Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

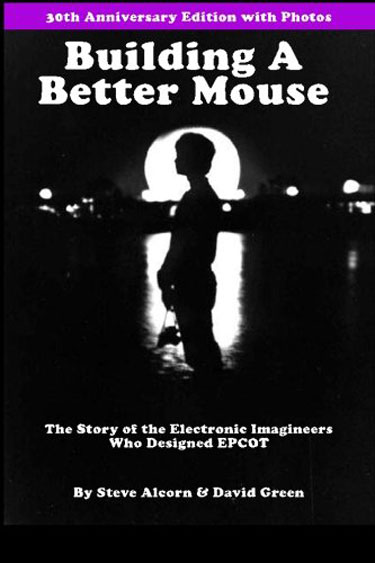

One of my favorite books about Walt Disney World is Building a Better Mouse: The Story of the Electronic Imagineers Who Designed Epcot. David Green and Steve Alcorn co-wrote the book, which gives us an insiders’ look at the atmosphere during EPCOT Center’s construction. What I love about the book is the way that it documents the daily work of engineers building a highly ambitious project. The chaotic pace led to a remarkable theme park. This isn’t your typical Disney history book.

My guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast is David Green, who talks about working on the construction of EPCOT Center in 1982. David worked at WED Enterprises for three years, including his time during the final months of construction. His stories about that time in Walt Disney World’s expansion that he recalls on the podcast are so cool to hear because they aren’t the normal Disney history. The young team of artists and engineers worked crazy hours to bring the incredible park to life.

David talks about his other roles at Disney in the 1990s when the company was growing quickly under Michael Eisner. Projects had great potential but then were stopped despite their success. We discuss David’s interest in themed entertainment and what interested him about documenting his experiences in the book. He also worked on the PeopleMover project at the Houston Airport, Tokyo Disneyland, and more during his career.

Show Notes: David Green

Learn more about David Green’s work at Visual Terrain on their official website at visualterrain.net.

Follow David Green on Twitter at @Visual Terrain.

Purchase a copy of Building a Better Mouse on the Paperback or Kindle versions through Amazon.

Listen to Dan Heaton’s appearance on the Book of the Mouse Club podcast and follow them on Twitter at @BookOftheMouse.

Support the podcast with a one-time donation and buy me a Dole Whip!

Transcript

David Green: We were working under CommuniCore at the park and we’d walk through the park every day and we’d go and check out as the shows were being brought up and we’d do the testing and we’d run through the tests until three in the morning and it was really this great thing. Then on opening day, you look out the gate and there’s 30,000 people waiting to get in and you realize it’s not my park anymore.

Dan Heaton: That was author and former Imagineer David Green, and you’re listening to The Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on episode 109 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. As always, I am your host, Dan Heaton. I hope you had a good 4th of July weekend and you’re hanging in there trying to keep moving forward. Stay positive as much as we can because it is a challenging time and it is showing no signs of letting up, but I’m just trying to take it one day at a time and I hope you are too. I’m really excited about today’s show.

My guest is David Green. He’s the co-author of the book, Building a Better Mouse with Steve Alcorn. In the book, David and Steve talk about what it was like to be an engineer working on the construction of Epcot Center during the months leading up to opening. I’ve wanted to talk to David for a while, and so it was really cool to finally get to hear his story about how he ultimately joined WED in 1980, what it was like to work on Epcot Center at such a busy, crazy time for the company, and making this really cool park from the engineering side, which I think is really interesting to hear about the other end of it.

David also has worked at Disney in other roles on software, and he talks about that another 11 years during the 1990s. So I haven’t really talked to too many people that have that perspective of working beyond Imagineering in different roles at the company, especially during a time under Michael Eisner’s leadership when the company was really expanding. We also talk about what David is currently doing at his company, Visual Terrain. He’s had quite a career much beyond the three plus years that he worked at Disney from 1980 to 1983. So it’s fun to talk about both what he did with Disney and then some other things too and what interests him in general about theme parks and the theme entertainment industry.

It was really cool and I think you’re going to enjoy it, especially if you’re interested in the background of Epcot Center living at Fort Wilderness and what that group kind of did at the time. I’m super excited for you to hear this show with David. He was a lot of fun to talk with and had a lot of great stories. So let’s dive right into it. Here is David Green.

(music)

Dan Heaton: I’d love to know kind of how you got started when you joined WED in 1980. How did that happen? How did you join working there?

David Green: Well, it’s funny. I was working at a small company in North Hollywood that created air conditioning test equipment of all things, and they got bought out by a bigger company in Chicago and moved the entire operation back to Chicago and laid us all off. While I was looking for another job, my dad, who was an ardent Disney fan, noticed an ad, a classified ad in the LA Times, and he gave it, cut it out and gave it to me and said, why don’t you apply for this job? It was a job at Walt Disney Imagineering, which at the time was called WED Enterprises. And I put together my resume.

I was 19 years old and I put together a resume that was four pages long and sent it into them. I really was totally unprofessional; I had no idea that four pages is way too long for a 19 year old, but I thought I wanted to show them everything I can do and I sent it in to them and didn’t hear back from them. And in the meantime, I got hired at another company and went to work building communications equipment. After I’d worked there for about six months, I got a call from WED and they asked me to interview. So I interviewed with them and they offered me a job and I actually turned it down because it wasn’t enough money.

I think they offered me $5.50 an hour and I held out for $6 an hour because I was 19 years old and I didn’t want to drive to Glendale without the extra 50 cents an hour to cover my gas for the week. And surprisingly after they hung up the phone three days later, they called me back and they met my offer, met my request, and so I started working there and I really had no idea what I was going to do. I knew I was working in the engineering department; I knew it was on some new project that I didn’t really know what it was and went and reported there on my first day.

