Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

One of my favorite conversations on this podcast happened two years ago. My guest was Rick Harper, the director of Impressions de France at EPCOT Center. That incredible film was an opening day attraction in 1982 and still plays today. Rick was kind enough to talk about his work on that movie and his career. He’s also been a great friend to the podcast and connected me with other amazing guests.

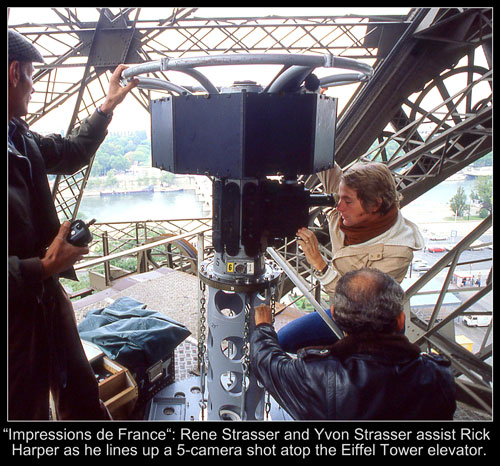

On this week’s episode of the Tomorrow Society Podcast, Rick is back to talk even more about his beautiful movie. He delves more into the technical challenges of shooting helicopter footage and other tricky scenes with simpler technology. It took inventive thinking and innovations on the spot to make the attraction work. The fact that it still charms so many guests today just reinforces the creative success of Impressions de France.

Rick also worked directly with many legendary Imagineers during his time at Disney and beyond. His stories about Marty Sklar, Harper Goff, X Atencio, and more aren’t just about the attractions. On this podcast, Rick tells so many fun tales about working at Imagineering. He describes the development of World Showcase pavilions that never happened, doing voice work for Space Mountain, and a surprising moment in the Everglades shooting speed room footage. Rick had a remarkable career, and I loved having the chance to hear more stories about his work.

Show Notes: Rick Harper

Listen to Episode 61 of The Tomorrow Society Podcast: Rick Harper on Impressions de France.

Watch Impressions de France in this HD version from Martin’s Videos.

Read my tribute article to Impressions de France on this blog.

Support the podcast through a one-time donation and buy me a Dole Whip!

Transcript

Rick Harper: This situation involved about six of us reading from a script that X had done, commander X 1242, we need to eject such and such hatch, and it was all this kind of jargon and we get a little ways into it and everybody just needs to be doing fine. I think I’m doing fine. And X looks at me and says, Rick, you’re terrible at this. I said, well, X, I warned you. He goes, oh boy. So we kept going, and much to my surprise, anytime I went on Space Mountain, no matter which park it was in, I always heard myself in there. Ann would point it out to me as well. So I guess he decided differently at that point.

Dan Heaton: That is Rick Harper, director of Impressions de France, who’s back to talk more about that film plus a lot of great stories of what it was like to work with so many Imagineering legends. It’s going to be fun. You’re listening to The Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on Episode 120 of The Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. Hope you had a good Halloween, even with it being so different this year. I am thrilled about today’s episode. It was amazing to get the chance to talk once again with Rick Harper, the director of Impressions de France. He’d done so much more. Rick was one of my early guests who had actually worked for Disney backed in Episode 61. About two years ago. I talked with Rick, had an amazing conversation, learned so much about his career and especially about Impressions de France. We’re going to dig even further in this episode.

He talks more about some of the challenges with shooting that film, given the technology they had at the time. And beyond that he spent a good amount of time telling some great stories about working with so many imagineering legends that were still around in the 1970s and ‘80s, like Harper Goff, Marty Sklar, X Atencio, like you heard of that intro clip. Even Gordon Cooper, the astronaut who was involved with Disney during the time before Epcot Center and lots more.

Rick even had a story about an unfortunate mishap while shooting at the Everglades for the speed rooms at Disneyland’s People Mover. There’s so much there, and I really appreciate that Rick was willing to come back on and talk once again. Well, I don’t want to waste any more time talking now because this is a long conversation with Rick.

I think it was just so much fun to do and I love checking in with Rick once again. He’s been a great friend to the show beyond just being on the podcast, super helpful in connecting me with other guests and just being a great friend to the podcast. Here he is once again, Rick Harper.

(music)

Dan Heaton: You mentioned being closely involved in the pre-show of Space Mountain and its installation, and I would love to know what it was like to work directly on that project. What was that like?

Rick Harper: It was a great opportunity. It was great fun as well, and I was in mean, working in the model shop was like being in magic land as far as I was concerned and all these wonderful talents there. And of course, Claude Coats, I think I mentioned him in the last interview. He took me under his wing. He got me involved with Space Mountain and eventually, for interesting reasons, he got me involved with the pre-show design. Claude actually had a condition in one eye where he couldn’t see, it may have been a cataract or some other kind of problem, and he didn’t mention it to anyone including his family.

But I noticed the way he had to kind of move and position himself in order to reach out and grab something like a pencil out of a desk drawer or adjust his lamp, desk lamp, he had to move back and forth the way people do when they can only see through one eye because they can’t quite perceive the three dimension of how far or close something is. Well, that pre-show involved a 3D effect that I could get way too technical describing how that worked. But Claude, it became very evident to me that he was having a lot of trouble with it, but he wouldn’t talk about it.

Claude was a very positive individual. It may have been because this eye condition was coming on kind of slowly, and he reached a point where he was kind of in that, where it was just blurry, not necessarily completely blind in that eye, but 3D was a big issue. So I noticed this and I started helping them with the achieving the 3D effect, which was complicated in how the objects had to be built and placed and lit so that the 3D effect would be maximum, and they were caused by a giant curved hemisphere that were placed behind the windows of that Space Mountain.

You may be aware, I don’t know what’s there now, but what was there at the time were about oh eight trapezoidal windows that as you were carried up on a moving sidewalk, so to speak, a moving ramp, these objects would appear to be floating by you and you’d go to reach and your hand had passed right through ’em. It was a pretty good effect. So I got so involved with that that he essentially just handed the design over to me and I worked under his supervision, which was of course a wonderful experience.

