Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

We all take the artistry of theme park attractions for granted, especially ones with less obvious work. We marvel at animatronics on Pirates of the Caribbean or thrills in Space Mountain because the work is out in front. That success is more subtle with the filmed attractions, particularly in EPCOT. A perfect example is Impressions de France, an opening day attraction in 1982. It’s more than just a travelogue and creates a dream-like feeling of drifting through a French countryside. There is a reason the film hasn’t received an update while playing constantly for more than 35 years.

My guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast is Rick Harper, who directed Impressions de France. He also worked in the model shop at WED during the 1970s and shot the Circle-Vision film American Journeys. During this extensive look at his career, Harper and I discuss the following topics:

- How did Harper get started at Disney and what interested him about working there?

- Who were the Imagineering legends that mentored Harper in the model shop?

- What excited him about directing a movie for the French pavilion?

- How were the music selections chosen and used while shooting the film?

- What were the biggest challenges with using the massive camera?

- How was the editing handled while shooting in the pre-digital era?

- What was it like to shoot the climactic scene with the camera moving up the Eiffel Tower?

I loved the chance to speak with Harper and learn so much about producing Impressions de France. Beyond that film, his story of joining WED is fascinating on its own and includes much more than just one project. This is one of my favorite conversations thus far, which says a lot.

Show Notes: Rick Harper

Watch Impressions de France in this HD version from Martin’s Videos.

Learn about the Beauty and the Beast sing-along coming to Epcot’s France pavilion.

Related Articles and Podcasts

Impressions de France: An Appreciation (Blog)

Tomorrow Society Podcast, Episode 33 – Composer Bruce Broughton

Tomorrow Society Podcast, Episode 43 – Steve Alcorn on Building EPCOT Center

Photos included in this blog were used with the permission of Rick Harper.

Transcript

Dan Heaton Hey there. Today’s podcast is all about Impressions de France with Director Rick Harper. You’re listening to the Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks so much for joining me here on Episode 61 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. We’ve seen so many changes at Epcot over the years, and there’s not that much left from the early days of the park. And that makes me appreciate even more the attractions that either were there at the start or at least have a similar feel. You think about attractions like Living with the Land from the ‘90s or Spaceship Earth, which has changed but is similar, or the American Adventure, which has only had very small updates.

And I think the attraction that most embodies that feeling that is still playing is Impressions de France, which was an opening day attraction in 1982 and has been playing consistently for more than 35 years, which is crazy. And I think one of the reasons it’s done so well is that it doesn’t feel dated. It feels like a dream. You’re going past these timeless places that are from various eras, but all feel classic. You’re experiencing life in France and there was real style and elegance to the creation of this film. This made me so excited to have the chance to speak with Rick Harper, who directed Impressions de France.

What I learned after speaking with him is that his career is so much more than that film. He directed American Journeys, the Circle Vision Film. He worked in the model shop with so many legendary Imagineers at Disney. Also, he directed commercials and has filmed so many things over the years. As I spoke to Rick while we were preparing to do the podcast, he also sent me a lot of interesting photos. Several are in the blog that accompanies this podcast and seeing the behind the scenes photos of how they put Impressions de France together made me appreciate it even more.

And that went through the roof after talking with Rick and learning how everything came together. So I can’t wait for you to hear this conversation, which is up there definitely with my favorites I’ve done on the podcast. But let’s get to the main event. Here is Rick Harper.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Well, my guest today is a filmmaker who directed the classic Epcot attraction Impressions de France and the Circle Vision 360 film American Journeys. He also worked in the model shop at Disney during the 1970s. It is Rick Harper. Rick, thank you so much for talking with me on the podcast.

Rick Harper: Well, thank you for talking with me.

Dan Heaton Oh, no problem. So before we dive into the films, let’s talk a bit about your background. How did you eventually get interested and start working for Disney at WED?

Rick Harper: Well, as far as getting interested, I was born in a magical year in 1950 when the culture for children was full of Disney. And so honestly, by the time I was six or seven, I was telling my parents I wanted to be a Disney artist. A few years later, I told them I wanted to be a Disney animator. And a few years later, after that, I told them I wanted to work at WED when I learned what that was. So the interest was very early.

