Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Rick Barongi was one of the key figures in bringing Disney’s Animal Kingdom to life in the 1990s. As the top animal executive for the creative development, planning, and construction of the park, Rick played an important part in making it successful. His role helped to ensure that animal care and conservation remained at the center of Disney’s mission. Rick is my guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast to talk about his background and work on Walt Disney World’s fourth park.

During this interview, Rick describes what interested him about working with animals going back to early trips to Africa. He worked at the San Diego Zoo when Disney contacted him about their secret project. His early work as a consultant ultimately led him to a full-time position as Director of Animal Programs for all of Walt Disney World. Rick collaborated with Joe Rohde’s team of Imagineers and developed an advisory board of experts. Another big milestone was creating the Disney Conservation Fund in 1995. We talk about why those conservation efforts remain such an important part of Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

Rick also relates stories from the park’s development including touring the site with Jane Goodall. We also talk about his work on Disney’s Animal Kingdom Lodge several years later. His next role was Director of the Houston Zoo, and Rick explains what interested him about helping that park evolve. We conclude the podcast by talking about Rick’s current work at Longneck Manor in Texas. The personal encounters with giraffes and rhinos there help to spread his conservation mission. I really enjoyed learning more about Rick’s work on Disney’s Animal Kingdom and beyond.

Show Notes: Rick Barongi

Learn more about Rick’s work at Longneck Manor on their official website.

Discover info about the Disney Conservation Fund and their latest efforts.

Follow Longneck Manor on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.

Support the Tomorrow Society Podcast with a one-time contribution and buy me a Dole Whip!

Transcript

Rick Barongi: The future is going to be this balance, the entrance to that. When you’re small, you’re not going to go on safari. You’re going to go like I did to the Bronx Zoo. Now you’re going to go to much better facilities, and I think if you present it in the right way and you can see that these animals are well cared for and exhibiting naturalistic behaviors, then I think we have a chance of getting the world to see that we need nature more than nature needs us.

Dan Heaton: That is Rick Barongi, former Director of Animal Programs for Walt Disney World, including Disney’s Animal Kingdom. You’re listening to the Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on Episode 188 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. Welcome back to 2023! I have a lot of fun shows. I’m looking forward to bringing to you this year, starting with this one with Rick Barongi, who was the Director of Animal Programs for Walt Disney World from 1993 to 2000, which included working very closely on the development and design and everything involved with the animals and wildlife and conservation with Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

That is the focus of our show today, is to talk about how Rick started consulting with Disney on a new secret project working with Joe Rohde and the Imagineers, bringing in an advisory board of experts and then acquiring the animals and finding the way because the Animal Kingdom functions as an entertaining theme park that we enjoy as guests, but also must focus on animal care and conservation through the development of the Disney Conservation Fund.

At the same time in the ‘90s, Rick played such a key role in leading the charge to ensure that animal care and conservation were a focus on this park, and he has a lot of great stories from the development of the park and cool background. Really thrilled that I got a chance to talk with them, and I think this is a perfect way to start 2023. So let’s get right to it. Here is Rick Barongi.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Rick, thank you so much for joining me on the podcast.

Rick Barongi: Oh, thanks Dan. It’s a pleasure to go down memory lane with Disney.

Dan Heaton: Oh, definitely. I’m really excited to dig into so much of what you did there and in other places. And I’m curious just upfront too, I mean, when you were growing up, I mean, how did you originally get interested just in wildlife conservation and even in working with animals as a career?

Rick Barongi: Yeah, I’m asked that quite often, and there wasn’t one moment in time that “Aha!”, I want to do this, but it’s a combination of things. I’m a New York City kid on Long Island, and growing up I had a dog and no siblings, and then I went to the Bronx Zoo in field trips and the American Museum of Natural History, and I think all those things combined made me gravitate towards animals and especially Africa at the American Museum of Natural History. They had these incredible dioramas and jungles and volcanoes and it just looked like a cool place to go.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. So when did you decide then from doing that with animals in Africa that, okay, I want to go work in this field because now it’s a little more common, but it’s not always the most common thing people decide to do?

Rick Barongi: Back when I was in elementary school, we’re talking in the early ‘50s, late ‘50s, and early ‘60s. You had a guidance counselor, you go meet with your guidance counselor and they’d go, Ricky, what do you want to be when you grow up? I would say, well, I don’t know. I like animals. Oh, you want to be a veterinarian? So I geared my whole career to be a veterinarian, and I went to Cornell undergrad and then I applied to vet school and I got an interview, but I didn’t get in.

Then I went to graduate school for a PhD and I decided to get out with a master’s all along thinking I wanted to be a vet. But then I went to Africa during, in that time between undergraduate and graduate school, and that changed my life and I said, no, I don’t need to be a veterinarian. I want to work with wildlife, and there’s so many different ways to do that. And then I started working at 21 in a safari park and did that ever since I retired from the Houston Zoo. Well still do it now at Longneck Manor. Now I have rhinos and giraffes outside my back door, which was my dream all along.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I mean, that’s impressive. We’ll definitely dive into that too. Well, I know you mentioned you started working at a wildlife park and went to the Miami Metro Zoo, and then ultimately you became the curator of mammals at San Diego Zoo. So how did that evolve as you went along, what you were really interested in doing or has your career moved in those kind of early years?

Rick Barongi: Well, I think once you get a lot of it’s opportunistic and just chance. So I started working safari parks with in a Jeep with large cats and bears, and then I went to San Diego and worked with hoof stock and I said, antelope, all these antelope species that turned out and rhinos and giraffes. That turned to be even more challenging in a way because with the dangerous animals, you’ve got bars between you all the time, but with hoof stock, you’ve got to worry about them getting injured too.