My first day they walked me around, they introduced me to a bunch of people and they introduced me to a guy named Mark Gardner who was an engineer specializing in software and programming. He said, Hey, since you’re the first one here and this just came in today, I’m going to give it to you and you’re going to learn this and teach everyone else how to use it. It was the first desktop computer as far as I know in the department; it was an intel development system with two eight inch floppy disks on the top of it. It was a massive system, like a small console TV. They gave me a cubicle, they put it on my desk, and they told me to learn this system. That’s what I did for the first few months there.

Dan Heaton: That’s interesting. No pressure. So you were that young and you did that. So I’m curious too, I mean you mentioned about your dad, but did you, well, did it mean much for you to work for Disney? I mean, it sounds like given that you turned it down and everything that maybe it wasn’t that big a deal, but did you realize what you were getting into at all when you started there?

David Green: No idea. I mean, our family went to Disneyland every year, usually just once a year. That was pretty common back then. It was kind of seen as something that you wouldn’t go to more than once a year. It was kind of expensive and kind of a big deal to drive out to Anaheim from the Valley every day for a day. So we went once a year, maybe in a special year we’d go twice. And I liked it.

I loved Disneyland, I loved everything about it, but I was thinking more in terms of being in aerospace. I think I had started in college in engineering and realized after a semester or two I really didn’t like it. So I had switched to radio, television, film. This was 1980, and Disney at the time had Disneyland, which I’d been to, and they had Disney World, which I’d never been to. So I really didn’t appreciate what I was getting into at all until after I was there for a while.

Dan Heaton: So you mentioned that you worked on the desktop computer. So what did your role end up being? I know it’s an engineering aid, but you could talk a little bit about what you did there as you went along at Disney.

David Green: Well, actually my initial title when they hired me was a wire lister. And a wire lister is a person who takes engineering drawings and if an engineering drawing shows, it’s like a blueprint, but it shows a symbol of a cabinet on one side and a cabinet on the other side, and the cabinets have to be connected and they show the connectors and you have to make a list of all of the wires from connector a pin one to connector b pin one on the other cabinet, and then the technicians in the field are going to wire these things up, but they need to know how they get wired up.

So my initial job was to create these schedules of wireless from the engineering drawings, but they weren’t quite ready for me to do that yet. So they threw me over to Mark Gardner and had me start working on learning the computer.

His project that he was working on currently was the Houston Wedway PeopleMover. So that was the first thing that I got assigned to and I did the wireless for the Houston Wedway PeopleMover for probably six months or a year after I started. I don’t really remember the timeline now. That I was really excited about because it was transportation engineering at the time, Disney thought because of the Monorail and the PeopleMover that one way for them to expand as business was to create transportation systems for municipalities.

They were really looking at it seriously and they had a great engineer, a guy named David Turner who still friendly with to this day, and a guy named Bill Wolf who’s another great engineer. They were working on the design of the system with other companies that were outside of Disney and consulting firms and they created this Houston Wedway PeopleMover, and it was one of the few projects at the time that Disney did. It was finished on time and under budget and it worked almost perfectly from day one.

It had like 99.9% uptime they called it, which is the time that it’s operational and not having problems or shutting down systems or cars because there’s issues. The thing was really well designed and it ran really well and Disney finished it and then said, no, we don’t want to be in that business, and they never did. another thing.

Dan Heaton: It’s crazy, it’s still because I grew up in the, I was a kid in the eighties and love things like the PeopleMover and the Monorail and all that. So now that I learned more as an adult about that, and as a kid I thought there’s going to be PeopleMovers everywhere and it’s going to be a thing and it’s still, I know a lot of it is Michael Eisner and what he wanted to do, but it’s still kind of, oh, it kind of bugs me.

I think what could they have done or what could the technology have done? It’s really cool you got to work on it because that Houston PeopleMover is still kind of put out there as the one example. They never got further. So I think it’s really cool, you got to work on it, it’s just too bad it didn’t go further.

David Green: It was very frustrating because it was a success in every way. It did what they needed it to do. It did it well, it did it efficiently, and had really good operational uptime and they still said, nah, not right for us. I want you to keep that in mind because it foreshadows other things that happened to me later at Disney. It’s kind of a recurring theme.

Dan Heaton: Oh yeah, I’m sure just with what I know about how things went, especially we’ll get to it, but after Epcot and everything, it’s a tumultuous time I will say. But I’d love to hear about, I know you worked on the construction of Epcot in some way and I’d love to know just at first when you got moved over to that and then what was the atmosphere like while Epcot Center was kind of coming together?

David Green: Another case of my sort of ignorance as a young person when they first asked me in 1981 or ‘82 if I wanted to go to Epcot because we were all working in Glendale and people were getting sent over there little by little, I think Linda Alcorn may have been the first one to go. Then other engineers followed quickly thereafter and they said, David, do you want to go to Florida? I said, no thanks; I had no interest in going.

I was actually still in college, of course, I was only at that point 21 or something and I didn’t want to mess up my schooling. They asked me to go and I said no, and I was living with my girlfriend in Glendale and I just didn’t want to mess things up. Then after everybody started going and we started seeing pictures coming back and people started coming back with stories of what it was like to be in the field, I changed my mind and I was really regretting saying no.

Things got so busy; they came back to me again in May of 1982 and they said, are you sure you don’t want to go? And at that point I said, okay, I’ll go. I went for what was supposed to be a three-month trip and it ended up being I think nine months that took me all the way through opening day. And it was the most incredible experience of my life to that time.

