be a bunch of hot shots here. Everybody’s going to draw circles around me. This is my own insecurities coming up. Of course they’re going to be super organized.

So I go in, and that was exactly not the case. It was just regular people doing regular stuff. And when I saw the state of the project that I was assigned to, I thought, well, okay, this is really blue sky. I mean, this isn’t even note cards on the storyboard. It’s like people just sitting there talking. And at first I thought, well, what am I supposed to do? Why am I here? I guess I’ll just roll with it and see where it goes.

So while they’re talking, one skill that I have that I really worked hard to foster was quick drawing because what I found is in design and things like that, if you can get something up on the wall quickly as people are talking, it leads to either a binary thing, which is, yeah, that’s a good idea, or no, that’s a crummy idea, or it gets a project to kind of another point.

There’s value to that. And I realized that. So at Disney, I just started doing these quick sketches. So then after two or three days they said, well, we’re going to yank you off of this and put you on another project. They put me on another project, and that little three-week assignment turned into about a year and a half solid of consulting work at Imagineering. And that was full time.

Because I felt like, okay, with all my contacts and all the work I’ve been doing, I have all my eggs in this basket. I don’t think that’s probably the best idea. So I kind of weaned myself away a little bit from Imagineering and kept doing some other stuff. Meanwhile, as I was working on this, that and the other, they actually asked me, do you want to come on board as an employee? I said, well, I’m not quite ready for that yet. But actually when I started working on Soarin’ at California Adventure, which was in the late ‘90s, I thought, okay, this is an opportunity to see this through to opening day, and I think I want to do it, and I have small children at home, so I think I’m going to get a real job. So that’s when I hired on.

Dan Heaton: It’s a good reason.

Ray Spencer: But I was flattered that they would consider me, and I was flattered that an organization with that kind of prestige and talent would have me on board. So I was happy to do it.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. Well, Soarin’, I mean, that’s a great project to be on, especially, I mean the original sort of California at the time, now there are many flying theaters, but was pretty novel. And also I talked to Rick Rothschild about it, who was involved with it, and it just sounded really interesting. I mean now there’s a lot of things you could do with CGI and everything, but this was all practical all out there shooting. I know you worked as an art director and content designer. So what was the experience on Soarin’ like for you getting dug in for such a cool project?

Ray Spencer: Well, it was interesting because I had worked back in Massachusetts on some projects and actually in the same studio they were doing Back to the Future: The Ride, they were doing the film for that, for Douglas Trumbull I was working for and seeing those miniatures, I was all done with miniatures and in-camera effects and all kinds of crazy stuff. And that was before the days of CGI. Seeing the tests and seeing the projections in the domes and understanding cross reflectance of light and all that stuff, it was really interesting to me to work on Soarin’ because I knew that I had a little bit of experience with that medium. Even though it was all kind of live action and cuts, so it was fun.

It was a lot of fun. I worked on primarily the show design. So if you look at the queue, you look at the way the architecture works, you look at the way it transitions from sort of early corrugated metal to modern materials, there’s a whole sort of transition that happens and a whole thing in the pre-show and the queue. And that was all pretty much my baby. The film part of it, I didn’t have much to do with. I did some early storyboard sketches of some of the sequences, the first scene flying over Golden Gate Bridge and some of the other stuff. And then yeah, we did a few sequences of that and some concept art and that was it. Then I did the design for the pre-show and the theater.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, well, especially in California, I feel like even just the exterior, but then you get into from there to the pre-show and everything, I think does a really good job of setting the right mood of early aviation and everything else. And I hadn’t really connected that as much. Back to the Future, I think of that more as Star Tours, but a lot bigger. But there is a lot of similarities.

The more I think about it, the way you kind of lift up in the air and there’s the big dome and it’s like you’re moving. It’s a lot more similar than I would think actually. And Back to the Future. Incredible. Especially like you said, doing that, what they did, I saw something fairly recently with the model, the miniature dinosaurs and how they did that is just crazy to me.