So I really became a hoof stock person, which is an antelope type person, and really appreciated that as a keeper at the San Diego, it was called the Wild Animal Park, and now it’s called the San Diego Safari Park. That was really enjoyable. And then from there I went to Miami as curator. Then I started managing people. Working with the animals was easier than managing people. The animals, they say they’re unpredictable, but once you get them trained, they’re very reliable. Once you get people trained, that’s not always as reliable. So then I just went up the chain of command and it was more people management than animal management.

Dan Heaton: So ultimately then you become more of a people manager, but I’m sure you’re still involved, you’re Curator of Mammals at San Diego. And then at that time, there’s a small team at Disney that is starting to get involved with Joe Rohde leading it in the early nineties and working on a project that was very secretive. So when you’re at that point and you start consulting with them, how does that work where you ultimately then become a consultant for this project that at the time probably seemed like it might not even happen?

Rick Barongi: Yeah. Well, again, here’s a story now, but it’s opportunistic. I’m sitting at my desk at San Diego Zoo. I was at the zoo, then Curator and Director of the Children’s Zoo too. And I get a call on the phone from the main office at the zoo saying, there’s a guy at Disney that wants to speak to you, and I pick up the phone and it was Joe Rohde or Joe Rohde’s assistant, I forget now. And they said, hey, we’re working on an idea that’s very confidential at this point, but your name was given to us. Would you be interested in helping us? Said we’re very secretive.

I said, well, yeah, I guess so. I said, well, can you come up to Burbank up and everything’s done in Burbank and Glendale? So I did and learned that they were planning something with animals in Florida. So I went back to my boss, the director of the San Diego Zoo, Doug Myers at the time, and I said to Doug, Disney is asking me to consult. Well, they asked me to come back then they were more interested in me, and I can remember Doug saying to me, what are they doing? I said, well, they’re doing something with animals. He goes, as long as it’s not in California, you can consult.

He was very dogmatic about that. Then, so I started, that was 1990, and I just started working with them, and I guess I found out much later that my mentor at the Bronx Zoo, Bill Conway, had recommended that they call me. He never told me that until years later. I thought they just called San Diego saying, well, let’s call the best zoo in the country and see if they got somebody we can talk to. I had no idea, but I owe a lot to Bill Conway for that, and Joe Rohde, then the head Imagineer.

We got along very well. I was open-minded, but I was practical about what they could do and what they couldn’t do. Joe wanted 100 wildebeests running around 100 acres. I said, Joe, it’ll be a desert in two days. You can’t do a hundred. He said, okay, we’ll do 10 and make it seem like a hundred. I said, that’s an Imagineer.

Dan Heaton: So yeah, I mean when you start this and you’re talking to Joe now is so well known, but at the time was fairly young. And what was that like? You just mentioned that story, but just his energy and then him coming at it from kind of this Art Director/Imagineer approach, thinking of it very differently, I’m sure than you were thinking of it coming from as a Curator at a zoo.

Rick Barongi: Yeah. This is when I started realizing, Hey, I kind of can be a little creative too, not an Imagineer. They called me an honorary Imagineer, but Joe would take, their approach was so different. They would develop the concept first with renderings, and we just talk about, you used the word zoo. How can we be different than a zoo?

We’re going to charge a hell of a lot more money, a heck of a lot more money, sorry. And we can’t just be a zoo. Zoos are great, and every city is very proud of their zoo, but we’re a theme park. So we kind of focused in on three aspects of it. The live animal zoo, the extinct animal, and the imaginary animal. That was the three areas, the lands that we really started with the Animal Kingdom, and of course it was always Joe leading everything.

Dan Heaton: I think. I mean, it ended up coming together very well. So like you mentioned, it was very confidential at the time and secretive, but I know that then you started connecting with some other experts to advise during those early days. So how do you go about doing that when you’re having to not really say what it is or you’re trying to pick the right people to talk as this Advisory Board that ultimately came together?

Rick Barongi: Well, Joe was very open-minded about that, and so was Judson Green, who was the head of Disney Parks at the time, and Judson was very, even though we had to keep it confidential from the press, I could approach certain colleagues and what I told them, I was sitting in these meetings and I’d say something, oh, we can do this. We can’t do this. I go, wait a minute. You’re just going to do exactly what I say, and I’m the only animal expert in the room. I said, I need some of my colleagues here that may debate with me. You need to hear there’s more than one way to manage animals and exhibit animals. I said, I love it that you’re giving me carte blanche here, but I got to bring in some of my colleagues.

So I did brought in and we formed an advisory council, which Bill Conway, he didn’t have any time after I came on, but when I asked him to be on the advisory council along with Russ Meyer and a host of other people, that really changed the game because they set in on, they came several times a year and really gave lot of good feedback on how a for-profit park could also have a nonprofit conservation mission, a very strong environmental conservation mission, which is even stronger now, but I have to give a lot of credit to that advisory board. They were very passionate. We handpicked them, Joe and I, and that’s how the Disney Conservation Fund was born with that group.

Dan Heaton: Well, yeah, and that’s something whereas a legacy of the park, even beyond just the specific attractions, it’s that element. So I mean, I’m curious to learn a little more about the Conservation fund, which does a lot of great work today and has for a long time. How did that come together and how important was that to you to get that started at the time?

Rick Barongi: This is really important. At that point in my career, early ‘90s, I had had a lot of fun working with animals as a keeper and working my way up, and I go to Africa a lot. I’ve been there over 50 times now, and you see what’s happening in the wild. We tend to focus on the individual animal here and welfare, but welfare in the wild is much more important and how animals are getting their habitats getting shrunk down, poaching, all the problems that they’re having in Africa and around the world.