When we arrived, it was all mud. There was very little poured concrete. You are walking through the mud every day. The pavilions were up, some still had open frames, they’re installing stuff, there’s cranes everywhere, there’s earth movers everywhere. The first day I got on site, they said to me, go into the field, find the monitor cabinet, which was a cabinet of equipment that monitored the attraction and sent the data back to the CommuniCore and they said, find the monitor cabinet for each attraction and make sure that the wireless and some other programming documentation is in the little pouch inside the door of the monitor cabinet.

In a way it was kind of a hazing, but it was really actually a trial by fire because it was really a great way to get to know where every pavilion on the site was, where every monitor cabinet was because I was going to be working on that for the next nine months. So you kind of go through the site and I thought, oh, this is quick. I’ll go through each pavilion and find the monitor cabinet and check the documentation and then be back at the office in an hour or two. I was probably out until late at night just trying to find the monitor cabinets.

The doors were locked, the buildings were closed. There was no way to get in. There were always issues. You get there and you find the monitored cabinet, there’d be no documentation in it at all or there’d be a wrong documentation. So it was a really great introduction that first day just to go through the entire park.

Dan Heaton: That pretty much shows to me just how challenging it was given that everything was still kind of like you mentioned disarray with things being locked and open and everything. And also just how big Epcot is. I know just walking around as a guest, it’s a huge space and I’m not even talking about back of house, I’m just talking about the park itself. So as it got closer to during your time, it was very soon to when it opened, how chaotic was that when things were still being put in and you were just kind of running all around? How crazy was that during that time?

David Green: I probably worked the least of anybody on my team and I worked a minimum of 80 hours a week. Other people were working a hundred hours, people who were working on American Adventure, there’s 168 hours in the average work week, and they were working 140 hours. It was just people were getting three and four hours of sleep a night if they were lucky. I think we described it in the book where Glenn actually took a sleeping bag into American Adventure and was sleeping in the attraction so we didn’t have to waste time going home and showering and eating and those pesky things. So it was very intense and we all knew we were working hard for the most part.

We loved it. If you were there and you were single, you probably had no issues at all. It was really tough on the married people because even if you’re working with your spouse at Epcot, it’s just really hard either being apart that much or being on separate hours scheduled because very few people were on the same schedule. So it was just really hard on the couples. There were a lot of divorces after Epcot and a lot of people who went to Epcot single came back married. So it was really a crucible for relationships and very tough on a lot of people.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I can imagine. I mean working that much and especially the 140 hours, that doesn’t sound very healthy either for anyone. But I guess that’s what it had to be done because at least, and I don’t know how much your work went with this, but there was so much new technology kind of being tried and being put into it. I mean, how much did you see of that? I mean, was it a challenge for everyone to deal with all the technology that was being put into that?

David Green: Yeah, I mean there were a lot of things that were new to us and new to their uses. There were things that were not that new technology, but they’d never been used in this way before. And so the engineers there were though because they were so young and so passionate, they didn’t look at it as a problem. They looked at it as a challenge. They looked at it as something to overcome and that’s why they worked 140 hours because they would just hunker down with a piece of equipment until they mastered it.

On my personal side, the early on when I was there is when I transitioned from being a wireless to being an engineering aide, and they just had me, basically just the engineers in anything they needed. I reported to all the engineers that were there and just when I was done with the task for one, I’d go to the next one and say, what do you need?

And so early on, it was a trailer at the edge of the property called the retreat, and it was just a horrible, a double wide trailer with a dozen engineers crammed into it. I went over there and said, what do you guys need help with? And again, it was Mark Gardner said to me, do you know assembly language? I said, no. And he goes, well, you got to learn it. He gave me a stack of code, a printout about an inch thick and said, I wrote this program.

There’s a couple of bugs in it and I can’t find them, so just go through this and learn the assembly language and figure out where the bugs are. I spent a week just going over the code and with a book on assembly language next to me so I can understand what he was doing. And at the end of the week, I found three bugs and I turned it back to him and he says, great. Now here’s another stack of code. So that’s how I learned to code assembly language. It was just everything was done sort of by crucible and everything was feet to the fire and everybody was in it together, and it was a really incredibly collaborative and intense environment.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it sounds that way. I know when you were on site, I believe you were living in trailers in Fort Wilderness, and what was that like?

David Green: It was great for me. It was really my first extended time outside of California, and like I said earlier, I didn’t really want to go to Florida in the beginning and after a few weeks in Fort Wilderness, I loved it. I loved Florida, I loved the humidity, I loved the afternoon rainstorms, I liked living in, it was the end of the wilderness.

There were bugs and critters everywhere, and you’d come home at night and there’d be palmetto bugs on the outside of your trailer that were two inches long, and it was just kind of an immersion. It was camping out with kind of, I wouldn’t say luxury, but with comfort at least was camping out with comfort in a really beautiful place. So you didn’t mind working those hours. You went home and you were really kind of surrounded by beauty in a way that Disney does so well.

Dan Heaton: I find it fascinating just the whole thing because now we look at it and everything’s so put together, but it was just dirt everywhere and all that being on site, it was how close to the opening? Were things still kind of in flux or I guess still not ready?

David Green: Some pavilions were done with time to spare and others were still being tested on opening day and there were a few openings. There was an opening, I think Labor Day, there was a soft opening. There was a soft opening, I think September 23rd, which was for crew, which was all the construction crew and employees were working there. And there was the official grand opening on October 1st for the public. Even that was kind of a soft opening.

There weren’t massive crowds in the beginning and things were still being ironed out. I think American Adventure, I’m going to test my memory here, American Adventure, Spaceship Earth, and I think Imagination opened previous for executives and then shut down immediately and didn’t reopen again for a few months. I think everything else stayed open the way it was supposed to. And one thing that was really fortunate was that the attractions like China, Canada, and France had movies and once they got those running, they were really stable.