So he and John Hench and Marty made the decision to send me off to Florida to do the installation, which was an amazing experience at the time. Now you remember it opened in ‘75, I believe, down there. Yeah. So I went down there in late ‘73, I think, and I was there for several months working on this technical challenge. And it was a real challenge working with the construction crew because I looked like the California surfer kid that was still in my teens. I mentioned to you, I believe at one point before that I was famous for looking like a 15-year-old surfer.

So I show up and here are these crusty construction guys that were trying to drag the job out because they had been working on this thing for a long time, and many of these people had been working on stuff here and there ever since the beginning of the construction of Disney World. So they’d been at it for years and they saw the end of the money for them. They saw the end was near with this job, nothing was lined up immediately after it. So they were trying to drag this job out. They saw me and they said, oh, we can manipulate the situation.

So they went, oh, it just drove me crazy. And along with the attitude of who is this guy and what, who’s he? So it took a while to win them over. I did in a few ways, but they kept working on me. So I got together with a couple of other people that were down there. Marty Klein was down there working on the post-show installation, and there were several of us from WED down there working on different aspects of getting Space Mountain pulled together.

So we found that the best way to handle these guys that were slowing everything down was just tell ’em everything looked great. Lighting, for example, as I mentioned before, was extremely important on this pre-show to get the maximum 3D effect out of it. And so I had these very specific positions for the light and all of that for the different little lights, which were, by the way, the old incandescent Mole Richardson theatrical lights, which were extremely hot by the way to handle all day.

So I’d tell ’em, okay, well move, okay, now set it there. Good, good, good. Now tilt it up maybe 20 degrees. And they would tilt it 90 degrees and I’d go, oh, no, no, come back a little bit. They’d way overdo it. They’d overdo everything or underdo everything so that you give more and more and more. And they drag the job out minute by minute by minute. So I finally got to the point where I go, oh yeah, tilt it up a little bit. Oh yeah, great, perfect. Alright, yeah, just tack that down with, oh, no, no, no, you don’t need six screws, just use one. That’s fine.

We’d go on to the next thing. So then after working a 12-hour shift doing that, a couple of us from WED would go grab a dinner and then sneak back in at night and move everything in its correct position and put in the other attachments to secure everything and move on. It got more and more frantic as the deadline was getting closer where we’d just be working and we all got so exhausted. But that was how we got that accomplished. A fun occurrence.

One of the ways I got stress relief from all this pressure down there, they were testing the ride vehicles and I got to know the crew that was doing that pretty well, and they were putting sandbags in there to simulate the weight of the guests that would otherwise be riding these. They were just sending these things round, round and round around and they were testing on and on and on and on. So during the lunch break, I would go there and I’d ask ’em to just let one of the vehicles get into one of the vehicles in the load area, pull the sandbags out, I’d sit in there and I would just ride around and around for 30 minutes just over and over and over again. It was the perfect stress reliever.

Dan Heaton: That sounds really fun.

Rick Harper: It was.

Dan Heaton: I’m a little jealous, especially early on. I mean, to be able to do that and also probably too, it’s just reinforces that you’re working on something so cool that you get to enjoy it rather than just see the difficult part of it.,

Rick Harper: That’s true. I rode that by the way, when it was, oh, just near opening. I rode that ride in an interesting, it just kind of fell in my lap. The situation I rode it with John Hench, Ron Miller, and Edna Disney, Roy’s wife.

Dan Heaton: Wow.

Rick Harper: Yeah, she was like 83 or something at that time. And Ron is going, yeah, no, are you sure you want to ride? Her answer was, oh, this can’t be any worse than those Coney Island rides. So she made it through and we helped her out and out of the thing, and she had to get her sea legs back, but she was fine. She had a smile on her face.

Dan Heaton: That’s great. Well, you mentioned John Hench. I mean, he’s a masterful designer. I love his book. He wrote a book Designing Disney, but so many things he’s done for Imagineering, especially in Disney World. Could you talk a bit about what it was like to kind of work with him or interact with him?

Rick Harper: Yeah, he was just, of course, one of my childhood heroes and getting to know him was just really a fun time and an honor because he was so talented and he had this very dry sense of humor. And wit, I mean, he was an intellectual for sure, and he liked being perceived as that, and he earned his medal for that. And we became very close. I don’t know, I have my theories about why, but I think it was just one of those things where we connected really well and it was fun.

Oh gosh, there’s so many funny experiences with him. But I traveled with him quite a bit during some of the research trips involving Epcot. And we were, a handful of us would go to different companies and wanted to present basic ideas and kind of see where they’re at for, get a little bit of feedback and try to generate interest in sponsorship.

So there were a lot of concepts worked up and presentations made that we’d make, and sometimes it would be just for research. For example, one of the trips involved going to Johns Hopkins University where there’s a lot of very important medical research that goes on, and we spent several days interviewing some of these people that were on the forefront of the cutting edge discoveries and research that was being done at the time.

So there was one interest that is really burns a memory in my mind of John and I were sitting together there, and there were a couple of younger ones of us. It was mostly, by the way, it would’ve been, let’s see, Marty, Randy Bright was one of the younger ones. Let’s see. Claude was there, I believe, and X Atencio may have been a number of these people that had all this background at Disney.

So we’re all sitting there taking notes, and it got to be a little mind boggling, like being in a college class that’s over your head and the lectures go on and on and you’re just kind of going, oh my gosh, how much can I take? So John and I were scribbling notes down, but we started drawing caricatures of the people that were doing the presentation during the question answer session, while other people were asking questions. We started drawing portraits that as the hours went on, the portraits became more like caricatures and we would kind of tip our pads toward the other one to share it, and we’d each kind nod with kind of a, oh, yes, that’s an important note you made there and whatnot.

Well, pretty soon one of the guys that had been there for most of the meetings, a representative that was there, there were people coming in and out talking some talk for 30 minutes, some talk for an hour and a half, but this fellow had been there a while and he just suddenly blurts out, can I see your notes? And he’s talking to John and me. It is real clear. Both John and I look at each other and we kind of, oh, yeah, yeah. So we’re trying to page backwards to where we had only writing and the guy gets up and he goes, no, no, no, no, no, I’m talking about the drawings.