So I said to Disney, I said, look, you’re going to get criticism for doing live animals. There are people out there that just, they don’t like the word zoo and they haven’t been in 20 years. Their image of a zoo is an animal pacing behind in a small space behind bars. There was a lot of pressure on Disney just doing an animatronic zoo, a virtual reality zoo, or whatever.

But we were going to do real animals. So I said, you better establish a track record of saving animals in the wild before you open this park. They bought that Judson got it, Joe got it, and said, well, and we use the Advisory Board and we have to give money out before. So when we announced the park, we had a 1995 press release, and at that point we had already committed millions of dollars to conservation, and I think that resonated very well with them, and it did take the wind out of the sails of most critics or potential critics of the zoo. There’s always some that we had to respond to so many letters of people because they got misinformation about what was happening.

Dan Heaton: That had to be a challenge because I mean, I think of the landscape now, but yeah, at the time, I mean, zoos have evolved so much in the past 25 years with the kind of exhibits they have and everything else, but at the time, and then Disney, they had Disney’s America, which didn’t end up working out, and so they were also kind of facing that. And then Disney has a reputation, just positive, done a lot of great things, but not with everyone. It’s like a family kind of children’s area. So I mean, it sounds like that was one big step. Were there other things that you were able to do to make sure that the, I mean, I didn’t hate to say PR, but that what the park was actually doing was out in the public?

Rick Barongi: Yeah. Well, we had to focus on animal number one and then conservation, the guest service side of it. Disney had that better than anybody, but we had to make sure that whatever we did, we did it better than anybody else, or we were cutting edge. And the back of house facilities where the animal spent time at night, the enrichment training, we hired some really good people that worked with these animals. I think Disney raised the bar for animal care and animal habitat design, both on show and off show for other zoos, and changed the perception of some people with the word zoo, it still has a negative perception.

I usually say zoological or zoological parks, because the good ones, there’s good zoos and there’s bad zoos, and I always say, I worked in good zoos and theme parks. If we focused on that and the individual, we told stories about the animals, which is great for Disney, a storytelling company. So they got to know them. They got to know that the keepers that worked with them cared for them just as much as they cared for their family, pet or their children. When a special animal died, we brought in a grief counselors. That’s all we could do. We could show them we’re going to make mistakes here. They’re live animals. They’re not Mickey Mouse. They don’t live forever, but when we make a mistake, we’re going to learn from it and we’re going to get better.

Dan Heaton: Well, I know around that time too, we mentioned you had been consulting, but you ultimately then took a full-time position at Disney overseeing all animal operations, which includes the Living Seas and Discovery Island and other areas at the time. What was it like for you to actually then decide, okay, I’ve been helping, but now I’m going to take this on full time, which I think was around the mid ‘90s, same timeframe?

Rick Barongi: Well, in some ways it was overwhelming, but then you had so much support. The Seas had some really good people already passionate about conservation and the environment and the oceans and the ranch too. And then we had Discovery Island at that point too, which is now, I don’t know what they’re doing with that little island nowadays.

Dan Heaton: Nothing right now that we know about.

Rick Barongi: Yeah, there’s always rumors about it, but it was a beautiful little facility, but it wasn’t going to work after we opened the Animal Kingdom. But mainly I still focused on, I had meetings and I was over all of that for a while, but we were still focusing on Disney’s Animal Kingdom and getting that open and hiring. I think we hired staff from almost 80 different zoos in the country.

I mean, when directors saw me, they tried to hide me from their best people where they would come to us and then we’d hire all these great good people, and they became even better Disney with the Disney resources, all the things that Disney does to make an employee a better person, a better manager, and then some of them actually went back to those zoos and leapfrogged up into management positions. So I mean, there’s no data on that, hard data on that, but I think Disney did a real service to the zoological profession in this country.

Dan Heaton: Oh, yeah. So I mean, now we get to the point though, where you’ve developed it, I mean, as it was developing and coming together. You mentioned the three different elements. How did it evolve the park itself? Because you mentioned that they had imaginary and everything else, but upfront it was mostly focused on Africa and Kilimanjaro Safaris in that area. Were there a lot of changes as it came together about what the focus would be early on?

Rick Barongi: Yeah, there always is. I mean, we had renderings up of safari experiences, and it was always about getting the guests as close to the animal as possible and still being safe, like a soft adventure. They had to learn about animals. I mean, the extinction side, the dinosaur rides and the imaginary stuff they had that. They knew that already by bringing in other people and then hiring people. We started planning that park in 1990.

So it did change the Imagineers’ original perceptions to some degree. We all made compromises to some, but we knew we couldn’t compromise on animal care and health, and we changed species and the numbers of species that were out there. The horticulture, the head of horticulture, Paul Comstock, was designing this incredible Garden of Eden, and I looked at him and said, they’re going to eat all this, Paul. He said, well, we’ll just keep replacing it.

I said, well, yeah, you’ve got the budget to do that, but they’re going to eat it faster than you can replace it. So I can remember looking at ’em and said, that’s just going to be a salad bar buffet for the animals, Paul, you’ve got to protect some of this stuff. So we’ve figured out clever ways to protect some of it, but Disney, they didn’t mind that the animals were eating the habitat and zoos.

They didn’t like that. So I learned from them that, don’t worry about that, Rick. We’ll take care of that. We’ll still make it look good by the next day. I said, okay, if that’s what you want to do. Again, they were thirsty for knowledge about live animals, and they all wanted to do it, right. Nobody wanted to sacrifice it. We weren’t talking about, oh, let’s have babies because babies are cute and bring in the public.