Ray Spencer: Oh, it’s crazy. And Back to the Future, they had to calibrate each one of those cars, so their point of view in the dome was slightly different. So you didn’t have some crazy perspective thing that makes you sick to your stomach. I mean, there’s a lot of science that goes on in that kind of stuff, so you know where you are and you’re not carsick all the time.

Dan Heaton: And Soarin’ over California I feel like is one of the best at that where people, I know people that have motion sickness that can do that just fine, that gets sick in a car. It’s weird how that’s done so well with that almost. It’s crazy to think about how much went into making that feel the way it does.

Ray Spencer: Yeah, it is. It really is. It was a great experience. I really, really enjoyed it. Appreciate I could be on it.

Dan Heaton: Oh yeah. And I know another one you worked on early on or fairly early on was Turtle Talk with Crush, and I know you were also involved with some other elements of the Seas there. Again, another thing where I feel like now seems pretty standard but was very novel for the time. So what was your role in that end? How did that go?

Ray Spencer: Oh, Turtle Talk really, again, it was me taking an existing space and shoehorning this theater in there with a rear projection and all the technology they had to produce. And so for me, I was more into styling of space as opposed to production of media. So although I was appreciative and happy to be involved in the media production and discussions, that wasn’t my thing. My thing was more the environment. Once we did it there, then we did it at California Adventure. So I did that one as well. It’s a great show. I mean, it’s just like you said at the time, it was sort of a pioneering thing where you have a live, interactive, real-time communication between kids and adults and

Dan Heaton: Well, the first theater that you had to put that in, I mean designing the space was very small. I remember going to it before they moved it, and like you said, it was not a space designed to have that attraction. So I’m sure there was a lot to that.

Ray Spencer: And at the time we did a shark exhibit called Bruce’s Shark House in an adjacent space, and that was challenging as well. It really was kind of shoehorning these shows into these spaces, but I think it worked out pretty well. And then subsequently they moved it, like you said.

Dan Heaton: Well, I want to make sure we spent some time on one of the biggest projects you worked on, which was being a big part of the overhaul of Disney California Adventure and its entrance and Buena Vista Street and a lot else. So I wonder just upfront, how did you get started on that project and what were kind of the origins for you that led you into such a big role for it

Ray Spencer: Since DCA 1.0 opened in 2001, I’m sure many of your listeners are familiar with the park and sort of the postcard entrance that it had, and it had a big sun icon in the hub, if you call it that, called Sunshine Plaza and some other stuff. But it was kind of the anti Disney Park in a way. I mean, it was irreverent and maybe kind of poking fun at itself. And it did not have any Disney characters. There weren’t any walk around characters.

It kind of took the DNA of a Disney park and set it aside and said, okay, well since Disneyland has that DNA, then we’re going to do something that doesn’t have that DNA and it’ll be a different experience. And for a lot of reasons, a lot reasons that didn’t work out so well. It kind of bugged me from day one because I worked on that park, I worked on Soarin’, I worked on the winery, I worked on the wharf, and I worked on that park and I had some really good memories and some cool experiences, but the DNA of a park just didn’t seem to be there.

So almost immediately I was doing sketches of what could you do to warm this place up and what could you do to kind of make it feel homey? And I didn’t know the exact things I was looking for, but if you think about John, his book the Architecture of Reassurance. Reassurance is, for instance, Main Street. It’s comforting to people to know when they enter the park that they know where they are, they’re on this nostalgic street and it’s warm and it’s romantic and it’s friendly and they’re safe.

It’s a great place to get grounded before you go to these different areas and have your different experiences. And DCA did not have that. You go in, you kind of don’t know where you are. I think people had a hard time understanding that. And so it seemed like it would be good to start grounding this in something that was more comfortable and really had that DNA because it was clearly not particularly well attended.