Oh my gosh, I thought I’d have a heart attack. John played it cool, which he was very good at doing, and Marty came to her rescue. The guy came over and he took the pad right out of one of our hands, and we’re just sitting there waiting for some kind of consequence to come down. And Marty said, well, you have to understand these are Imagineers. They have free flowing ideas, and sometimes it’s kind of in the zone. It’s kind of out of the boundaries. But that’s part of my job is I try to kind of corral ’em into the right thinking, and sometimes I have to use a whip. Well, that resulted in a nervous laugh on the part of everybody, and we went on and we were fine, and my heart started beating again. I’m happy to say.

Dan Heaton: Oh my gosh, that’s great. It reminds me of being in college when you’re not totally paying attention and you’re called on by the professor, but this is in a totally different setting.

Rick Harper: Yeah, that’s right. It’s kind of like you want to share that with the class. It’s like, oh, man.

Dan Heaton: No, I’m good. Thank you. Well, speaking of Marty Sklar, I mean, I’ve read his books, he’s done so many interviews, but I’d love to know beyond him cracking the whip a few times, what is your experience like with him working together with Marty when you were at Imagineering?

Rick Harper: Well, a total delight. I mean, he was so great to work with. He was reasonable. He was a very good manager of the zoo, you know what I mean? That was really his thing was he would kind of corral thinking, and he was very open. For example, when I wanted to go about the French film in a completely different way from other circle and films, he got on board pretty quickly and was extremely supportive through the whole project, but also he was personal.

And for example, when Ann and I had our first child, he sent this great letter that was kind of silly and kind of fun and just a way of saying, Hey, baby Harper, behave. Please. We’ve got a lot for your father to do here, so make life easy on him or something. It was something of that order. He would do things like that. He went out of his way to make a personal touch. Another example is when I applied for a loan for our first home for Ann and my first home, he offered and followed through with writing a letter to the loan officer because the issue was, I mean, being in the entertainment business on any level, at least at that point with the banks, was a risk. And because I was pretty young, it was a first home situation.

It actually was interesting because the loan officer, her husband was in the movie business and she understood, she said, these loans are kind of hard to get through. So I said, well, I could probably get some letters written that would demonstrate a secure future. She said, great, do it. Well, Marty was quick to do that and wrote a great letter to her, and that took care of the whole thing. So that’s typical of him. He even wrote a letter for me long after I’d left Disney and I was getting involved with another project. He even wrote a letter for me that was all this very, it was like a recommendation letter on Disney letterhead to the person that I was making the presentation to, so with another company entirely. So he would do things like that. He was quite something.

Dan Heaton: The amount of people that I think have similar experiences with him are, there’s so many. He just seems like an amazing person, and it’s great to hear that he was like that in person too. He was such a public face of Disney in a lot of ways, especially in the past 20 years or so, or after Walt passed. So to see that he was that way behind the scenes is awesome. So on a completely different note, I know that you mentioned when you worked on Spaceship Earth, you did some work with Gordon Cooper, the astronaut. I would love to hear if you have any stories of Gordon Cooper who was one of the Mercury astronauts and being involved with that.

Rick Harper: Yes. And he also flew a Gemini flight as well. Yeah, it was interesting. He was brought in to help. There were a couple of people brought in to really help Disney shift their image from Mickey Mouse cartoons. Most of the public thought of ’em that way. And of course, the wonderful animated films, Mickey Mouse Club, and Disneyland. He and Ray Bradbury were brought in to help be an appealing image to the corporate world. Having those two people who were so well known and associated with technology and the future and future thinking and all that kind of stuff, which was what Epcot was supposed to be all about, it helped kind of set the tone for Disney going in that direction.

It gave a validity, offered validity to that. And so both of them were very amusing people in different ways. Gordon just had, you could see, I mean, I remember the first meeting where I was in the room with him and I had done some concept work on Spaceship Earth and some other things, and it was in those years right after Space Mountain installation was done. When I got back, I was suddenly moved into design work instead of the model shop, and I was invited to all these meetings.

So when Gordon Cooper came in, oh, there must, I don’t know, there were maybe 10 of us in the room and we’re all just asking him questions about his experiences. We learned right then and there that he was very congenial, very easy to get along with, had a wild streak. For example, he had told us about how the space food was so terrible during the training periods. He smuggled a ham sandwich in his spacesuit and it really got him in trouble. It screwed up all the blood sugar recordings and all the other stuff they were doing on the flight.

He had some other rather earthy stories about the goings on and being in the Gemini flight for basically eight days. So he was a character traveling with him. So it was a lot of fun. There were three locations that we went to primarily with him that I recall. The Johnson Space Center. The Kennedy Space Center, is that right? There’s one in Texas and one in Florida, and I get mixed up who’s who I think.

Dan Heaton: You got it right. Yeah, Florida is Kennedy and Texas is Johnson.

Rick Harper: Oh, that’s right. Of course that adds up. So we went to those space centers as well as to the Smithsonian, which at the time had a display of both a Mercury capsule and the Gemini capsule. I’ll tell you when I saw those things and I just could not believe how small they were, I mean both of ’em, and I mean the Mercury one was small, but the Gemini one and fitting two people in there for eight days, Mercury was, I forget, it was what, maybe a 20-hour flight. I forget what it was, but the other one I know went nearly eight days.

Plus, when you think of the technology of the era and the risk level involved, it’s just totally amazing what this guy did. But meeting him, you’d never know. He was this hero that we all thought of him as. He was very easy to get along with. Of course he had an in to say the least in all of these places. So that was fun to see. We had free reign to see whatever we wanted, and of course saw some very interesting things related to the training and all of that kind of stuff.

Dan Heaton: I can imagine when you’re one of the original astronauts and you probably don’t get told no a lot when you’re going around those areas, I would think that has to be really fun. But it’s great to hear about him because I’m more familiar with him as Dennis Quaid and The Right Stuff or him on various fictional things, not the actual guy. So that’s really interesting. That’s a fascinating story. So another thing I wanted to know about is you referenced this right before we started, which I know nothing about, is you were involved with working on an idea for an Arab pavilion with Harper Goff. And I’m really curious about this because it’s not something we hear about very often.

Rick Harper: Yes. Harper was one of those people, I’ll start with him in general. He was one of those childhood idols of mine, largely because of his work on 20,000 Leagues. And I was fascinated by his stories about how they were filming some of those miniatures, the effect shots, which involved anamorphic lenses, which it’s amazing what this guy, he was so practical, this man, he could look at a problem and go about it both creatively and very practically.