We had an interesting discussion about giant pandas. Should we get giant pandas? And we agreed, no. I mean, everybody kind of symbolizes that as the flagship animal of any great zoo, but we didn’t need that. It was the whole story. It was the experience itself. So instead of putting giant pandas at the entry, which some people wanted, we said, no, we don’t need that.

We want to immerse them in this habitat. We want them to leave understanding the whole story and not have a checklist and say, well, they don’t have giant pandas. They don’t have this. They don’t have that. No, we have animals that together as a group will impress you more and enrich the experience. So there were a lot of philosophical discussions that we had at the beginning, but nobody pushed back. Everybody wanted to do what was responsible for the animals. That always came first.

Dan Heaton: Oh, definitely. Well, you mentioned choosing the animals, and then I know you were involved with acquiring the animals. I think about if you went and worked at a zoo which was already in place, you might be acquiring for a certain area, but you have to basically populate the entire park. So I mean, what was that process like to go deciding on the animals and then ultimately acquiring enough animals that can fill such a big space?

Rick Barongi: Well, first of all, we had to get a separate offsite holding area because you couldn’t bring ’em all in at the same time, and they had to be acclimated. So two years in advance, we were acquiring animals at a separate facility that was quite a distance away, and we built more facilities there, and we had keepers working out there. That was for most of the hoof stock and then other animals like elephants. No, you couldn’t hold them any place.

You had to just bring them in, and elephants was extremely controversial. That’s a whole ‘nother story. We were going to rescue a family out of Africa that was going to be called, but then we decided not to do that. We got a lot of criticism, and then they put a moratorium on culling, and so the group that we were going to get was not going to be called.

So then we couldn’t justify them coming in. So we brought in African elephants from different zoos, and it worked out. Hippos was another very challenging area because hippos are very social, but they grow up together. They don’t just be put together, and we found out that by getting young hippos from a bunch of different zoos, they bonded right away. They wanted to be with each other, but we built a lot of holding space there too, just in case we weren’t sure how they were going to get along. Nobody had ever done a hippo exhibit like Disney. That was really a game changer for that species.

There’s a lot of stories like that. And then we also had Jane Goodall involved at the beginning, which was really important. I met Jane in LA, I guess it was like ‘90, ‘94; I knew her executive director of her, Jane Goodall, JGI, Jane Goodall Institute, and he put me in touch with her, and I’m sitting at my desk one evening, I was working late, and the phone rings and she goes, hello, is this Rick Barongi? I said, yes. She said, this is Jane Goodall. Of course you recognize the voice, the first word. And I said, yes, I know.

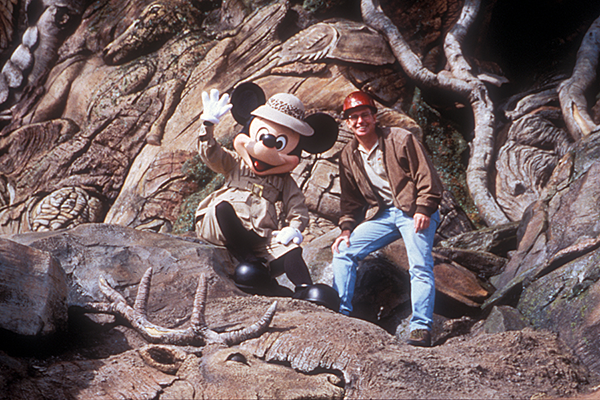

She said, I’ve heard a lot about what you’re doing and I’d like to meet you. Are you available for dinner tonight? I said, yep. So it was her and her lifelong executive assistant, Mary, who’s incredible, Mary Lewis, the three of us had a dinner, invited her. We had a great time. We invited her to see the park. All the Imagineers were lined up. I mean, it was top secret, but it was Jane Goodall, so nobody cared. This was at the bowling alley. It was where we had the models and everything, and we showed her everything that we had at the point, and then I took her out, not at that point, but a year when we started construction. There was a great relationship with Disney at that point.

She was very, and she’s not a big zoo fan, but if it’s a good zoo and a good facility, she will help. So when we were building the park, this is the story that I tell a lot. I haven’t written it down yet, but we’re building the Tree of Life and it’s 150 feet tall, and they have a platform of about 100 feet. They called it the dance floor at that point, they had a lot of the carvings done. The head car jolt was incredible.

So on the tree, we climbed up to there, which would have never been allowed to take somebody. I wasn’t even supposed to go up there. And we had hard hats on, and we are looking around because Jane was great. I mean, Jane was probably in late 60s at that point, but she scampered up there. Jane’s incredible, and she just loved it.

She’s looking at all the animals, and then she turns to me and says, Rick, there’s no chimp on this street. There’s wild geese; there’s everything from Africa elephants, there’s everything. There’s not a chimp. She says, there’s a monkey like animal over here, but there’s no chimp. So I said, oh, yeah, I think you’re right, Jane. So I went back to Zsolt. I didn’t even know who he was at that point, but Joe Rohde’s assistant Jennifer said, you need to talk to Zsolt. So I said, can we get a chimp on the tree? Is it too late? So he says, well, send me a picture.

So I gave him a picture of David Graybeard, and about a month later I called him. I said, Hey, did you ever do anything with that picture? He says, come on down. He shows me this life-sized David Graybeard at the entrance to the bug show, right, with it’s arm out fishing for termites. It was just amazing. And of course, that was a secret that Mike Eisner showed to Jane when we opened the park, and Zsolt deserves a big shout out for doing that, and we really surprised Jane. Not only did she get a chimp, but she got her favorite chimp bigger than life, and right at the entrance, it was perfect.