There were some issues. I was always dabbling in that, and there was other people dabbling in it. And the management at the time, there was no appetite for making any changes because changes are expensive. Then really dealing with some of the issues that were challenging, it requires a lot of introspection and stuff like that. And so really when Bob Iger became president of the company, then that door kind of opened a bit.

So I think he realized the value of creating a Disney Park and creating that DNA and the accountants couldn’t make sense of it because you’re not adding attractions, you’re not adding a bunch of merchandise, you’re spending a lot of money to change the look of things and the way things feel, but you’re not increasing capacity. So when you can’t justify spending money to do something like that, some people say, okay, well we can’t do it because it’s not going to make us any more money.

But then there’s some people, and I think Bob Iger was one of them that said, well, you know what? You make a great people are going to come, they’re going to spend more money. The word of mouth is going to be great, and the park’s going to be that much better and we’re going to deliver a Disney project, so let’s go ahead and do it. And it takes that kind of leadership, I think, and commitment that he had to help do what we did in 2012 to the front of the park and cars land and that sort of thing.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s one of the things that I, beyond attractions that I love about theme parks too, is they just are so comforting as a place to hang out or a place to be. And you think about the best areas of Disneyland or even World Showcase or Animal Kingdom, wherever. It’s so cool. So how important was it when you were developing Buena Vista Street to make it that kind of relaxing place where someone can just go and be rather than running to Soarin’ or running to Cars Land?

Ray Spencer: It was at the top of my list. It was at the very top of my list because if you think about a hub, say for instance Disneyland, you’ve got corners off of the different streets that intersect the hub, and those become people, places where people gather and either there might be a restaurant there or there might not be, but there’s a place for people to gather and to hang out and to just be comfortable and to energize the space. And also it takes the pressure off of all the attractions to do that function.

So it was super important to me because I still have original chicken scratch sketch of the first layout of that street, Buena Vista Street and how the hub that has the fountain, it’s not lined up with Buena Vista Street, for instance, Disneyland the hub at Disneyland, and the Castle lined up exactly in the same line as Main Street here.

We didn’t do that because I kicked the Hub off center because we don’t have a berm like Disneyland. You can always at California Adventure, you can see out of the park at Disneyland, you can’t because there’s a berm with a railroad station and it blocks your view. You don’t look outside and see people milling around at the ticket booth. So first of all, we had to create some isolation visually from the entrance.

So the hub got kicked off center, but the Carthay Circle theater is not off center. It’s still in line with Buena Vista Street. So you have that icon or that weenie at the end of the street, as Walt would call it. And then I wanted every corner at that hub to be activated. So we have the shops on one side, we have the storytellers statue and the department store, Elias and Company.

On one corner you have Carthay Circle Theater on one corner, and then the trolley stop on the other corner. So you’ve got a lot of places for people to hang out and the fountain in the center, which was modeled after a couple of LA’s period fountains. So there’s a lot of places for people to sit and watch and meet and gather and take pictures. And it was super important to me because that’s the comforting grounding thing. You can do anything else in any other land, but if you’re not grounded, if you don’t have a place to get grounded, then you’re just going to kind of aimlessly wander around. And so I thought that was really important as we developed that.

Dan Heaton: You want to have a sense of place, and like you mentioned, you come in and you immediately go, oh, this is a nice place to be. This place feels like you said, comforting and everything. And just also has a specific era like you mentioned the storyteller statue with a younger Walt and Mickey, which I think was important because also that fits with Carly Circle and with so much else. So why do you think that was so important to have that statue added there in that area?

Ray Spencer: Well, one of the original concept plans, it was placed at the front where kind of by the trolley stop there at the front of the, just past the turnstiles. But one thing that was important to me, and if you saw the sketch, the original sketch I did of that statue, if anybody else saw it, I probably would’ve been fired immediately because it was so bad.

Dan Heaton: I don’t believe that.

Ray Spencer: But it took a sculptor to really, really make that come to life. The thing about the statue is that if you look at Partners statue over Disneyland, he’s up in a planter on a pedestal with Mickey and Walt’s holding his hand up like this, saying, I’m giving you this park. I’ve realized this street, blah, blah, blah. Well, that’s a monument to somebody who’s no longer with us.