So those were good ways to keep crowd capacity up, keep things going, get people in, and you didn’t have to worry about something breaking like you did in Spaceship Earth or American Adventure, which were extremely technologically complex attractions. And even probably for a few years after they opened, were still subject to glitches and pauses in the show where they’d have to say, okay, everybody, we’re going to reset, start it over, not let anybody in, send everybody out, and then close it down for a few hours while they figured out what the problem was. There were still issues like that after opening American Adventure.

Dan Heaton: I’m still kind of boggles my mind the amount of the technology for that show. I’ve never gotten in there and seen behind the scenes, but it’s one of the crazier things that I can still imagine. And the show is almost 40 years old. It’s crazy to me. And Spaceship Earth the same way at the time, just really high tech. So I’d love just to kind of sum it up in terms of when you worked on Epcot, you look back at it now, beyond kind of what we’ve discussed, what stands out to you just about your work? What are other maybe favorite memories or something that jumps out at you?

David Green: Really the camaraderie that we had all the way through really. It was really just a sense of some people have compared it to sort of being in the military, but I think that’s probably not quite an apt comparison, but it’s similar in the way that you’re going, undergoing a very intense experience and everybody’s in it together and everybody, the egos get shaken out pretty quickly.

There were people who were sent back to California or people who were let go and everybody else there is willing to work together and you just work long hard hours together and you try to help each other out every way you can. And then when you’re not working together, you’re playing together because basically whenever we weren’t working together, we were out eating dinner together, we were out getting drinks together, we were going to the beach on weekends, you think like, oh, after spending all time with people, you’d be sick of ’em, but it was the opposite.

We just really hung out together and you have bonds with those people where the core team that I was working with then I still see personally now and they’re still friends and we’re Facebook friends and we get together when we can and at least once or twice a year and share memories. And it’s just a really great bond to have with working people that it’s not that common. I didn’t know at the time, it wasn’t that common. I thought everybody had jobs where you worked intensely like that and had these lifelong friends.

Dan Heaton: I think that part of it too might be that, correct me if I’m wrong, but everyone was really young too. That’s what amazes me when I look back at Epcot or even at some other parks that were built, is how many people were in there, like you mentioned your age were in their twenties and were doing just so many complicated things and working so hard. I guess maybe that’s part of how you could do it was being so young.

David Green: Steve likes to say we didn’t know it was impossible, so we did it. A lot of people were straight out of college, they just got their degree and started at Disney. They got the degree in May or June, and they started at Disney in July. That was really common. Management was more senior, definitely management was, and they were still young by today’s standards. They were in their thirties, but they’d had a couple jobs. A few people came from aerospace and they knew how to manage a big project, and they used to talk about the fact that they left aerospace because they were tired of building bullets and bombs, they called it, and they wanted to build something that made people happy. So they came to Disney and they managed projects and they managed them really well. They were super organized, efficient.

If you think of aerospace and you think of the good side of aerospace and the Apollo program and things like that, there were those sort of people making this happen, and they kind of figured out early on, get these young people in and unleash them and let them go at it. And I can’t imagine a 40-year-old being willing to go down there and work 140 hours the way a 24-year-old would.

Dan Heaton: Totally. And actually the Apollo program is a really good comparison because even I read up on that and the same sort of thing where you look at a lot of the people that were working in Mission Control and everywhere, and you’re like, they were so young, so many were under 30 and had so much responsibility. So that’s a good connection. But I’d love to hear too, I know you worked on a few other projects when you were still at Disney, including the Fantasyland rehab at Disneyland. I’m curious what you did for that one.

David Green: On that one, I was back to more just wireless listing. It was not as exciting for me personally. I was only on site. I wasn’t on the site where the work was being done; I was at Disneyland for a couple of weeks, interestingly, working in an office that was underneath Country Bear Jamboree. It was interesting because every afternoon in the mornings it was quiet and sometimes you could hear the music upstairs, and then the afternoon after lunch, the crowds came in and they were rowdier and they were just more awake and you’d be working and suddenly the ceiling would be vibrating because people would be stomping their feet. It was a really interesting environment.

I loved the project when it was open. I was there for the opening day and it was wonderful, but there was not much of excitement as far as my work on that. The one funny story I can tell you is there was an engineering office underneath Country Bear Jamboree I was lent to for that project. And my last day there, one of the guys who was there was actually leaving to go on elsewhere in the company or to another company. It was his last day, and he’d worked in that room for five years with the music and the stomping. So they gave him the soundtrack album of Country Bear Jamboree because they said he probably couldn’t get any work done without it.

Dan Heaton: Oh my gosh, five. That sounds, I’m sure you’d have to blot it out at some point, but that’s crazy.

David Green: Yeah, how many shows he must have listened to. And like I said, it was very faint. It was well insulated floor, but you’d hear it in the morning, you’d hear the bear necessities being sung.

Dan Heaton: Oh, yeah, especially the finale when they want everybody to clap and stop and it’s like, oh, oh boy. That would be a lot. So I know you also worked some on Tokyo Disneyland, which opened just a bit after Epcot, so I’m curious what you did there too.

David Green: Yeah, same thing, but that was more back to the wireless and just preparing the wireless. I didn’t get to go to Tokyo, but I prepared the wireless for the engineers who did, guys like Ira Frank and John Noonan who had really long careers with Imagineering and I think probably 30 years plus. It was wonderful to see, and I have wanted to go there ever since and actually never been to Tokyo Disneyland. It’s on my bucket list for sure.

Dan Heaton: Same here. I haven’t been there too. And someday, someday I’ll be able to make the trip, but from what I’ve heard, it’s an amazing resort. You mentioned the book Building a Better Mouse, which you wrote with Steve about true experiences at Epcot Center, and I really liked the book, but I like the way it kind of what you described, it really brings you into what it was day to day to be there. So I’m curious how you got into writing that book with Steve and how that came about.