Dan Heaton: Oh, that’s amazing. Yeah. Did you hear from her about the park? I know she was like an advisor, but I mean, did she have some thoughts about the park or what she liked about it?

Rick Barongi: She was an unofficial advisor. She was not on the Advisory Board, but we just used her. We had her there during the press event, and she’s there and she says, I’ll handle the European press, because she knew we were doing it right. So she then developed relationships with a lot of people at Disney after that, but the entry to Disney, and she still has a very close relationship with Disney to this day. So it really worked out well for her and for Disney especially, to have Jane Goodall associated with the opening of the Animal Kingdom was you couldn’t have a better person. She’s the only household name in conservation.

Dan Heaton: I want to ask you a few things more about Kilimanjaro Safaris and that, because that’s such a complicated space to do an attraction. What were some of the, I mean, because I’m sure there were challenges about which animals could be in which place and how they could connect. What was that process like to work with Disney? They were putting together this attraction, but you’re also having to think of it in terms of here are all these different animals you referenced, elephants or hippos and others that all have to kind of connect in a way.

Rick Barongi: My background was a lot in safari parks and hoof stocks, so this was my bread basket. So I knew what animals you could mix together. Elephants had to be separate, obviously, and they look like they’re part of making the boundaries invisible. So it looks like everything’s together, but they’re really not the concept of bringing most of the animals in at night and then bringing ’em back out in the day to save on the habitat and get them trained.

So you could do that if you needed to look at them closer. And of course, we hired some really good people to do all that. I knew what had to be done, but I needed the people to develop those steps. And the designers too had to, I mean, we went through so many renditions of the slope where the giraffes had to walk up to get to their barn because the whole safari has a berm around it.

They brought in, I mean, it was a flat space, and they brought in so much, so much dirt to make this, I don’t know, 10 foot or higher berm around the whole property. But the giraffes had to go over the berm and then into their barn, which was hidden, and that’s a tall barn for giraffes. It’s over 20 foot tall. And so we had this slope and we kept debating was it too steep?

And it kept lowering it, lowering it, lowering it. The Imagineers did a skit one time, and they made fun of me actually, because it kept changing our mind. The drafts could make it when it was steep, but an older draft maybe not so be safe, rather than, sorry, we finally almost leveled it. But they had this skit where they had a guy in a giraffe outfit and they had this little ramp and he wouldn’t go up it this puppet, and they kept throwing money down, and finally they threw enough money down. He went up the ramp. So at the time, I didn’t think it was so funny, but I do think it’s funny now.

Dan Heaton: Oh, that’s great. A lot of animals, it seems like at least don’t like to come out during the middle of the day, whether it’s hot in Florida, as you know, is very warm. So did you have to use some tricks to kind of with shade or with different enticements to keep the animals in view basically?

Rick Barongi: Well, it’s not tricks as much as it’s just the common-sense animals like shade, especially in the hot sun. So you put as much shade as possible closer to where the road is that the vehicles are on, and you put feeders close, and they’re still pretty active. They’re animals that are acclimated to that kind of heat. If it’s really hot out, they’re going to lay down in the middle of the day, and people know that. They know the safari is probably more active in the mornings and in the late afternoons than it is right in the middle of the day. But even in the middle of the day, they’re still going to be visible.

So I mean shade and where you place the feeders and the water was always key, but the animals love to be outside rather than to be inside. With mixed species exhibits, you get a lot more activity than if you just have one species out there, other animals are walking by, so there’s more enrichment, there’s more things to do.

They’re not so much chasing each other, but when they can see other things going on and their day isn’t the same every it’s, it’s not like Groundhog Day. Every experience is different. It keeps animals on their toes more. I think it’s better to keep them active and watching out for different things than just sitting there board. So mixed species exhibits and safaris I think are always more interesting than just an exhibit that just has a few animals in it. And you can make that exciting too, but not like a safari in itself is if you have enough of the right ratios of the animals out there can be very, very special.

Dan Heaton: I’m curious, you mentioned the elephants and the challenges because that space really large with the watering hole and then the Baobab trees that were created. What was that experience like putting that together or even maybe some challenges with doing it?

Rick Barongi: Well, elephants are one of the most challenging species to take and put into an artificial habitat if you’re going to do it. You have some people that think that there’s no amount of space that is sufficient for elephants unless they’re in the wild. In the wild. They’re, they’re contained too by barriers. But it’s not so much the size of the space, it’s the quality of that space and the makeup of the very social animal needs. Different age group animals needs to be a breeding group.

They are so much more content when it’s a breeding group. But we did, we tried to do almost an acre per elephant, and there’s no hard, fast rule on that again. Then we had another smaller exhibit where we could put the bull when we wanted to separate him out. That and the hippos were by far the most expensive habitats.

I don’t like to call ’em exhibits because I think there really are habitats that mimic the wild, what they lack in space, they gain in the enrichment and the feeders and the training that the keepers do and the attention they get. I wish these animals could actually talk and tell you, Hey, this is a pretty good deal. Yeah, I’m not in the wild, but I’m also not running away from poachers and wire snares and things like that and raiding crops because I don’t have enough food. I mean, the wild’s, no picnic either. And I’m not saying I love going on safaris, but we had to put things in perspective better.

Elephants, I think we did it right. We brought in some really good people, elephant whisperers, I would call them, because you’re introducing different elephants together when we put ’em out in the habitat. And the barn was incredible too big enough so that we could work with several bulls and different females that may not have gotten along at first. So we put a lot of effort into the elephants, and I think it’s paid off. They’ve had a lot of bursts out there too.