So if you did the young Walt, and this story of Buena Vista Street was the next second part of Walt’s career, which is if Marceline, Missouri influenced Main Street, Walt’s hometown, then Walt comes to California from Kansas City in 1923 and he’s in LA, he’s on something like Buena Vista Street. He steps off the Red Car, he takes the train, he arrives at La Grande Station in Los Angeles. I’m kind of backing up for a second here.

He steps off the train with his cardboard suitcase and 40 bucks in his hand. He’s looking around, probably saw a Red Car because the Red Car served the train stations. But he’s standing there and everybody’s walking by him and nobody knows who Walt Disney is because he’s just a young man who’s standing there. And so it was important to me to put him on the ground and make him touchable so guests could touch him and be next to him.

There’s no error of superiority or monumentalism. It’s here’s a guy who has a dream and he realized his dream, but he’s just like you and I, because he’s standing on the ground here, so maybe you can realize your dream too. Putting him on the corner there just seemed like a neat thing to do and that’s why he moved. And plus you get just pragmatically, you get the better sun angles for photography on that corner. So that was, that’s important.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that’s a great point about it being down to earth though, because it’s easy, especially now that Walt has passed for, so it’s been a long time, 1966. I mean, that’s a long time. So a lot of people almost look at him, he’s not a real person, he’s this legend, he’s this icon. But then you show the guy, and it’s totally different than the idea of him as this all knowing person that everything was like a legend, not a real person

Ray Spencer: Yeah, that was the point, really.

Dan Heaton: Well, you mentioned the Red Car too, and I think the Red Car trolley is very interesting too, beyond being kind of a fun transportation system, but it also adds, what do you think that adds to have that red car there in that space as just another touch to the area?

Ray Spencer: Well, if I take point of industry, none of the architectural facades on that street, none of them were real buildings in Los Angeles as opposed to Hollywood Boulevard. When you turn the corner at DCA, all of those buildings are representing real buildings that you would’ve found in Hollywood. We had eight architects working on those, creating each with a different hand and a different point of view. So they’d have a little bit of variation from one to the other. And then Coulter Winn, our lead concept architect did a great job with that.

We had 500 different types of custom tiles on the buildings. We had a lot of stuff that was handcrafted, so it would give it more of an authentic feel to what the textures and materials might’ve been back in the twenties and thirties. And the Red Car was part of that too because at one time, the Pacific Electric Railroad in southern California had a thousand miles of track.

It went from the ocean to the desert to the mountains. That’s how people got around. And so iconically, if you look at photos from those times, even Hollywood premieres on Hollywood Boulevard back in the forties, you’d always see a red car in the picture. You’d see these theaters, but a red car would be coming down the street. So it just seemed like if we could get that iconic front view of that car and just have it a piece of that kinetic, the kinetics that we don’t have a railroad going around the park, but we do have something that can move people around and add to the kinetics that Main Street has through the vehicles and the horse-drawn trolleys and things like that. This was just kind of our version of that, and we were able to do it. So thank goodness.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s not to the level, but the “world on the move” idea where whenever you have the Monorail or the old Tomorrowland had so much of it, but just the idea of things are happening. This is like a lively place, I guess.

Ray Spencer: Yeah, the only thing that it is kind of a non-sequitur is when you have the Los Fila Street Bridge there and then a Monorail goes over it.

Dan Heaton: But they totally connect, but I like it. Another change you worked on at DCA was when Condor Flats was speaking of Soarin’, switched to the Grizzly Peak Airfield. And I’m curious to know a little bit about that change, which to me, it does align things really well.

Ray Spencer: That was interesting because it was coinciding with Soarin’ Around the World as well. I don’t know. I guess I’d have to look at that more carefully just in terms of a timeline. But the theaters were down getting digital projectors at the time, as I recall. And with some of the issues at Condor Flats, and I worked on both of them. I worked on Condor Flats as well as Grizzly Peak Airfield.