Now, as far as getting hired there during early in high school, I started building architectural models out of mostly out of paper using some of their materials. But then they got more sophisticated and I began taking pictures of them with very theatrical lighting and whatnot. So I was kind of building a portfolio in the back of my mind. Eventually, I actually sent one of these models to Roy Disney, Walt’s brother, as a gift of appreciation for the wonderful creations that he and Walt brought to this world.

He sent a remarkable letter back that meant so much to me, and it gave me the confidence to to keep pushing to get an interview at WED. And that eventually happened. I was able to present these models to an amazing group of people who are have became Disney legends. John Hench called Marc Davis, all these people like Herb Ryman and Yale Gracey. These are all people that I was able to present to work to. So eventually that led to me being hired in the model shop and working directly under Claude Coats.

Dan Heaton You arrived at a time too, where it was interesting where, like you said, a lot of that group was still there. It was, you know, coming after Walt, but still a lot of the old guard. You mentioned working under Claude Coats when you got to that model shop. Working with Claude and some of the other group, what was it like being in that model shop at that time?

Rick Harper: Well, it was heaven for me because I knew since I was about 10 or 12 years old, I began realizing who these people were. I had, you know, Mickey Mouse Club books and things like this where a lot of these people had done illustrations like Herb Ryman or Frank Armitage, Marc Davis, Claude Coates had done a few illustrations in these, and these were Ken Anderson, Ward Kimball. I mean, all these magic names and I admired their art greatly.

Incidentally, I was drawing. My earliest memories are drawing and I’ve always drawn excessively and a bit obsessively. And so the designs and drawings fascinated me. So by the time I was actually interviewed and working there, I was very familiar with who these people were, and I was in great admiration of their work. It turned out to also be wonderful people, just wonderful human beings, and Claude certainly meets that description. He was fantastic.

I owe a bit of debt to Tony Baxter, whom I also met immediately there because he was still doing his work in the model shop there as well, although he was, he had moved into design work, but like Claude, he preferred working in the model shop area. You know, Claude had given Tony a lot of chances and Tony performed so spectacularly. I think it’s what gave in many ways gave Claude the idea to to push me along toward design and then eventually to filmmaking.

Dan Heaton Well, that’s so interesting that you were there around that time because, you know, Tony now is considered, he’s like one of the Imagineering legends, but at the time was just a fairly young guy, just kind of trying to make his way.

Rick Harper: Yes. And I mean, we hit it off. Tony and I hit it off immediately because we were in the younger generation and we both grew up in complete awe of these people and of Disney. So Tony became really a confidant because there were always political issues and things, you know, within a company. But also in terms of he was always terrific with guidance and design ideas as well. So he would look to me periodically for illustrations or storyboard ideas and we would compare notes. He’s still a great friend and that man is a genius, I can tell you that.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I’ve heard he’s done some interviews on some other shows. There’s one called The Season Pass where he did multi-part interviews that are fascinating. I mean, the guy, what he knows is just incredible, but I know you worked on models for the seventies. We had the start of Walt Disney World and such. What were some attractions that you were involved with in terms of the model shop?

Rick Harper: Well, early on, the very first assignment I was given was they were building; they wanted to clear an area in Frontierland and Disneyland for some arcades, but they wanted them completely redesigned and Disney-ized. But these were old arcades that they’d gotten out of, you know, bars and saloons. And somebody had torn out all the stuff in there except the mechanism, which, by the way, it’s interesting working on those because. Well, let me back up a second. I was asked to basically I mean, right off the bat, I was asked to take on a design challenge, was to take a theme that Tim Cook, I think was a guy that was kind of supervising what I was doing.

Initially, there were ideas for, well, this should be, you know, maybe this will be about such and such and include these characters. So it was then up to me to just kind of convert all these weird mechanisms which were stripped back to raw metal and mirrors and chain drives and things. And by the way, they’re all upside down and sideways because as I’m sure you’re aware, these old arcade systems worked off of a mirror that was at a 45-degree angle. So you’re shooting into a mirror really with like a light. And so I dove into that. That’s actually when Claude took notice of what I was doing. He made some arrangement to kind of have me under his wing at that point. And very quickly, he was pushing me along.

Probably the earliest significant one was designing of the Space Mountain pre-show. He basically handed it over to me. He supervised it with wonderful guidance. And then he and by then I, John Hench, had taken notice of me and also Marty. And between the three of them, I said, well, let’s send them to, you know, later on when I was to be installed, watch over do the installation art direction as well. So that that was a great experience. And when I came back, they booted me upstairs to design office.