Dan Heaton: Oh, definitely. It’s an amazing space. So I’m curious for you, what are one of your favorite habitats in that area or even in the park itself that you think really came together?

Rick Barongi: Well, the Hippo River exhibit is from a guest perspective, I thought came out really well with the artificial ruts. The dirt road on the whole safari is, I always call it the most expensive dirt road in the history of civilization because it’s not really dirt, it’s artificial mud, mud and concrete. But I love that, that sense of just that small section of Hippo River that we recreated there, that I like the elephant exhibit two. I don’t really have a favorite other than overall, I think when you’re serving that amount of people a day, it’s very difficult to balance the needs of the animals, the activity and the people, and the safari, the look of it too.

It’s got to be one of the most beautiful in a hundred acres, which is I think what the Kilimanjaro Safari is. You make it feel like it’s much larger than that. That’s not my credit, that’s the Imagineers and the designers, but I feel very proud of what they did. I think we talked, Disney doesn’t like to talk money, but it was millions of dollars an acre just to design the safari, and they never questioned what we needed out there. So the lion exhibit also, it is designed in a way, you don’t see the moat and making the barriers invisible. Disney again took that to the next level.

Dan Heaton: The lions are sometimes up on the rocks, and it looks like they’re really close and it’s really neat effect, which I know is not as close as it looks. I also love the walking trails too; I know you were involved with the first one, which is now called the Gorilla Falls Exploration Trail, putting gorillas in place. I mean, I’m curious how that came together, just given that, I know gorillas aren’t always easy to have in a habitat.

Rick Barongi: I’m glad you brought that up. Gorillas is one of my favorites. It’s two exhibits. We did one for bachelor males and one for a family group, and they could see each other, but they didn’t have to see each other. But to get a family of gorillas was challenging, to say the least at that point in the zoo profession, they all had to come from other zoos, obviously lowland gorillas.

We ended up making agreement with the Lincoln Park Zoo because they had two groups and they could move one of the groups, and it wasn’t, you needed official recommendations. Other zoos were waiting in line for gorillas, but we were able to take a whole group at once and also make a significant country. You don’t buy gorillas, you don’t pay money, doesn’t exchange hands. But we worked with Lincoln Park to do more conservation of gorillas in the wild, and in return, we got this family with, Gino is a silverback.

I think he’s still out there. I hope he’s still out there. He’s pretty old now. But he was hand raised in Rotterdam as a youngster and came to Lincoln Park, and then he got him at Disney. Having a family of gorillas that close and already acclimated to people, they came into a bigger habitat than they had, was very satisfying. And that animal acquisition was the toughest one, because it was tricky because every other soup was waiting for gorillas too. But they went with, well, Disney’s got this incredible exhibit, and they’re doing more for conservation. So we went to the head of the line. Some people didn’t like that, but it was the right thing for the gorillas.

Dan Heaton: Well, I know you also were involved at least in some fashion with the Animal Kingdom Lodge, which came a few years later. But I found to be a very cool resort, another way to see the animals in a different fashion. But it seems really cool to me, and I’m curious if you have any memories of working on that cool resort.

Rick Barongi: Of course, that was really one of my last major projects with Disney. But you got to give Peter Dominick all the credit here. He’s passed away now. The architect, amazing guy, the lobby that he did, we took him on Safari. Joe was on that safari and a lot of people. But Peter, he had some other people with him. He designed this breathtaking lobby. I love that. I guess my contributions were a couple on the balconies. People were saying, well, don’t we want to screen ’em in because the animals will attract flies? And I said, no, that’s not anymore. They’re ruminants. This isn’t.

It’s like cow pasture. It’s not a lot of flies. You don’t put screens on the balconies. And then they wanted to go, I don’t know, higher, several stories higher because more rooms, more money. I said, you’re too far away. We compromised. I wanted three stories. Then you had to have a fire road between you and the animals, so you were even further away. But then they have the overlook in the other areas. But we got a lot of inspiration from that Africa trip. We went to some incredible places in southern Africa, and then Peter Dominick did his magic with his people, and it’s a special place.

Dan Heaton: Oh yeah. It’s the most beautiful resort at Disney World for sure. If not almost anywhere, with what he did with that. Well, it’s crazy to think the Animal Kingdom is celebrating. It’s going to celebrate 25 years next spring. I’m curious for you, based on your experience, I mean, what do you think is the legacy of the park or what kind of stands out to you that’s something you’re really proud of from that park that you were involved with?

Rick Barongi: Oh, without a doubt. It’s the conservation commitment and the way that’s grown under Mark Penning and Claire Martin that run it now. It’s unbelievable where there are over a hundred million dollars or way more than that, I think, for conservation in just 25 years. I know that’s a lower number.

Claire would correct me on that. But putting that Advisory Board together and giving me free reign to do that, when like you said, it’s a very confidential park. And having the Advisory Board meet with Michael Eisner at the time, and he met with us. Roy Disney was sitting next to me in most of these meetings. Roy was a special person. It was like sitting next to Walt. He looked like him; he talked like him. He was his nephew. Roy was such a sweet person and so passionate. He said, Rick, the best thing of my time at Disney was when I was doing the True Life Adventure films.

I just loved the nature films. And Roy was so special, and Michael bought in. Everybody bought in, even though everybody said, oh, it’s Disney just wants to make money. No, they have social responsibility big time. It is that conservation commitment. Sure, we get a lot of people coming there, and they have, and it’s probably influenced a lot of young children to go into biology and conservation.