So it’s another opportunity I had to not do it once, but do it twice. The original conceit of Condor Flats was High Desert Airfield test pilots, Right Stuff, rockets, things like that. And the inspiration for the building, there were actually hangers at Edwards Air Force Base that was like test flight centers back in the day. But there was two things happening there. I call it warm and cold. It was warm because it was super hot.

I mean, in the summer there was no shade and just a lot of steel and concrete, and it was hot. So it was a warm place, but it was cold from an emotional point of view, a lot of steel, a lot of concrete. So it had two things going on. Really to me, guest comfort in the shade issue was big. And when we looked at it, that runway, if you look down the runway from the hub or from the entrance, thereby what was known as Taste Pilot’s Grill, what you see in the background is the Grand California Hotel, which is a big craftsman hotel that’s green and brown.

It looks like something you’d see in Yosemite, yet you’re in a high desert airfield. And then if you look to the left, there’s grizzly peak and there’s a bunch of pine trees. So it’s harder to tell a story in that backdrop.

And the thought was, okay, well maybe this should be integrated into Grizzly Peak, the airfield, and maybe we have the opportunity to get some shade and some comfort in here. So as we worked on that, it just sort of evolved. I mean, a lot of it had to do with paint and a paint palette and redoing the landscaping, redoing the hardscaping, meaning all the concrete and all the stuff that you see changing the storylines for each of the facilities there, the shop and the restaurant, making it a more human scale because human scale is kind of the handshake, and when you kind of lose that scale and that handshake, it’s a little bit distancing for some people.

Plus the opportunity there at Grizzly Peak was so well done that the opportunity to kind of extend that national park and the warm fuzzies that people get when they travel and take their families to these places and experience nature, it seemed like a good fit. So that was kind of the genesis of that. Once again, it just took a commitment dollar wise, because we weren’t adding anything. We were just changing everything. So do you want to spend a lot of money to change everything? Well, you don’t have to, but if you see that the value that you create is going to be greater than just dollars and cents upfront, the value is going to pay for itself in other ways. And I think that was the motivating thing there.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I mean, that’s important though. It’s hard though. I know to, like you mentioned, the money to sell the ROI or whatever term you want to use of that, because it’s easy to say, well, we got an attraction, people go to it, that’s fine. But it’s so unique having the Grand Californian right there too, and finding a way to connect it. But the benefit, I guess, is if you do, then you have this really cool area that’s also got this amazing hotel as a backdrop, which you probably don’t get in a lot of places.

Ray Spencer: No, and the thing is, I mean, we pulled some of the colors right off of the hotel and brought them into the airfield. So you’re creating a larger environment just by changing colors. And that was a good move, I think. Then there’s a lot of green and brown, a lot of national park colors there, but there’s a little bit of difference to them from facility to facility, so it’s not too monotonous. And then we changed the background music. So the background music for the overall land is more sort of big country, big theme, great outdoors, sweeping, sweeping or orchestral music. And then each facility had its own little soundtrack. So the Smoke Jumpers Cafe there kind of becomes this home spun, I called it Bakersfield Country with the Twangy steel guitars and that kind of home spun sort of country music.

Then we put in a station wagon for representing the road trip of the ‘60s, and we put an old Rambler station wagon, which we refurbished and put a canoe on top and a bunch of camping gear inside. If you listen carefully there, you’ll hear, you’ll kind of the popular music of the sixties that your grandparents may have listened to or somebody way back in the day. But it’s fun to listen to. It’s fun to kind of around and get these different flavors that are helping to tell a little story. And so next time your guests are there, yeah, go by the Rambler, put your ear up to the glass and you’re going to hear some fun.

Dan Heaton: I’m going to write myself a note to remember to do that right now. Oh man. There’s so many of things you worked on. I know there’s too much to cover, but I want to ask you about one more project here, which is, I think it’s related, which is you were able to do, I mean, you were able to do a lot of different updates as part of Disneyland’s Diamond celebration.