Dan Heaton: When you moved up to design, what was your experience working in the design area?

Rick Harper: That was so much fun because I was right next to that too. I was in a corner office and to the left of me was Al Bertino. And to the left of him was a wonderfully wacky, extremely talented young guy named Phil Mendez. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that name. Does that ring a bell at all?

Dan Heaton: No, it doesn’t. But please tell me more.

Rick Harper: Oh, he’s he was really something. A great character designer. He was a guy from New York who was brought west. If I think I have this right, I think Ken Anderson noticed his talent. I think Phil came out and did some in-between ing or something. But what his real strength was, character design. He was unbelievable at it. And so Ken Anderson actually had him living at Ken’s house for a while. And then eventually Phil bounced over to WED. He and Al were just hilarious together. They were they were like a storyboarding and gag team.

It was always, you know, laughs constantly from most off to the other side of me. If my immediate right was X Atencio, a wonderful man and just a sweet individual. He was a great mentor also. And next to him was Bill Justice. You just don’t get, you know, a kinder man than that. He was a great guy next to him, Rolly Crump. Then there was a conference from there that for a while was occupied by it periodically would be occupied by John Decuir, Sr. A mega talent if a name familiar to you.

Dan Heaton: No, it’s not actually. Oh, boy. There’s always more names for me to learn about.

Rick Harper: Oh, yes. Well, he came from the golden age of great movie productions of the fifties and sixties. I think he did a few things in the forties, too, but a magnificent production designer who thought very big and that’s another story often went way outside the lines of practicality. Then, you know, the rest of the designer would have to kind of pull these ideas into something that was doable. He was an amazing talent who wore a three-piece suit while painting oil paintings in that conference room. He was old school. I mean, this is if you’ve ever seen paintings of the 19th century masters painting, you know, they’re always in these three-piece suits. That was John.

Let’s see if I go around the room in my mind there. Next is Frank Armitage, a brilliant guy, amazing person and a great artist. Wonderful. You know this? These guys all came from the Disney culture of just I mean, they were all like, gentlemen and secure in their talent. You know, there wasn’t the insecure stuff that did appear. I did see some of that over at the studio. And occasionally it was odd. But this design group was a great group to work there next to them. Then just around the corner was Herb Ryman. Of course, Orlando Ferrante was in it and in an office that was very close by as well. Tim Delaney, another young talent, a great talent. And gosh, I think it goes on and on.

At another point, I was in an office next to Sam McKim, a monster talent and very humble individual. And of course, Randy Bright was just on the other side of me. Great guy to work with. And George McGinnis was another one that I had great admiration for and we spent many hours together. A lot of these people, these were not the ones I’m naming. These were not just, you know, guys across the way or in the hall. These are people I really got to know closely and some of them very closely, like Claude, Herb, and John Hench and, of course, Marty Sklar. Those four that I first mentioned, they were almost really like second fathers to me because I was less than half their age.

I don’t know if they were aware of it, but my father had died when I was in my mid-teens. I just sort of felt adopted by these people because they were always giving me, you know, chances and pushing me to higher levels. They showed a great deal of confidence in me, which I greatly appreciated. And, you know, gosh, it’s hard for me to go. I see you know, I know that you’re wanting individual experiences that I’m kind of overwhelmed with the whole.

Dan Heaton: You know, this is all great. So I’m curious, speaking of kind of getting put into different roles, when did you start getting interested in actually doing filmmaking? Because I know that you started doing short films and then commercials. When did that happen?

Rick Harper Well, actually, simultaneous in high school, simultaneous to doing the model. So I was making films in 16 millimeter. When my father died, he left behind a Bowflex camera, you know, a 16 millimeter camera. I became quite interested in making films. So, oh, gosh, during high school, I had made maybe eight or ten short films ranging in length from 3 minutes to maybe 10 minutes. They got a lot of notice locally because I became well-known for, you know, filming all around town and then having these little presentations at high schools. And that eventually led to me receiving an email, an invitation from Kodak for a contest they were doing for teenagers. I think it was called a Kodak Teenage Movie Award. So I entered five of my movies and four of them won awards.