That’s really important. But I think just helping animals now instead of waiting for the next generation because later is too late. We’ve got to work on that now and Conservation Station that we didn’t talk about that so much. That was really important to continue the story that, hey, yeah, these animals that don’t worry about our animals, we’re taking really good care of ’em, but their counterparts in the wild need help. So that Disney Conservation Fund is probably the thing I’m most proud of being part of and helping to create that.

Dan Heaton: Well, you mentioned Conservation Station. Yeah, I mean, I’ve been there when they were doing a surgery there and people were standing and watching kids and everything else. And to me that up close view through a screen that people can have from anywhere, people coming from around the world is really, really powerful. Something that I think probably like you said, is going to make a big impact.

Rick Barongi: That’s a quick funny story too. And others, I suggested it, but other people had done it putting a window in the operating room of the vet hospital. We didn’t have any vets at that time. If I had vets, I said, no way. We’re going to do this in front of the public. But I can remember after it was done, Dr. Mark Stetter said to me, Rick, he said they love it and we’re fine with it now.

Now he’s the Dean of the UC Davis Vet School, Mark Stetter. He was the head vet at Disney before Mark Penning and the other people that run it now. And Mark would laugh, he said, yeah, but you’re right, Rick, if you had come to us early on and said, we’re going to do this, no way, we want the public watching us. But he really brought into it.

Dan Heaton: That’s funny. Yeah, I even think about it. I’m like, wow, it’s really cool they did that. I wouldn’t expect it. So it’s funny that the way it came together.

Rick Barongi: I kept emphasizing and other people did too. We have to be transparent. Don’t be like zoos used to be, say, you don’t show ’em what you’re doing behind the scenes because 90% of what goes on in a zoo is behind the scenes and it’s the most interesting stuff. Show ’em cameras, show ’em what we’re doing behind the scenes. Do VIP tours. There’s nothing to hide in what we do in a zoo. And if you can be transparent, you’re going to be alive.

Then if something happens, you can explain it and say, well, this did happen. An animal got injured or something worse happened, but this is the reason it happened. And it’s something that we can fix and learn from or it’s something that just happens. Animals in the wild kill each other once in a while too. Transparency, which was also a difficult concept for Disney when they got tunnels and they got characters where you can’t see ’em outside of their costumes and stuff. So maybe transparency was the biggest challenge sometimes with Disney. We’ve got to be really open here, guys. You can’t hide anything.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I mean it’s all magic. That’s how they present things for a good sense in a way when it’s talking about other things. But here, I mean, now they even have a TV show where they show a lot of what’s happening at the Animal Kingdom on Disney Plus, which I think is great because it’s like anything you can show behind the scenes. People love that. People are really into it. Well, you ultimately did leave Disney and you became Director of the Houston Zoo, and I’m curious what interested you about taking that role as that zoo was growing and then as you look back, what you were excited about from you were able to do there.

Rick Barongi: Well, Disney taught me a lot a heck of a lot more. And it taught me about where I think I’m stronger. I’m stronger at the front end of a project, the blue sky side and the vision side. I learned that from Disney. And then when it’s more of a maintenance, which is not easy by any means, I like to keep growing. So Disney’s Animal Kingdom was done, and Houston offered me an opportunity. It was a city zoo, city run zoo that was in a good location. It had good people, but it was city run and it was just running in place. They never couldn’t make improvements.

It was charging like $2.50 for a ticket. So I went from a facility that was charging, I don’t know, $50, $40 a person to $2.50, but I knew if we privatized the Houston Zoo, got it, the city could still own it, but they didn’t manage it. We could grow that zoo. That’s why I chose Houston. It was a fixer upper. It had a lot of potential and I thought I could help. And we did. We got it privatized in two years, and then it’s now one of the best zoos in the country because of other people that are leading it now. And it also has one of the best conservation programs. Again, conservation to me, animal care and conservation are the two cornerstones and guest experience obviously are the three cornerstones of any good zoological park.

Dan Heaton: Well, I know you now are working at Longneck Manor, which I would love to learn more about. It’s more of a personalized experience, but I think still fits really well with the message you’re trying to give. So I’d love to know some more about when you decide to do this after retiring from the Houston Zoo.

Rick Barongi: I think it’s my passion from Disney from all the other places that I worked, San Diego, I worked in big places, Houston, they all had millions of people a year, Disney, even more than that. But I wanted to do something smaller and reach guests even more individually and really touch at their heartstrings. That’s what Disney taught me. It’s not about telling people, you got to save this animal because it’s being shot, it’s being killed, and we’re losing this many all the time.

You’ve got to tell the good stories and you’ve got to personalize it as much as possible. For me to do that, I wanted to do it in a smaller venue and more immersive and more stories. That’s what we do at Longneck Manor, which is a nonprofit conservation park. That’s what I call it. We focus on two species mainly, and that’s rhinos and giraffes.

Two of my favorites, giraffes, because everybody loves giraffes. I’m finding out that it’s a spirit animal of a lot of people. It’s right up there with elephants and the major animals, little kids. I guess I identify that silhouette of a giraffe before anything else. And I do like giraffes, but rhinos have always been my passion. I’m very involved in rhino conservation on boards and the International Rhino Foundation, which is a great organization. My wife and I both sit on that board, and I didn’t mention my wife or a life partner, Diane, who also worked at Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

She worked in the public affairs, not at the Animal Kingdom because she came from San Diego also. But the Longneck Manor was something I’d been thinking of for maybe 20 years or more, and I figured if we could have people learn more about these animals and do longer tours with them, I mean, sure, you can feed a giraffe in most zoos, but you don’t get an hour and a half with just a small group of people, 10 people or less, or one family.