David Green: At the time, I mentioned I had started off as an engineering major in college, and I switched to radio, television, film, and then I switched again because what happened when I started working at Disney is I found out I could only take night courses and I couldn’t take radio, television, and film at night. So I switched to journalism and really discovered I loved writing.

So the last few months I was at Disney, everyone was being laid off. It was during the post Epcot and post TDL layoffs. They told me I could keep my job if I would document all the systems for them. So I got to work for an extra six months basically writing technical documentation for all of the systems I’d worked on so they could keep them and maintain them after I left and after all the engineers were laid off, that’s sort of got me more into writing and I thought I should really write about my experience here because it was such a phenomenal experience.

I was really influenced by Hunter S. Thompson, whom I loved on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail and his books. And I loved Tom Wolfe who wrote The Right Stuff, and I believe the movie of The Right Stuff had come out by that point, and I really wanted to write the Epcot experience with as much sort of gonzo feeling as I could because it was so intense and I wanted to capture that.

So I started writing this book at the same time, I didn’t know it, Steve Alcorn was starting to write a book, but from a different perspective, he wanted to sort of cover it from the perspective of the engineering achievement that Epcot was. We started working together again after we both left Disney and we were talking one day at lunch and we realized we were both writing a book and he said, we should write it together.

So we started collaborating on it, and after sending a few drafts back and forth, our styles were just so different. So we started kind of collaborating less and less and less. And then Lynn Electronics, the company we’re working for went out of business and I went back to college to finish my degree finally, and Steve went on to work at another company called Cambrian Systems and the book, we just sat at that point, nothing happened with it.

And then 20 years later, I got a package in the mail, and it was the manuscript of the book that Steve had finished. He had taken everything I’d written and everything he had written as well as all of Glenn Burkett’s notesl. Glenn Burkett is sort of the uncredited third author of the book. He really deserves to be credited on the cover because during the whole time of Epcot, he knew what he was getting into.

He knew how great it was; he kept almost a nonstop verbal record with a little mini pocket tape recorder of everything that was happening just to have something like that, a document in real time of, I just had a meeting with so-and-so and here’s what we discussed, or I just had three hydraulics just blew up in the fourth carriage on American Adventure.

I mean, for him to do all that in real time, it was great information and allowed Steve to go back and mine his own memories for what had happened and talk to people and piece things together. So Steve finished the book and sent it to me as sort of a galley proof, and I read it and I proofread it and I marked things up and I made changes and I added my own touch to a few things and I sent it back to him and he published it. I was really lucky that he did that because otherwise the book would not exist.

Dan Heaton: That always interested me about the book because it’s written, it came out, you wrote it in 1983, and then it came out so much later, and I was always thinking, well, why did it take so long? So that makes a lot of sense. But I love the idea too, the way the book was written. It wasn’t written like, I did this, I did this. It was written, your name’s in there, David did this, or Linda Alcorn or Glenn or whatever.

And so when you mentioned those other authors, I’m like, oh yeah, I can see it because, and I know you didn’t write all of it, but a lot of the part you wrote, it’s very, like you said, it’s kind of like you’re there, but you don’t always know. It’s not straight narrative. We arrive, we did this, we did this. It’s very kind of all over the map.

But I like that because I feel like it gives us a better idea of what it was like. And you mentioned Glenn, there are I think one chapter where it has timestamps and it goes through a day or a few days of what kind of he’s doing. So it’s fun. I like the way that it, there really isn’t another book that gives you that experience, especially of that park. Most of the books are like the history, they talk about the attractions or they focus on that. They don’t really focus on it from your perspective. So I think it’s really cool.

David Green: Yeah, I was really lucky, and I give Steve all the credit for that because when we were working early on, I was writing the book entirely from my perspective, and he was writing the book pretty much entirely from his perspective. Then we had the tape recordings from Glenn and Steve said, we were talking like, how are we going to make this blend? And Steve said, let’s composite it. It’s either third person or it’s I, and whenever it says I, it’s really not any of us or it’s all of us. It was a really good conceit literary from a literary standpoint to bring it together and give it that one voice, but multiple perspectives.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, definitely for someone like me that obviously only knows the park as a guest, to be able to kind of for a few minutes step into your shoes or step into Steve’s shoes or everything, it’s really fun. So I like that approach. And you mentioned too your interest in Journalism and English, and I know you have degrees in those subjects like an MA in English. So what really got you excited about being a writer or about working in that field?

David Green: Well, it was kind of a bizarre path because as I said, I started off as a television film major and then switched to journalism pretty much only because I couldn’t get the classes that I wanted, and I knew I wanted to work in some sort of creative field. So I wasn’t a news journalist, I was more of an entertainment journalist. I was the entertainment editor on the university newspaper at Cal State Northridge, and I was the features editor one semester.

I’ve always loved music, I’ve always loved the arts, and I wanted to report on it. I wanted to write about it and I wanted to discover people, and that’s kind of what got me into it. Then once I got my journalism degree, I finished that and realized that I really enjoyed the English classes I’d taken and I wanted to be a better writer, and so I went back and got a degree in English after that.

Dan Heaton: Well, you could tell just with the book and how it’s written that there’s some writing style there for sure. Well, I don’t want to go too far without, I should ask you then. You referenced it already that you left WED and we’re laid off and such. So I mean, I don’t know how much you want to talk about that, but I’d love to know at least a little bit about that experience for you.

David Green: Yeah, there’s a really interesting story that goes with that because they were having layoffs and they were laying off. It was not all at once. It was many people a week for many weeks, and it had been dragging on, and it was almost always on a Friday, or sorry on a Thursday and they’d call it black Thursday. They’d start calling people into the management office up front, and then people would come back with their boxes and load up their boxes and then they’d leave.