A good example is on the World Showcase pavilions. At the time that he came in, the pavilion designs were all on the different structures, much like, like a World’s Fair would’ve been where they’re all totally different structures. And he came in and he took a look at the situation and said, you know what? We need to redesign the big picture here. And he came up with the kind of pie shaped, I’ll say, truncated pie shapes like the slim end of it, cut off all those pavilions, basically have that shape structurally.

That saved just mega bucks going about it that way. And then of course, the facades are all designed very differently, and so most guests are not aware that there is this common structural design to each one of them or to all of them. So he saved gobs and gobs of money with that. So I got to know him a bit on that. And also just connecting with him about his, I loved hearing his stories about the films he’d worked on. He had done a film for Stanley Kubrick where he told some really interesting stories about how he went about things. He’s very good at saving people money in these projects, and not only doing that, but simultaneously coming up with something better visually.

And he was a very open human being, a really sensitive individual. I have a vivid memory of him sharing with me at a point where his wife had gotten very ill, him just, we were in his office together and he just started talking about her and how much he loved her, and he just broke down and a sobbing, and it was a very emotional time, but this is something most people have a draw a line, a social line in that kind of thing. But he was just real right from the get-go. So that was something about him that was quite amazing. But he also, I was floored when he gave me a model of the Nautilus that he had had made.

My understanding was that he’d gotten the old plans out, and he worked with Tom Sherman, I think was his name. Tom Sherman was in the model shop, and he really had an obsession about the whole Captain Nemo thing, the whole 20,000 leagues. He had an apartment, in fact, that he had converted by putting a ship’s ladder between the top and bottom floors, and the whole place looked like the inside of a Nautilus, it was. Anyway, so he was something. Anyway, he and Tom Sherman worked on getting these models made, and then Harper gave them to various people, and I was just floored when he gave me one.

I still have it and I love it completely. So on the Arab Pavilion in World Showcase, there was originally going to be a Middle East pavilion, then it was going to be an Arab pavilion, then it was going to be a United Emirates Pavilion, and it eventually morphed into the Moroccan. So that’s kind how things would go on these projects. But in the stage where it was going to be the Arab Pavilion, I was assigned as the designer on it and on the ride itself. So it was like all of the World Showcase pavilions.

We wanted to romanticize the country. Well, much the way the French film does. We didn’t want to show the industry side. We wanted to show the appealing part of what it would be like to be there and experience the place. So I worked with a writer named Gary Goddard at the time, who was also brought on as a writer, and we worked together on coming up with a magic carpet ride concept.

Then I did a bunch of illustrations for that, also working out the ride pathway and that kind of thing. And I believe at one point I sought Claude’s advice on some of that. But the presentation part, we went to Washington DC where there was a fellow named Lang Washburn who had experience in the diplomatic world and whatnot, and Disney had hired him to set up an office in Washington DC and we did a bunch of presentations to various Arab ambassadors that came in.

Generally things went pretty well, but as usual, the issue of, well, gee, we want to show our industry we want to. And all of the pavilions went through that. So there was always this awkward time at trying to find a meeting place between those two needs. So we worked those things out. And the United Emirates in particular, they stepped forward and they were very interested in it.

So we set up a presentation in their embassy, which was just outside of DC and Maryland, and it was a fantastic environment to walk into. It looked like the Alhambra Palace. It was incredible inside with all this inlaid mirror and all this amazing stuff and quite an experience. And we set up in there, Jim Elliott was with us with this big model of Epcot, and there were about 25 or 30 ambassadors showed up and did this presentation.

The presentation involved a movie that had been made that I had not seen the most recent version of it. And so in running it, well, lemme back up. Alright, I thought I better view this thing just so I know what’s there. So while Jim Elliott is setting things up and a couple others, I view the film and here comes a court of flags scene and it has a panoramic going across the court of flags. And it’s just an illustration that Colin Campbell had done. And among the flags as France, Germany, it’s all these Europeans, the American flag, dah, dah, dah.

Here comes the Israeli flag and the ambassador went berserk. He said, this is, you’ve defiled my home. Get out of here basically is what he said. I’m calling it all off. And this is when 40 minutes later everybody’s supposed to show up. So he went storming down the hall, he was really, really upset. And Washburn goes running after him and somehow managed to patch things up and they come back together. And so I said to him, he said, we can go ahead with the presentation. I said, well, what about the movie? Is that going to be an issue? And he said, I’ll explain things if I have to.

He said, well just go ahead with it. So Lang earned his money in that discussion, whatever he did. Well in the meantime, while they were back there and after the initial blowup of this guy, I call Orlando Ferrante, I said, hey, have you seen the latest version of this? There’s this shot. And I explained to him what had happened and he said, oh Rick, you got to just explain to these guys this whole World Showcase thing is a brotherly love thing.

I said, well, Orlando, I’ll have to tell you the whole story when I get back, but thanks for your advice. We’ll see how things go. Anyway, things went well ultimately, and we got some strong interest from the United Arab Emirates, and that particular guy asked me at the end, it was all this discussion, we’re all standing around and yacking, and this guy comes up to the model, I was near the model. There was a specific model of that magic carpet ride and the entry court to the whole pavilion and all that stuff.

So he is looking at, he said, tell me what would this cost? And I’m thinking, I just answered the standard. We’re putting that together and give me your contact and we’ll let you know kind of thing. And he said, no, no, really, you must have some idea or you wouldn’t be here. And I said, well, just off the top of my head, Space Mountain was about 30 million or something like that. I think it’s probably in that zone. It’s probably about the same thing.

Well, oh my gosh. Then I got this horrible feeling afterwards like, oh man, I’m going to be fired for sure. This is a really stupid thing I did. And of course Marty just hit the ceiling when I got back. I confessed it to him when I got back and he went, oh, don’t ever, you have no idea what a mess you’ve made and that kind of thing. And so, golly, I can’t think of the guy’s name that headed up the budget department. He was actually kind of amused. And he said, well, yeah, I can pull something together.