But I want to focus on one here, which is Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, which I think kind of relates to what we were just talking about, where you were involved with new lighting and figures and sets and effects. I would love to know for you coming in to make that update, what were some of the biggest goals or what was the approach you really wanted to update or change as you were going in?

Ray Spencer: When I started working on that, that was not originally a WDI project. That was a Facilities project because they were replacing the track, they were replacing all the track and the entire attraction. So all the old track had to come out and all the new track had to be designed. And by the time they redid it back in 1979 when the attraction opened, back then people were drawing drawings on paper with pencils and drawing track plans with pencils.

Probably, I don’t know exactly how they developed them, but I think it was all sort of mathematics and best guess. Well, by the time the track was replaced at that update, that was in, I don’t know what year it was, 2013 or 11, I don’t know when it was, but it was all done with computers. It was all done digitally. Computers were drawing the tracks, they were figuring out all the angles, all the curves.

They were figuring all that stuff out. And probably mathematics could make it kind of a smoother ride and less jarred and abrasive, which is good. But by the same token, it’s the wildest ride in the wilderness, so it needs to have some kind of quirkiness to it. So that was one thing. But when I was called in to work on that, the entire Rainbow Ridge town was being rebuilt because it was so damaged from termites and weather and time that it was just destroyed. I mean, it’s very unsafe and not in good shape. And some of that stuff goes back as far as the Mine Train in Nature’s Wonderland.

So it was time. So all of that stuff was scraped and rebuilt. And so I was there to keep my eye on that and make sure that was done. But also, I had done some sketches too, of how we might plus the final scene there.

And at one time, the finale in the ride was on the third lift hill, which is, they call it lift sea. You go up the lift, something happens, you miraculously leave the mountain and then go back to the station. Well, at one time it was an earthquake, and there’s these big sliding rocks that were on hydraulic grounds. It would slide down toward the track, and then you’d see a projection of rock falling up above you. And because of an incident with the rocks, there was a real concern about safety. So they were locked off.

So there really wasn’t a threat or much to look at in that final scene. And so my interest in not only trains, but in the west and mining and turn of the century stuff, I thought this could be a fun opportunity. And so we went in and we did some phony dynamite fuses and tried to create the idea that here’s a place where dynamite’s going to blow, and you got to get out of there.

So atmospherics have a lot to do with it. There’s some practical fog effects, and then there’s some other strobe effects, and there’s video projection and projection mapping. There’s a lot going on in that final scene. And if all the conditions are right, if you’re there at the right time of day and all the things are working right, and the temperature’s right, you’re going to get a great show. But there’s all those variables, you can get a different show from ride to ride.

And that was one that I worked on that it just took a lot of planning too, because the ride you get from the front car is very different from the ride you get from the last car. It’s a different physical experience. If you’re trying to create a show, it’s a very different experience because while somebody, for instance, on the final lift, somebody might be on the front car at the top of the lift, well, you still haven’t even started the lift and you’re in the rear car. So how does this show affect you as you go up there? So we did a lot of experimenting, and the timing is something that literally I had to sit in the train at different points in the train and night after night, ride it for 15 or 20 laps.

It was just quite a deal because sometimes I’d have to pop a Dramamine and then just plop myself in there, and then we’d ride around. Then you’d say, okay, advance the explosion half a second, and then you’d get in the back car and you, well, that doesn’t work. Okay, advance it. I mean, it’s just stuff like that. You could do it over and over and over and over again, and then hopefully you hope for the best show. And also when I was working on that, I wanted to keep it credible because it’s really easy to think of the Old West and just do slapstick kind of stuff.

But there’s credibility to the way architecture works and the way things are put together and the way things tell a story about whether this is real or not. Well, obviously it’s a fantasy, but if you can tell a real story about a detail that kind of lets the guests know that there’s somebody, the people who did this know, and they’re going to tell you the straight scoop and not just try to bluff you with a bunch of crud.