Sure you get to feed the giraffes and scratch the rhinos, but it’s much more than that. We show ’em the facilities; we talk about how the animals got here. We talk about conservation. I have a nonprofit conservation foundation that after the tourist people, after they pay a hundred dollars for a tour or a lot more money for the overnight, they make extra contributions. So I’m reaching a smaller number of people, but I think I’m reaching them much more deeply and again, touching at their heartstrings, which is what Disney does, get people to care first.

Then you can go to appeal to the head. I call it the three Hs, the heart, the head, and the hand. You go to their heart first. Then you educate them with the head, and then they’ll lend a hand whether it’s a donation or they become more interested or take a career. I wanted to do it on a much smaller venue, getting old. I’m 70 years old and personalize it, and it is working out that way. The overnight is the real special thing. We have one, it is like Disney in the castle. I think they have a room way up on top of the castle. Do they still have that?

Dan Heaton: Yeah, they don’t bring it out much, but I think they still…

Rick Barongi: It’s still there, but even we don’t know about that. But I built a three-room suite on the second level looking into the main giraffe stall. So at night, when the drafts come in, because they come in every night, you don’t want to risk drafts out at night with lightning and stuff, especially lightning. So when they come in at night, there’s these three large windows in each of the rooms, the living room, the kitchen and the bedroom, and they can just watch the giraffes all night long. The lights go out after 10 o’clock, but they sleep with the giraffes and that they’re in the barn, but they’re in a separate luxury facility looking out at the giraffes. So we brought ’em as close as possible.

And that thing is that suite, the Giraffe Suite is booked almost every single night of the year for the next two years, ‘23 and ‘24. And because it’s only one suite, so we’re going to build some cottages next year in a welcome center, but I don’t want to get too big. I’ve worked in big places and big places are great, and Disney’s amazing the way they can personalize the experience for every individual, but I can do it even more effectively with a smaller group of people.

Dan Heaton: It reminds me of Animal Kingdom Lodge, but taken to kind of the next level where you’re able to, they’re not so far away and you’re able to get really close. Well, I mean you’ve seen it with zoological parks and everything else that they’re trying to bring you closer to the animals and have those personal experiences. How important do you think that is to the future of conservation and getting people more interested in helping out Just that personal side of it?

Rick Barongi: It’s more of a question of how do you see the future of zoos with all this virtual reality stuff where you can almost now feel like you can feel the breadth of the animal. You can feel like you’re petting the animal when you’re not. The illusion of quality is greater than quality itself. That’s a scary sentence. It came from Carl Hiaasen book, but are we making the artificial experience better than the reality? You’ve got to have a balance there. The real is not edited, it’s not scripted.

Bringing people close to the animals without disturbing the animals like giraffe feeding is a win-win. Giraffes like to be fed. It’s just lettuce, romaine lettuce. It’s not harmful to them. The public gets to feed ’em. They’re a relatively safe animal. You’re not around their feet, so they’re pretty safe. But the future is going to be this balance, the entrance to that.

When you’re small, you’re not going to go on safari. You’re going to go like I did to the Bronx Zoo. Now you’re going to go to much better facilities. And I think if you present it in the right way and you can see that these animals are well cared for and exhibiting naturalistic behaviors, then I think we have a chance of getting the world to see that we need nature more than nature needs us. If we destroy nature, we’re not going to survive. And that long-term thinking isn’t that long-term. Don’t get into complex issues about climate change, but just get them to care about animals and see if they’ll take those first steps and then learn more.

Nobody can predict the future and everything changes so fast nowadays. I don’t really have an answer other than take good care, do the conservation. These habitats have to be as naturalistic as possible with invisible barriers. If we can have force fields like in Star Trek, that would be great. And holograms. Jane Goodall is talking to everybody right there about her chimps and stuff. That would be fun.

Dan Heaton: Maybe in the future. Well, I’m curious. This has been great, Rick, but is there a good place people can go to learn more about Longneck Manor and what you’re working on?

Rick Barongi: Yeah, yeah. I mean, longneckmanor.com is our website, and you can learn. Learning for us is coming out and experience the facility, and then we get to other conversations. All my staff has worked in other places, and eventually all of them will have been to Africa. I want to promote Africa. I want to get people to go to Africa, not just to come to Disney’s Animal Kingdom or Longneck Manor, but I’m not better than any place else.

We all serve a purpose. We all work together. Disney does such a better job of connecting afterwards. They have this Explorers booklet now that they use that really is great, what they developed for kids to take a little steps first in their backyard and learn more about animals. They do that so well, and I learned from Disney too. You take somebody else’s idea and just do it better.

Don’t reinvent the wheel. That’s a lot of what we did. That’s a lot of what we did at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, and it really set the stage for what I want to do now as I get older, they’re just going to prop me up and I’ll just tell stories about Africa, I guess as I get older here. I’m really grateful that there’s been a lot of ups and downs in everybody’s career, especially mine. But I’m really grateful where we’re at right now. I think we’re reaching people, and it’s in a Texas Hill country along that manner. It’s very close to Austin and San Antonio, but it’s in a beautiful piece of property, over 100 acres, and so we have space to expand and we may get a few other species, but it’s not about the number of species, it’s about the quality of the experience.

Dan Heaton: Definitely. Well, Rick, this has been amazing. Thank you so much for being on the podcast and talking with me. I really enjoyed it.

Rick Barongi: I did too. Thank you. Appreciate it.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s going to do it for this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast. If you’re interested in what Rick’s doing, longneckmanor.com, really interesting stuff. I would love to make the trip out there to see the giraffes and rhinos and everything he’s doing as a more personalized approach to what he did at Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

Leave a Reply