It was very stressful and nobody knew when they were going to get the ax. I realized that it was getting to the point where our little team, the wireless and engineering aids was about to get the ax, and it was like none of us had been touched yet. We’re finishing up our projects, one of us is going to go, and I had recruited two of my close friends to come and work with that group who were both engineering majors and really wanted to stay with Imagineering.

And on the other hand, at that point I’d switched to journalism, so I knew I wasn’t going to stay with engineering. So on Wednesday, I walked into my boss’s office and I said, look, I know we’re probably going to have layoffs soon, and I want to let you know if you’re going to lay off any of the three of us on this team that I volunteer to go.

He was really surprised, and he asked me why, and I explained it to him and he goes, okay, that’s a really fair reason and it’s a really nice thing for you to do, and I’ll keep that in mind. And the next day on Thursday, they laid off a bunch of people and they laid off nobody from my team. I was really amazed and I thought, well, I guess we dodged a bullet there. Maybe I was premature and we’re not going to get laid off. And then the next day they called me in and I got laid off.

Dan Heaton: Oh boy.

David Green: So I think what happened is that they were probably planning to lay off one of the other guys, and my little notice was not early enough for them to fix it, so they had to delay it a day to get my paperwork together and laid me off the following day. And the layoff was so efficient and kind in a way they set you up with a counselor and somebody who helps you through the process.

They had a company that were placement advisors, and they had a big office fairly near to the campus, and you’d go in there and you could make calls and set up interviews, and they had multiple newspapers so you could go through classified ads. There was no Internet at that point to go through and find a job. So it was a really nice program that kind of helped you launch into the next job.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s good, at least to hear not the layoff part, but that’s good to hear that they were doing that at least because yeah, I mean, I’ve heard about it from others and then also I know they talked about it on the Imagineering Story series that came out recently, and it’s sad that that had to happen because like you mentioned, there was this great environment and there was so much going on, but projects like Epcot don’t come around every few months or something.

It’s such a big project, but it’s really too bad. But I do think, I mean, it’s interesting that after a while you ended up going back to Disney, not at WED, but in variety of other roles during the 1990s. So I’m curious for you, I mean, what was that like to go back and then maybe about some of the roles you did?

David Green: I had a friend who worked for, we worked at the same company, a company called CA in Burbank that was a division of Lockheed that created CAD cam software similar to AutoCAD. And one of my friends left and went to Disney and got a job in it, and it was sort of a growing field at the time, and he said, you’ve got to come over here. It’s great.

I’ve got a great boss, you’ll really like it. So I went and interviewed and got hired and worked in the studio IT department, and my boss was a guy named Art Holland, and I’m still friends with him today, a really good guy and was a sort of ragtag bunch of eight guys who were all IT support people, and I was a Mac guy, and so I got assigned to feature animation. They were mostly Macs.

The ratio of people you supported to technicians was kind of crazy. I had the fewest users, I had 150 users that I supported, and other guys had as many as 400, and we basically go out and help people use their computers at work, and things were new back then. E-mail was new. Laser jet printers were relatively new. This was 1986, I believe. No, sorry, 1990. This was 1990.

So yeah, so it was a very strange time, a great time to be working with computers back then. After I worked at feature animation for about a year and a half, there was a project that came up called Fame, which was the feature animation management enhancement tool, which was something that used to do manually with old school hand-drawn animation is they would track where all the different cells were, where all the different seeds were, where all the different sequences of scenes were.

They tracked it on big spreadsheets basically, but they were all done by hand and they wanted to do this with a computer. The group that was doing it was also run by Art Holland, my boss, and there was a guy on the team who wasn’t performing well and they fired him and they asked me to come on and I said, but I don’t know the programming environment that you’re working in. He said, you can learn it. He said, you understand feature animation and it’s easier for somebody to understand feature animation, to understand programming than to teach a programmer to understand feature animation.

So sort of my first task at Disney is I was the one who came on and learned a programming language in order to help them put out this system. And I understand, I met with a friend who worked with feature animation, and this was in 19 91, 92, and I heard that the system was still in use there, which I can’t believe they must have updated it by now, but at least the system with the same name is in use there.

Dan Heaton: Wow. So yeah, I guess it’s like a through line based on, like you said, you taught yourself the programming with the book at Epcot, and now you have to do it again. I think somehow your bosses always can tell that you’re going to figure it out or something.

David Green: Yeah, maybe I am actually still surprised when it happens. Maybe I’m not self-aware enough. I don’t know. It’s funny that that’s happened a couple times.

Dan Heaton: So you worked at Disney generally through the nineties, right? To early two thousands I think for about 11 years. So I mean, just in general, looking back at that, what was the environment like? The company was growing so much at that time in the nineties. I’m curious for you just with your roles, what was that experience like?

David Green: So much was dependent upon which department you were in. I mentioned when I started, I was at it, and actually it was hellish. It was actually really brutal, not a really pleasant place to work. Basically, I was dealing with everybody from entry-level employees up to VPs at Disney, and you’re kind of the IT guy, so you get mistreated a lot, you get yelled at a lot for things that aren’t your fault. It was very stressful, long hours.

I remember on my 30th birthday thinking I had made a horrible mistake because I was working and it was a long day and I was having a really, really bad day, and I got called into the VP of Finance’s office. She was having problems printing a document, and because she was VP of Finance, she knew employee records and somehow she knew it was my birthday and she closed the door behind me and she goes, I just want you to let you know breathe, have a happy birthday.