That turned into a very exciting trip to New York, where there were all these press people and all this stuff. So then on my name started showing up in magazines and I got invitations to other film festivals, and then I started winning awards overseas. So by the time I, by the time I was hired at WED, they didn’t know and I didn’t think it was important at the time.

I had already gained about somewhere around 50 awards for these movies. Later on I began showing them these films. As I got to know people personally, I’d have little shows at WED, and then I was also doing films on the outside while I was working and doing commercials and whatnot. It eventually led to Marty offering me one of the Epcot films, so he gave me my choice, actually. So I jumped at the chance at the French film.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I can imagine that, because, well, I mean, it’s an amazing film. It’s easy in hindsight to say, well, of course you chose that one. But why did you decide that that was really attracted your interest more than the other ones?

Rick Harper: Well, along with being a real Disney fan, as a young person, I was extremely interested in 19th century art, particularly centered in France, because that was the epicenter of so many wonderful art movements at the time. And my mother had a really wonderful collection of books on that era. She was an artist and musician, as was her grandmother, and all of my mother’s sisters were. So there was a lot of interest and they were all really interested in that era. So there was a lot of influence from my mother in my interest in that. And also French music.

My mother was very cultured, and I grew up in San Jose. She would take me out of school. I mean, it’s great to take me out of school, you know, show up and say, I’m going to take work for the day. And then we’d go up to San Francisco to a symphonic concert. Generally speaking, it was French, you know, 19th century music. And so really, when I’ve been so interested in the French culture, yet I had never been to France. So when the opportunity came out to do that film, I really jumped at it.

Dan Heaton: The interesting thing about Impressions de France is that it feels so different than the other ones, especially that were there originally in China and Canada and not just because of the format. But like you said, with the music, I feel like it’s almost like you’ve entered this dream where you’re just floating around with friends with the music. Was it hard at all to get Disney to sign off on kind of this different approach where there wasn’t really, I mean, there’s a narrator, but there’s not really a narrator guiding you through it. Was that a difficult challenge?

Rick Harper: That is a very perceptive question, because, yes, the whole approach was different. During storyboarding and very early on, I was assembling long before there was a storyboard. I was assembling the music and wanted to do exactly what you described, kind of a dreamlike journey, a romanticized journey. I wanted to keep you know, I just didn’t want a lot of factoids; I didn’t want a left brain. The thing I wanted it to be a right brain experience and more of an emotional experience. On my little quarter inch reel to reel Sony recorder at home, I recorded all this stuff and then took it into the sound department and did some cross footage here and there.

Of course, those were the days where I would just physically cut the tape and put the recording tape and you just tape things together. I mean, much like, you know, the Beatles did later on their Sgt Pepper recordings, they had to do that. But anyway, so I had this little demo tape and presented it to Randy Bright. He was behind it early on. He went “this is cool” because he liked the fact that it was different. I mean, the music, you know, for someone like me, anywhere, the music really sells a lot. And I like to call it the secret weapon in a film. Then from there, it was convincing Marty, which took a little longer, and John eventually got on board with it.

There were some more severe criticisms from the studio, but eventually, by basically going through, starting by just going through a bunch of books on France and cutting out images and sticking them on the wall and rearranging them here and there, and then trying to figure out where these places were and, you know, what the history was. Coming up with something that felt like you were just being drawn to the film. An artist friend of mine way back in high school had said something really interesting to me that stuck with me while working on the storyboard for this. She said, certain art, whether it’s music, movies, writing, or paintings, certain art will draw you in and other art will push you around. I like the type of art that draws you in, and that was the goal on that film.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. You just think about the other films are great, but I think there’s something to be said that Impressions de France has not been updated. They haven’t come up with that. They haven’t done a new version. And I mean, just from the very beginning, you have that flute that shows up and then there’s the Normandy cliffs. And right off the bat. I mean, I don’t watch this film all the time. I don’t live in Florida, but I can still picture certain parts of the movie and I’m picturing them with the music.

And I think that’s like you said, it’s like the secret weapon to it. So while you were shooting, so you mentioned you had these cassette tapes. I know you’ve let me know that you had like a little cassette recorder that you shot on location. So how tricky was that to while you’re shooting and then you have this music that you’re trying to kind of get a gauge on how it would work? Was that a real challenge to do?