So that to me has always been something that I’ve been conscious of and I try to adhere to. And that’s no matter how little you have to spend on a detail, do the detail right, do it right. Even if there’s only one thing, like a bracket or something, do it right, because that little detail that you miss like that if you do it wrong or put it in a different time period, it could blow your whole story. And it’s not on a conscious level, but it’s on a subconscious level. For some of us, that was really important. And for me it was as well.

Dan Heaton: I think that’s important with Big Thunder, because like you said, there can be times where I’ll ride it and go, I never saw that figure ever that’s been there the whole time, or that little thing because it goes so fast. But like you said, if you’re in front, sometimes you spend more time just kind of going over the hill and you see things, but it’s the details that keep you coming back and riding it over and over. I think that’s really important. Well, kind of last summary for that is you mentioned your love of trains, and did you enjoy getting a chance to work on a railroad attraction even if you had to ride it 10,000 times given your enjoyment of trains?

Ray Spencer: Absolutely. Yeah. No, absolutely. I mean, always, always. Yeah.

Dan Heaton: Well, excellent. Well, one last question here. I asked this to a lot of people that worked at Imagineering or have had success in the industry, and I know there’s a lot of people that are aspiring to be designers or work on films or work in Imagineering. There’s so many different ways you can go now. Just from your experience, I’d love to know a little bit of what you might give someone advice on, not as much how to get into the industry, more like how to become really skilled at some particular part of it.

Ray Spencer: Yeah, that’s a good question. And I think that comes from understanding that for a lot of people, you really have to develop a skill. You have to develop that skill. And for me, it was thousands of hours of drawing and doodling and monkeying around with stuff. Knowing that a failure is not a bad thing. It’s a good thing you’re going to get to the next opportunity.

One thing that does not work for people ultimately is, and I see this often, and I know for me, just to back up a second, I mean, I grew up in the analytic log age where you draw with a pencil and you paint with paints and you do that stuff and making the transition to digital, it wasn’t hard, but it wasn’t easy. And for some it never happens. But all the stuff I’ve done for years now is digital.

I don’t think I would be as successful had I not put in the hours that I did with traditional methods. And because I had to understand relationships of color, I had to understand textures, I had to understand a lot of stuff that there’s really, I don’t know of any shortcut for. So I would say I also have worked with people that, and even when I taught at Art Center, it’s like, well, what do I need to know this stuff for? I’m going to be an art director. You don’t go from A to Z in just a vertical line and know everything.

You don’t; you have to learn something. Have to learn your craft. You have to study and align yourself with people and places that are very inspiring and understand why and really kind of work the craft. I don’t think there’s a shortcut for that, and if you find yourself taking those shortcuts, then you have to ask yourself, well, what am I in here for? Is it because I want a title? Is it because I want some kind of award or prestige or something that comes with that without doing the work? Because if you don’t do it, it’s going to be transparent and it ultimately lead to your demise or dismissal.

Dan Heaton: Well, on that happy note…

Ray Spencer: I don’t know. I mean, I don’t know what to say.

Dan Heaton: No, I think that’s great advice. All seriousness. I think everything you just said, putting in the work and really learning how spacing and how things work together and flow is very good, practical advice, seriously for anyone.

Ray Spencer: There’s tons of people that are really just passionate and selfless and motivated, and there’s a lot of people that are very, very good at what they do, and also just very selfless, and I found so many of them at WDI and other places, and those to me are the heroes and everybody can be a hero. It’s just if you’re not that, then you’re going to find that there’s others around that are that.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Well, I know there’s a lot more we could cover. I would love to, at some point in the future, do another podcast if you’re interested, because I know that Hatbox Ghost, the Matterhorn, so many other changes you worked on Trader Sam’s. There’s too much for us to cover now, but it’s been awesome to talk with you and thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Ray Spencer: It’s my pleasure, Dan. Thank you so much for having me.

Leave a Reply