It just made all the difference in the world. It’s like, oh, it’s somebody knows it’s my birthday. This is so nice. There’s no cake or anything like that. But it was just like, okay, it felt really good. It helped me get through the day. The job I had after that was working with a group called Disney TeleVentures, and that was a project that was basically television over the Internet before there was an Internet, and it was a partnership with Disney and five telephone companies to create this service so that people could watch TV and do things like order pizza.

If you see a Domino’s ad come up, you’d press a button on the remote and you’d order a pizza and order clothes. If you were watching a show and you love the clothes that the actor is wearing, maybe you’d do a search and you’d find out what they were wearing, you could buy those clothes.

It was a really ahead of its time concept. And we worked on it from 1995 to 2000, and then we rolled it out. It actually was tested in a few places through a company GTE, which I don’t even think they’re around anymore, a telephone company. It was very successful and people loved it. And just like the Houston Wedway PeopleMover just before it was about to roll out, Disney said, yeah, we don’t really want to be in that business anymore. And they shut that project down.

Then literally the week I was about to be laid off, my boss called me into his office and he said, hey, we’re going to start a new division at the company, and we’re going to create basically a lift of what we’ve been working on for the last five years, and it’s going to be part of movies.com, and it was basically Netflix in 2001, and we worked on that for a year, and it was coming along really well.

At the end of the year, the analysts at the company looked at it and said, yeah, there’s not enough broadband penetration for this to be profitable and they kill the project. Here we are now almost 20 years later, Disney Plus just coming out now, which is basically the same concept at least of what we had worked on back then.

Dan Heaton: Knowing how internet was at that time, I can understand it, but it’s still too bad because yeah, they kind of were a bit behind the curve now. Disney Plus is great, but that it took that long. It’s interesting that you had that experience.

David Green: Yeah, I mean, I think if they had just rolled it out slowly and within three years there were other companies doing similar things, and I think Disney would’ve owned that space if they had stuck with that project, they really would’ve been so far ahead of the game with both of the projects, with both of the Disney Televentures and the movies.com. It breaks my heart still to this day to spend basically six years of my life working on projects that never got realized.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I can imagine. Because it’s one of those things where you’re kind of doing this new technology, it has so much promise and it’s exciting, and then just bam, done. It seems a little more foresight might’ve led to something different on the company’s part, for sure.

David Green: Yeah, I think so. And to be honest, nobody knew back then how big the Internet was going to be. They knew it was going to be big, but just not how big.

Dan Heaton: Oh, totally. Yeah. I don’t mean to be too critical. I think that so many companies now look back and just go, what were we doing? So it’s not a rare story, I’m sure. But I’d love to ask you too, I know you have some other interests that I find interesting. One of them is you’re a photographer and you’ve done a lot of in fashion and architecture and music, so I’d love to know a little bit about that. What do you do there?

David Green: Yeah, photography is something I’ve done since I was a little kid. My dad gave me a camera when I was nine, and I was immediately hooked, and I had a dark room, a film dark room in my bedroom closet when I was in my teens. So I’ve always done photography. In about 2005 when digital photography started getting real, I bought a Canon Digital camera and really just gotten totally sucked into that.

I did it professionally for a few years as sort of a side business to my main business of doing user interface design, but now I just do it as a hobby and as an art form sort of passion and release. I love photography, I love doing it as president of the Santa Clarita Valley Photographers Association for a couple of years and met a lot of great photographers and it’s just a great creative release for me.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I can imagine. Yeah. It fits with everything else I think that you’ve done with writing and so much more. And also, I’m a big fan of just the history of, I mentioned Apollo earlier, very interested in all that. I believe you wrote some software about the history of manned space flight and then some astronomy logs. So what excites you just to do that?

David Green: Being in Florida, when I was working at Epcot in 1983, we went and saw one of the early shuttle launches. It was just the most spectacular event that you can imagine. We were five miles away in a sort of a VIP viewing area. One of the guys’ fathers worked at Cape Canaveral or Cape Kennedy and got drive on passes for us. So we were one of the closest places you can be, and it’s five miles away. And when that thing takes off, you feel it. You feel the vibration all the way through your body, and it’s just such a visceral thing. Everybody, everybody there is staring at the sky in sheer awe and wonder and amazement. And before that even I was into the space program through Apollo and the moon landing. I was nine years old when we landed on the moon.

So I’ve always had a love for the space program. One of the guys I worked with at Epcot, a guy named Andrew Dobe, we got to be really close friends, and I decided at the time to create a HyperCard stack. HyperCard was a software development environment on the Mac, and I created a HyperCard stack for him for his birthday one year, and it was all in man space flight.

And I went into the warehouse where I was working, they had a shrink wrap machine, and I shrink wrapped the disc for him, and I made it look like it was professional, and I gave it to him and he thought it was a piece of professional software. I mean, he found out that I had created it for him. He said, you have to sell this. And so I found a company called Heiser Software that picked it up and distributed for me for many years until Apple depreciated HyperCard and stopped distributing it.

Dan Heaton: Wow, that’s interesting. That one that, yeah, I mean that you were able to present it in such a good way. And also two, it was really exciting for me just to see the recent space flight that finally there was manned space flight from Cape Canaveral again, and how cool that was, especially given what’s going on in the world, it was kind of a nice thing to see.

David Green: Yeah. Yeah, I loved watching that. It felt wonderful. A nice little bright spot in a very horrible year.

Dan Heaton: Oh, for sure. So I want to finish by asking about what you currently do. I know you’re currently the president and COO of Visual Terrain, so I’d love to know what Visual Terrain does and kind of what your role is.

David Green: Visual Terrain is a lighting design company that was founded by my wife Lisa Passamonte Green in 1990, sorry, 1995, just celebrating 25 years now. She’s a lighting designer who came up through theater at San Diego and worked at Imagineering. And strangely enough, we didn’t meet through Disney at all. We met through outside friends. Her college dorm roommate was friends with a guy I worked with, and that’s how we met.