Rick Harper: Well, everything was a challenge with that camera system. Oh, my gosh. You know, the thing weighed 550 pounds loaded with, you know, these old Mitchell cameras on there. And by the way, the camera, a full load of film would only shoot a little less than 4 minutes. So then reloading the system took another at least a half hour if the other magazines had already been lowered into it. I took a cassette player with me and one thing that was just really a side benefit of doing that was I would play the music for the crew and this was a French crew.

Believe me, I came to really love the French people because they have art flowing in their veins. I mean, they just have a rich love for art. The crew members were just, you know, they loved the idea of the film. I took them through a storyboard and played the music and whatnot early on, and they really got on board with it. So then playing the cassette with certain scenes like the tilt up of the Eiffel Tower there, it became really important because the timing on that in particular was important with the way the music flowed. Other scenes involved some important timing, like, you know, some of the aerials did. So in those cases, the helicopter makes a heck of a racket. It was just a matter of timing, you know, timing the shot and working that out with the pilot.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, because there’s so many scenes where, whether it’s a hot air balloon or whether they’re flying towards a castle, where the music does seem to fit right with it. Some of those scenes are only I mean, what ends up in the finished film, I know you probably shot a little more than 30 seconds or something, so the timing is crucial. I’m impressed you were able to do that. You mentioned the camera. So you know how you sent me some pictures of the helicopter and the camera. I mean, how does how do you wield it? It’s not like now where we have these image of either if there is a camera or something you could walk around with or there’s phones or digital cameras. How do you wield that and actually perform as a director when you’re making a film?

Rick Harper: Well, it involves a lot of gymnastics for sure, because you got to climb all over the first of all, the camera, you can only see one frame at a time in the view. You may have noticed in some of those pictures, I’m looking through an eyepiece low on the camera system and that one eyepiece covered in just the range for one view. You know, the mirrors are broken up. So are set at different angles on that thing. Plus, because you’re looking through a mirror, you’re looking at the image backwards. So lining up a shot was really complicated because you didn’t want and I always tried to include some movement in the shot. On very few shots in a film, you don’t have the camera moving.

When the camera’s moving, you run into the danger of something winding up along the dividing lines. That is awkward visually. For example, somebody’s standing there or, you know, something that has lettering on it, and instead of spelling, you know, the right word, it spells a shorter word because it’s on this dividing line and things like that or even anything that may look strange, divided because it wasn’t perfect. It didn’t come to a perfect match on that. So that was a big issue. It took a long time to set these things up. And very often there were while two camera systems were frantically reloading. Joe Nash, the camera assistant who was fantastic, totally reliable, knew every single thing about that camera. He’s also an engineer and wonderfully supportive.

He was always looking over the camera and he was very possessive of it. He finally allowed me to set some of the other stops and to move the camera with him and mess around with it. Because we had to rely on each other under the time crunches. Another thing was we often were shooting, I mean, because shooting was film in those days, we were shooting with a speed of 25 on a lot of this, That translates into having to shoot in very bright light. But I always wanted things at the beginning of the day or end of the day or in a twilight hour where there was just more of a warmth or a twilight effect to bring more of a romantic, you know, feel to the imagery. So we were very familiar with frantically moving to capture these times.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s interesting because I think of like one of those really early scenes when you’re kind of moving along the waterway. It does feel like it’s like the very start of the day. If that was right and it seemed like it was noon, it would not have that same effect. So I hadn’t even considered that. How not only do you have to shoot with this massive camera and the mirror thing as not being a filmmaker, my brain can barely process how you even did that backwards.

So I’m really impressed by that. But it’s just a testament to how well everything was put together that that happened. So you mentioned getting out the book and looking at the places. I’m curious because I feel like you could find 100 places in Paris, and that’s one of the few places in France I’ve been. But how did you narrow down beyond the, like, Eiffel Tower and Versailles and all that? How did you really narrow down the places you decided to film at?

Rick Harper: We had to go there physically and just really examine the situation there. Because this camera shoots basically a 200-degree panorama. So it became important to establish, okay, can we actually shoot here and not have a nuclear power plant on a shot somewhere or you know, some ugly wires or whatever. In some cases, we had situations like that that found some creative solutions to those problems. But getting out and really seeing the different areas of France, it really helped a lot. And to narrow it down quite a bit. The shot list became pretty darn specific. There are a few grab shots in the film, believe it or not, with that camera, because I don’t like sitting around waiting for weather to change or the wind to come down or whatever.