I forget how many weeks he worked on it. He came up with a range, which actually I had told the guy, I had told the ambassador, I’d said, well, somewhere maybe between 25, 30 million, something like that. I mean, don’t quote me. And of course, anyway, so back to WED later on, the guy works on the budget and he came up with the exact same thing that I told the guy. I mean, working the numbers, it was one of the few times Marty really got angry with me. So I needled him about it when this came out. I said, hey Marty, I could save you guys a ton of money. Just let me know when you need something off the top of my head.

Dan Heaton: That’s really funny. Yeah, I mean you could be give some really broad range, but I’m glad it didn’t end up being that big of a deal because that would not be good.

Rick Harper: Man. No kidding.

Dan Heaton: Alright, well, I wanted to ask you about a couple more people that you worked with. One is Ward Kimball, who I know just was involved in so many interesting things at Disney, and I’d love to know what your experience was like with Ward.

Rick Harper: Well, he certainly earned his reputation as a wacky fun person, that’s for sure. My initial exposure to him was actually doing a film with him, and there was a fellow at WED that had contact information with a magazine that’s specialized in model railroading. And I was doing all these outside film projects. This is in the early to mid ‘70s. I was doing all these outside film projects. So this fellow, his name was Mike O’Connell, he learned about my film stuff and he said, Hey, I’ve got this magazine that I think I can talk ’em into doing a movie about model railroads.

They’re trying to expand the hobby into a younger audience. So I went, heck yeah, that’d be fun. So one of the first things we did was we got Ward Kimball involved, and he was involved in two ways. He kind of introduces the film in the beginning that we shot in a kind of little train telegraph station room that he had on his property there. It was out in Atherton area if I remember right. So he hosted that and he was a little nervous on screen, but he came through and it was a lot of fun working with him to do that. But also he had these full-size train engines.

He had a couple of, and a couple of box cars and things like this that were in this huge warehouse that the tracks led into and he could pull ’em out. So we wound up designing and doing a kind of a Busby Berkeley musical sequence with dancing girls as part of that film. He was very much involved with that too. So that was my initial getting to know him. But as the seventies carried along that film was I think in ‘73 we did that. And then in the months that followed, he was coming into now and then to work on a few things, and I got to know him further when we were kind of sharing an office space, which was actually really a conference room that was right off of Randy Bright’s office right next to it.

Randy used it for meetings and that whole kind area would use it for meetings. But Ward and I were in there working on two different things. So we started just having some fun things going on. For example, we began a series of tests on which type of cookie had the most grease, the cookies that were offered in the cafeteria there at WED. And by pinning, we’d pin part of the cookie on a sheet of paper on the storyboard wall.

Then we’d let these things sit for days and weeks and see how much grease would spread out from the cookie, and then we’d mark it what the dates were. It was like marking the rings on a sod Redwood tree where you’re marking the years and what the history was at that point in time. We were marking it that way. So that was kind of a silly thing going on in the room. He also gave me a model sheet, an updated Mickey Mouse model sheet, which is absolutely hilarious, where he updates different types of Mickey’s that might be utilized in future Disney films, an old Mickey, a hippie, Mickey, these different things.

There were about eight of ’em, really very silly. So he was a fun guy. And I also visited him a couple of times in his home out there. He had not only train collections, I mean an unbelievable collection of toy terrains from different era. So he had a whole different warehouse out there devoted to that. And part of that, he was starting to collect. Now this would’ve been, oh golly, this would’ve been maybe right around the ‘80s, somewhere in the early ‘80s he started, he was starting to collect the Japanese toy robots. He had an incredible collection of these things. This was before, I mean since then, those things are like crazy at auctions, crazy expensive.

Somehow he managed to get on the front end of that wave of collecting as well. So he was multifaceted. We also had a lot of discussions about art, which that it goes for every single Imagineer I worked with and knew. I’d always get into discussions about art because I’m always interested in who the influences are, and I have just a lot of interest in various artistic styles and approaches. We discovered that we both were crazy about this artist named Ronald Searle. And if you look him up on the Internet, you’ll discover some really wacky drawings. Ward was very influenced by this man. And in fact, even Walt invited him to the studio because there were a few animators that had took quite an interest in his work. He is out there wacky, and you can get a feel by seeing some of Ronald Searle’s work.

You can get a feel for the influence it had on award in films like Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom, and some of those kind of groundbreaking different approaches that were taken by Ward. You can also get an idea about the Mad Hatter scene in Alice of Wonderland certainly appears to be influenced by Ronald Searl as well. And we talked about even artists. I was a big fan of Mad Magazine artists that during the sixties in particular, early to mid to late sixties, there were some incredible artists for that magazine. And we discovered that we both love many of those artists. And he developed a later interest in Norman Rockwell. You would not expect that from a wacky Ward Kimball, but he developed a real admiration for the guy. And it was because he had finally seen some originals.

The originals are mind blowing. They’re very free brushwork and beautiful layered coloring. I mean, when these large paintings that Rockwell did for the Post when they were reduced in size for the magazine cover, you lost all of that. So Ward, that was a great awakening for Ward to make that discovery. And so he was an interesting guy. He had many facets. And of course, the Firehouse Five. There’s another aspect to him, and I had not realized until I talked to him about it that later on, this was in the later eighties. I didn’t realize that Harper Goff had been a member of that. He was part of the Firehouse Five plus Two.

Dan Heaton: I was thinking, I’m like, we we’re covering multiple people from the Firehouse Five here. So when we talked about Harper. So yeah, we’re just on top of it now. There’s so many great stories, and I love hearing about people like Word Kimball that had so many interests and were involved for so long. So I want to make sure we get a chance to talk a bit more about Impressions de France. But I think the last person I want to ask you about kind of fits with that, which is Don Iwerks who I know had so many important contributions just to innovations with film and how it was done. So I’d love to hear about you working with Don and then possibly something with Impressions de France too for him.

Rick Harper: Well, he was, oh man, he descended from the sky at the right time because in getting the concept sold of doing the French film differently from other CircleVision films, I really wanted to break the mold on some of the entrenched ways of doing CircleVision technically. And being able to tilt the system was in my mind, and I have a pretty good head for engineering, but I’m not Don Iwerks anyway, I kept thinking, man, this is a 550-pound camera system.