She had the company called Passamonte Lighting Design, and she started that. And in 2001, Passamonte Lighting Design became Visual Terrain. And then in 2010, her other two partners at Visual Terrain left to pursue other things. She said to me, I need help running the company. You know how to run a company, so you’re coming on board. I didn’t have a lot of choice in the matter, but I was really happy to do it.

So since then I’ve been involved in the world of lighting design and perversely coming back into themed entertainment through sort of the side door because we do a lot of work for themed entertainment. We do a lot of work for Disney and Universal and along and other clients that are in the industry. And so even though I’m more day-to-day operations, I don’t do any of the lighting design and something I’m probably not going to learn at this stage of my life. But we have a team of 13 people and it’s something I didn’t even know existed really before I met Lisa, and now here I am running this company and really enjoying it.

Dan Heaton: So yeah. I’m curious too, just you mentioned getting back into themed entertainment for you personally. Are you interested in that? I mean, how interested are you and what kind of excites you about it?

David Green: Yeah, well, it’s funny with the history I have. One of the things about working at Disney that I’m sure you know about is they have for employees something called a Silver Pass. And the Silver Pass is basically a card you carry in your wallet that lets you into the park at no charge. You and three guests can enter the park anytime you want. Over the years, it’s gotten more and more restricted.

When I was younger, it was literally anytime you wanted you could get in. And now there’s blackout days and things like that. But I got really spoiled having a Silver Pass. And I would go to the park as often as in the summer, maybe every week I’d go during the holidays just to see the lights. I wouldn’t even go on any rides. I would just get into the park and go into Main Street and grab a bite to eat and look at people, watch and enjoy the light shows.

So I got really spoiled. And when I got laid off from Disney in 2001 and the first time I had to go back to the park and pay for it, it was really difficult to do. It was really difficult to be there with crowds, and it was really difficult to pay that much money. So I still love the parks, and we of course go there as often as we can because we need to keep up on what’s new in the parks for the sake of our business. But I don’t have the same joy that I had when it was just, I could go every week and just sit back and enjoy it and people watch and maybe after I’m retired that’ll come back. Then I will be able to go anytime I want.

Dan Heaton: Totally. Yeah, because in a sense, when you’re going and it’s like your money and it’s like maybe more, it’s like a vacation, whereas before, I almost feel like it’s the same if I was going to a park in my city or if going to a local attraction where yeah, you’re just like, there’s no pressure. You’ll be back next week. It’s almost like it’s not your home, but it’s like a secondary place that you just go to chill for a while.

David Green: And when you have that relationship with it, it’s really magical. For all the employees that are still able to do that, I’m sure they’ll say how wonderful it is just to be able to go to the park on a Tuesday afternoon when there’s nobody there in the middle of October or something and just chill and just enjoy the park for what it is.

You start noticing details; you start noticing how well everything is done and how clean everything is. You really get tuned to sort of the essential nature of the theme park. And it’s kind of special. You build up a special relationship. It’s sort of like when I was working at Epcot and we were working in the mudhole and everything was crazy and it was insane. And then things got cleaner and they poured the concrete and the buildings went dust free and everything was really nice.

We were working under CommuniCore at the park, and we’d walk through the park every day and we’d go and check out as the shows were being brought up, and we’d do the testing and we’d run through the tests till three in the morning and it was really this great thing. And then on opening day, you look out the gate and there’s 30,000 people waiting to get in and you realize it’s not my park anymore. And it’s sort of the same thing with the Silver Pass. When you don’t have that, it’s not your park anymore, and you’re sharing it with everybody else and it’s still great, but your relationship has changed.

Dan Heaton: Oh, totally. Yeah. I’ve never had that experience, but I can definitely understand just especially being involved at Epcot, but even just in general. So one other thing I wanted to ask you about is, of course, you are also the president of Monteverde Creative, which is the design consulting company that you started in 2001. So I’m curious about that and how much you’re doing on that these days.

David Green: I’ll be honest, I’m not doing much on that. That company was started when I left Disney the second time, I was looking for a job and my wife said to me, why are you looking for a job? You can never work for anybody again. Why don’t you just start your own company? And I said, yeah, I don’t know if I want to do that. She said, you’ve been watching me do it for several years, you can do it. And so I was kind of thinking, yeah, maybe I will.

And literally the next day, a friend of mine called and offered me a consulting gig, and I thought, okay, I guess the universe just sent me a big clear message on what I’m doing next. So I started the company and for basically from 2001 until 2011 when I officially joined Visual Terrain, I did UI consulting for primarily for large entertainment companies like Disney and DirecTV. And it was a great run once I started Visual Terrain, and I still did it for a while, but for the last few years, I really haven’t done any of that. I keep it open in case something happens,

Dan Heaton: Right? Just in case you never know.

David Green: My whole life has been a series of strange coincidences and odd phone calls when I least expected it. So it’s like, yeah, I’ll just keep this here. You just never know when something’s going to happen.

Dan Heaton: Oh, for sure. And I think that’s a through line throughout your career. Well, David, this has been amazing. I’ve really enjoyed learning more about your story and so many different things that you’ve done. It’s been really cool. So if somebody’s listening and they want to learn more about maybe Visual Terrain and connect it all online, is there somewhere they should go?

David Green: www.visualterrain.net.

Dan Heaton: Excellent. Well, David, thanks so much. It was a blast. I really appreciate you being on the show.

David Green: Thank you so much for having me. I really enjoyed it. It was even more enjoyable than I expected. I really just enjoyed reminiscing and chatting with you. Thanks so much.

This post contains affiliate links. Making any purchase through those links supports this site. See full disclosure.

Leave a Reply