You try to put that on a gearhead, it’s going to be top heavy, and how on earth are you ever going to be able to do that? And so when I asked Don, I said, I really want to do some tilt up, tilt down. I want to be able to tilt the cameras anyway. He instantly said, well, I have to double check where the center gravity axis would be on that, but I think we might get lucky and just be able to build a cradle that it would work. I’m thinking, oh my gosh. And well, the axis, won’t that have to run right through the middle of the camera, go, no, no, no. You build around that. And basically he built this thing, and I mean he invented it instantly. Then it was built pretty quickly after that.

That was, if you can picture a baby cradle and that the axis invisibly goes through the center of gravity, but on the outside of where the actual baby seat is are two axis that become a cradle back and forth. It’s a little bit like a kid on a swing, doesn’t have an axis running through them. So anyway, he built that and it worked incredibly.

I could tilt this thing with complete ease during a shot, and it was an amazing device. We wound up using that on many locations and also would use it periodically for just a dolly shot or on the camera card just to either easily position the camera or to actually do a slight tilt during that, or in a case of the rare grab shots that we did, it would be helpful in just setting it up quickly. By the way, we did do grab shots on that film.

Dan Heaton: The way that the feeling of movement and just the way that film seems, I mean, you can tell that there were some inventive devices used because a lot of films, even from that time are very static. And the way that you’re on helicopters and we’re flying by the water and we’re riding cars and stuff. I mean, I watch that and I constantly am thinking, how was this done? Because we talked about it a bit the last time with the Eiffel Tower scene, but there are so many moments where I think, wait, they had a big camera. I don’t understand. So you could tell there’s some innovation there for sure.

Rick Harper: Well, he came to the rescue again on the whole helicopter thing. I mean, that was the other big breakthrough I was hoping to do, and believe me mean, the thing about Don is nothing phases him. He just goes, he thinks about it and he just forges the way. I don’t remember one honestly, in those years, I just don’t remember anything phasing him. And things got really difficult on developing that helicopter mount over a period of months.

It was full of challenges. I mean, the problems of how are you going to land the helicopter? You got this big thing hanging underneath. It had to develop tables that it could land on, and the camera would have to be hovered down slowly by our magnificent pilot, Mark Wolf, very carefully down there. And tables only allowed for about maybe eight inches on either side of that camera system.

But we knew we had to have a great pilot, and that counted. Also he came up with the best vibration detection system that we could do at the time. That was a great help because I had to be very aware of if these look like a little echocardiogram readout on paper, by the way, no digital imaging here. So I had to be very aware of those while we were filming.

If that chart ever got beyond a certain point that we had established would be too much vibration. So yeah, so allowing for that kind of filming benefited the movie incredibly so I was very, very, I am so grateful to Don for his contribution to that movie, which opened the way. We were the first of the movies to go into production. It opened the doors for the other CircleVision films and the other large format films to utilize the helicopter mounts.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it makes a big difference.

Rick Harper: Incredible, yeah.

Dan Heaton: You’re not doing, I mean, CircleVision, I think you described last time a lot of it was early on you were kind of just putting things on cars and driving them where now you can put it up in the air and float around. It’s a totally different, but you mentioned vibrations too. I think about scenes like the car racing scene at Cannes, or even the market scene and those things where you’re like, we’re moving along. Was that a real challenge for either of those to really keep it from getting too unsteady, I guess, in a way?

Rick Harper: Always. And the wonderful French crew that we had, oh, just fantastic people headed up by a man named Rene Strasser. And by the way, there were four total of four Strassers, no five, excuse me, that were involved with the crew one way or another. So they were a family that had done a lot of American productions over there, like charade and some other films like that. But none of ’em really spoke English. So I always had my drawing pad with me.

I only knew, I don’t know, very little French and probably pronounced it terribly, but drawing seemed to get me by. But they were really behind this film. They were so great at looking out for those important things in the market scene. It was a pretty complicated setup because I asked Rene if he could build, this was attached to the dolly itself, which wasn’t all that large around the camera.

He built a platform just out of sight of the cameras on the front so that we could set all those flowers around the front of the camera, and it added a lot of color and interest, and it also gave some interaction between the two. There’s a woman and a young lady that are kind of pulling the cart and opening it a shot, and then they stop the cart and they pick up some of the flowers and they delivered ’em to various people around at the different areas.

The big thing that was always a challenge was those dividers between the screens that I didn’t want somebody’s face winding up there. I didn’t want some sign or some written thing to suddenly spell a different word or as you know what I mean? I had to be really careful in setting up these shots. And so that scene basically, I mean, we hired the whole village.

We found a great little village in Normandy called Baron, and we just basically hired the village to set up their usual market, and everybody was directed very specifically in that we were dodging cloudy weather during the shooting day, and it drove us all nuts. So we had to keep repositioning and starting all over and trying to anticipate when the sun would break through and if it would last long enough. We had very little breakthroughs of sunlight. So we had to do quite a number of takes to get that shot. But it finally worked out.

Dan Heaton: The choreography of that and just the setup, even for none of the shots are super long. But for a shot like that, it’s a little mind boggling to me that you were able to pull that together. There’s a lot of, like you mentioned, so many different elements. Plus it has to look good and work. I am really impressed by it.

Rick Harper: Well, thank you. One of the tricky things was during shooting, there was no way to see, actually see what was on those screens, and there was no way to, therefore there was no way to actually see where those dividers, if somebody was going to stop on the wrong spot. So what I had to do was Mark, I’d have visual markers out within the field. I go, okay, well that particular potted plant, I’m going to position that on one spot.

So I know that just to the left of it is where the divider’s going to be. I had to, and then a moving shot, I got very complicated, so I had to get behind the camera and try to make my best judgment about, are we having a problem with that or are we not on the moving shots, like the balloon liftoff, oh heavens, and the market scene and that kind of thing.

Dan Heaton: So for Impressions de France, did you have any type of video assist or any way you could at least have some guidance when you were shooting some of the more complicated shots?

Rick Harper: So on that black-and-white video assist, it was a little screen that was, oh, maybe three inches by four inches, and I could mark on that with a grease pencil, an approximation of the front camera. I could see that while we were filming and the wires ran from, and the camera was placed on top of the, or above the CircleVision camera. So it was an approximation, but it was helpful in at least trying to get in the front camera, trying to avoid those divides when we’re flying along there.

I wanted to have this certain, for example, the Bell Tower, when we fly up to it, I want to be sure that was in the center screen. So it was helpful, but viewing that with one eyeball and the other eyeball, double checking the vibration detector constantly, and then giving constant verbal direction to mark, we weren’t just flying randomly. There were very specific directions as to, okay, we want to keep this, alright, now we want to veer to the right 30 degrees. Okay, now tilt up as you fly over this, but keep that center frame on its own. Yep. Alright, now we’re, we’re going to go left a little bit.

It was a constant thing and Mark was so great about being able to do virtually anything with that helicopter. An example is you may recall the shot of the skiers in the Alps there. We’re following them along, and we are at times, we’re only about the camera’s only maybe eight feet off the ground and they’re initially in the center screen, but as we move up closer to them and they’re skiing along there on that side of that slope, I asked Mark to fly a little bit sideways at about a 45-degree angle, still flying forward in the direction that the skiers are going, but I wanted to now see them in profile as we’re going by them.

While he’s doing this, he’s having to fly underneath two ski lift cables, which by the way, we only got one chance at this for that reason, and then correct the flight more to flying straight as we continue on. And these very specific, oh, and he also had to tilt during part of it to keep them in frame. So he was really something and having a video assist definitely helped in those situations.

Dan Heaton: So summarizing on Impressions de France, one thing that interests me too, because I think it holds up so well, is technology, like we’ve talked about, has changed a lot over the years. So I’d love to know for you, just what are some ways that it’s changed a lot that would’ve made shooting a lot different for you if you had that technology?

Rick Harper: Well, the Mitchell cameras, which were used on that, they did way back to even to Edison technology and the lenses date back to probably the 1940s and this kind of thing, and there’s no viewfinder when you’re shooting, you can see all five cameras. So that was tremendously limiting. Then of course, the weight, the sheer weight of it. Well, we all know that in the digital realm, you can get very high resolution with these extremely lightweight systems and you can see it immediately and just right there and you’re not going through chemical soup.

That can ruin the color timing of the film and the kinds of things that were issues with, especially shooting with a fine camera system. So you’re not dealing with sprocketed film and you’re not dealing with having to go through negatives and then inter positives, and then your final print, which creates a contrast issues along the way with film technology. So the digital realm has opened up so much and also the lightweight nature of it. Secondly, we were using for lighting, using incandescent lighting.

When I, oh, by the way, I would bring along my own lighting kits that I’d purchased and collected over the years, and I had several cases of lighting equipment and Joe Nash would pack this stuff up along with everything else. When we were shooting American Journeys or even the Magic Carpet film overseas, and even the French film, I had my own lighting equipment with me in addition to what we would use that was available locally sometimes, which was extremely iffy.

Anyway, so with LED lighting, you have this amazing, again, lightweight, it’s cool, so you’re not dealing with all the heavy containers that the lighting has to be on. So again, it reduces weight. Oh, the other thing about digital, you can shoot in such low light, you can use a couple flashlights and ambient light coming through a window and make something very beautiful out of it. Whereas before you had to build that up with a lot of light. Oh, that was the other thing about using film. You’re dealing with film speeds that were very limiting.

Now I’m not talking about the speed that the film runs through the camera, but what was known as the how light sensitive it was. And often I was using a SA 25, which was the slowest film speed, because I wanted to get the warmth out of it. It was their code of color Codex best film in terms of low contrast and achieving warmth in a scene. So I would use that film. Oh, that also would result in my having to sometimes under crank the film, which meant, for example, the tilt down shot inside in that church, I had to shoot that at six frames per second, not the standard 24 frames per second.

I had to shoot it at six frames per second in order to get enough light onto the film through the lens. The lens was a, oh, I think it was a 3.5 F stop. So that was kind of limiting in itself too. So today you could do that without lighting it at all. It would look great, these breakthrough, oh, and of course the drones, that’s a huge one right there. You could get so many amazing things with the drones that wouldn’t involve the daring do that we had to go through a few times.

Dan Heaton: It’s almost too easy now. I think you had to go through a lot, but I think the results are spectacular. I mean, they still stand up so well, and I’m glad that people still get to see it in some capacity. It’s great. Well, I want to ask you about something totally different, Rick, which is the speed tunnel at Disneyland. We talked a little bit about it last time. I love speed tunnels and how they can simulate motion. But I know you had kind of an interesting experience while shooting in the Everglades, unfortunately, and I would love to hear a little bit about that.

Rick Harper: Well, yes, in general shooting, that film always involved some riskiness because we were having vehicles or boats headed straight toward us and then varying off at the last minute, and this is while we’re moving on a camera car or on a boat toward those vehicles that are coming toward us. So there was very much some riskiness involved with that. In the Everglades it got even trickier because these boats, the Everglades boats, as you are probably aware, they involve these huge airplane propellers on the back of them.

The boats themselves are kind of like skiffs and flat boats. And with these big propellers on ’em, when those propellers are fired up, these things go charging forth, not with a lot of control to them. So we had, I don’t know, I forget maybe six boats, six or eight boats, and we had a camera boat, which was also one of those everglade boats I knew on these shots. I had to rehearse scenes very carefully, very slowly at first. So people got an idea of the dangers and critical nature of closing speeds. That is the speed that the combined speed of them coming toward us and us going toward them and then veering at the last minute. It’s a hard thing to judge.

Even for stunt drivers, and we weren’t working with stunt drivers, we were working with drunk drivers because they were a happy bunch. And during, in between our different rehearsals, they’d all have another round of beer and I was getting pretty concerned about that along the way. So anyway, we get set and we’re doing a take and things are looking pretty good. Then I can see that along about maybe the fourth boat was not judging that speed correctly. Art Cruickshank was to my right, the camera was kind of between us in front of us a little bit, we’re in the front of the boat.

By the way, on that project, art was the cinematographer and Joe Nash was with us too on that as a camera technician. Anyway, so Art and I are in the front and then behind us there’s Joe, the driver of the boat and a local contact. So this thing is not, and Art, and I can see right away, oh my gosh, this thing is going to hit us. And this is all in a split second. Art turns and leaps tries to leap over the backseat. He kind of gets mostly over it.

Same with me, we’re doing the same thing, but the propeller of that boat, he’s sliding, trying to veer. So he kind of slides into us at a 45-degree angle and therefore the propeller lodges in the front of the boat misses the camera, lodges in the front of the boat and snaps into a zillion pieces and all the shrapnel is going everywhere. Art, I was extremely concerned about Art and he was fine. He wasn’t hit, but I was hit in the rear end and oh my gosh, it felt like, I mean, it was extremely painful. I thought, what happened here? Anyway, it turned out to be a very large bruise.

It took months to go away, but that was of course later on learning all of that. But so we returned to the dock. The guy is all upset whose boat hit us and he’s extremely upset. So I talked, I got our production manager, Bill Schneider. I just said, whatever this guy wants, pay it. And so he handled that very well and next thing you know, all the boat owners are having another round of beer.

Meanwhile I’m thinking, oh boy, I got to call, got to call Orlando. See, Orlando was on that project. Also my contact person, I would kind of report to him every day what was going on, where we’re going, what kind of successor we had and all of that. And always good natured. He was always fun to talk to. But again, so I call him and I say, Orlando, he’s going, well, how’d it go? I said, well, no one was hurt. He goes, oh my God, what did you do? So I explained it to him and he eventually calmed down what I’m thinking. This is one of those yet another situation where I’m thinking I’m probably going to be fired.

But that didn’t materialize fortunately, but I was worried because in the ER, somebody called an ambulance and I was whisked away, which I didn’t feel is necessary. But I was brought over to a hospital and while they stick me in a little room there, I’m watching the news and here we are on the news. Some guy had shown up that had shot a little video report of the whole incident, talking mostly about it. Of course he didn’t have a camera, he wasn’t there when that actually happened. And so I’m now worried, oh my gosh, they’re going to see this in California somehow or other this because it’s Disney and it’s all, but anyway, it all turned out okay.

Dan Heaton: Wow. Between this and Impressions de France, I think the life of an Imagineer and especially a film director is much more dangerous than I thought, Rick.

Rick Harper: Well, when you’re crazy, yes.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I think it’s part of the job though. The job description. You got to be a little crazy to do so many good things.

Rick Harper: I think you’re right.

Dan Heaton: Okay. I wanted to ask you briefly, you sent me some art of a Captain Nemo restaurant, which to me, I feel like that looks like something that could totally open today, and I’d love to know a little bit about that concept and how that came together.

Rick Harper: Well, that was something I did for Tony Baxter. We were both in our both big fans of 20,000 Leagues. And so I thought, gosh, it’d be so cool to do a restaurant based on that. And I dunno, I just got this idea and I first did a little sketch and I thought I’m going to do a full blown thing here. So that was a fun illustration to do. It was really fun and Tony just loved it and he would try to sell that thing. Over the years, it was so funny because I did that right around, I’m thinking it was probably right around 1975. I did that, maybe ‘76. I did that illustration.

And anyway, as the years went on, this illustration would kind of circulate and I’d walk by this conference room or that conference room and it was in there. It was in there, and then it was back in Tony’s office and it was constantly popping up and I’d check in with Tony and go, is this ever going to happen? Or what? He said, man, I’m working on it. I keep trying to get this thing sold. And amazingly, I think some version of it, very watered down version of it occurred, but I’m not even sure of that. I think there was something in one of the parks that some watered down version, but no pun intended. But anyway, that’s the case with that.

Dan Heaton: I feel like it could have worked in maybe, I know Tony had a lot of ideas for a Discovery Bay.

Rick Harper: Yes, that is what I did it for initially was I had done a few little sketch ideas for Discovery Bay and we talked about it. Captain Nemo restaurant, oh man, I want to really do a real illustration for this. That is how it came about.

Dan Heaton: Interesting. Well, I’m just going to ask one more thing. I know we talked about so many people you worked with. One person we haven’t mentioned that I know you worked with was X Atencio. Pirates, Haunted Mansion, so many great things he was involved with. I’d love to hear a little bit about him and what you did when you worked with him.

Rick Harper: Well, another dream come true, really to be right next to him in an office there for a few years. He was quick to give good advice when I asked it. And he was friendly, had a great sense of humor, but every once in a while he could zinging you and it was a real shock. There was a thing where during Space Mountain development, and I think this was when I came, no, it would’ve been before I went to Florida, actually X had written some dialogue for some kind of chatter between different commanders on whatever the Space Mountain crew was supposedly, and some of that stuff is still there.

But anyway, he got a group of people together and I was one of them. I was asked a lot to do narration and things like that. And I’d always tell people, my stage fright is ridiculous. I’m not a good narrator. It would usually prove to be true. This situation involved about six of us reading from a script that X had done, commander X 1242, we need to eject such and such hatch, and it was all this kind of jargon and we get a little ways into it and everybody just needs to be doing fine. I think I’m doing fine. And X looks at me and says, Rick, you’re terrible at this.

I said, well, X, I warned you. He goes, oh boy. So we kept going, and much to my surprise, anytime I went on Space Mountain, no matter which park it was in, I always heard myself in there. Ann would point it out to me as well. So I guess he decided differently at that point. He was one to be very generous with his talent in writing. For example, when Ann and I got married, he made this beautiful card that a bunch of the imagineers signed. I mean he was really very generous with his time on that kind of thing. And I have several pieces of artwork and cards and original art and that he put in some of my books that I asked him to sign, like The Art of Walt Disney book. He did a couple full-blown illustrations in there that are really wonderful.

Dan Heaton: That’s great to hear because I don’t know, I mean a lot of people, the legendary Imagineers, you hear a lot about what they did on the biggest attractions, but not some of the other stories. So these have been great stories, Rick. I love hearing them.

Rick Harper: Thank you.

Dan Heaton: Alright, well this has been awesome. I feel like I could go scene by scene on Impressions de France with you because I love that film so much, but you’ve given so many, it’s such great background. I’ve loved getting to talk with you again, and thanks so much for being on the podcast.

Rick Harper: Well, thank you again for the opportunity. It’s a real pleasure talking with you.

Leave a Reply