So I would often just create a shot where we were stuck and some of those wound up being used in the film, the older couple on the top of those cliffs, etc., That was a grab shot done in a light rain when the crew was hanging out in a local tavern. And I’m going, dang, I want to shoot something. But then the idea came to me to take that on to the end of the wedding sequence, and I went running down into the village and got her to come up on the hill and we we threw that shot together.

The old couple was a couple that was in a tavern with the crew. You mentioned the shot of the guy chopping wood. That was another another one of those things we’re sitting around waiting for someone to deliver the bicycles for that bicycle shot. And they were late. I wandered off into the local piece of property across the street and watches. This would make a wonderful shot. So the guy chopping the wood is our lead crewman, Rene Strasser. That wound up on the film there with a couple others like that.

Dan Heaton: That’s so interesting because what gets me also about this is all the little scenes like that. Like, you know, yes, we have the big majestic moments, but the guy chopping wood or the wedding or the village and that interested me. How much was that on your mind, though, when you were create I mean, before you really dove in of kind of capturing these little moments within all of the big grand monuments and stuff?

Rick Harper: It’s very much on my mind and that’s why I was always on the lookout for an opportunity to to grab something like that. The wedding was very much planned and took a lot of planning and the filming of it. I think you can tell from seeing the stills there was a heck of a lot involved with that as well. We really wanted to get the intimacy along with the grandeur, definitely. And going there and meeting in a lot of the cases during the scout meeting, some of the local mayors, and getting to know some of the villagers where we were, we want to in some cases, these places we wanted to film were owned by locals and getting to know them.

For example, the wedding scene where they were, it’s like the reception at the end where they’re in Brittany and it’s at night and there’s this, you know, traditional dance going on there. Scouted a lot for a place where that could be done while driving around, looking at farms down these little dirt roads. And we run this one on going, okay, I think this will work. We knock on the door. A guy comes out, you know, I’m having to work through the translators. I noticed that he was where I swear this is true. I have pictures of this; I should send them to you as I’m talking to you. And I look down and I see that he’s wearing wooden shoes with straw and instead of socks.

Now this is like classic out of a 19th-century painting. So I quietly took my camera and kind of while talking to I aimed it down at his feet and just seemed like so sad. Anyway, so we got to know and thought, we really want to get to the feeling. The rural, you know, Parisians are very different. It would be, if we were doing a film about France and included only Parisians, it would be like only including a big metropolitan area and not getting into the rural area areas.

Dan Heaton: Right. Then yeah, wouldn’t really get what France is. I mean, Paris is a big part of it, but it’s one little part. You mentioned the bike riding scene, which is still one of my favorite scenes of where basically it seems basically you get this feeling, especially when you’re seeing it on the big screen, that they’re like chasing you down and somehow you’re riding backwards, you know? I mean, how true, how did you film that? Like you’re on some other vehicle. How did that all come together?

Rick Harper: Well, that was basically the camera was, in essence, on the back of a pickup truck and much like I think I included shots there where we were, where I’m kind of crouching down while we’re filming the French Republican Guard there on horseback. I don’t know if you saw that image. It’s in there somewhere. But yes, it’s the same kind of thing. It was just on the back of that truck and we told them, get as close as you can. The driver was very astute. And by the way, all those bicyclists are just our crew members. So it gave them a chance to be on the screen.

Dan Heaton: Oh, you’re just destroying my thoughts on this. I thought that it was just some French locals who happened to be riding.

Rick Harper: Oh, really? They are, in a way, because they’re all French, with one exception. Charis Horton, who is one of the bicyclists. She nearly goes off the road there at one point. But she was an American who married Frenchman Antoine Compin, who was a brilliant production manager. The two of them were absolutely brilliant, amazing, with different talents. But as they work together, incredibly and so it was it was fun to get them all on there and try to catch up with us.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that’s a really fun thing. And it brings a lot of life to the movie. So on a completely different level, you mentioned the Eiffel Tower. So I have to ask you about that shot because the feeling of scale when you’re having the Eiffel Tower is in person, as you know, seems so much larger that it does in pictures. You do a good job of capturing it. But tell me about that shot. We’re basically I don’t know if you’re in I assume you’re in the elevator, like you’re basically going up the side there to put that on the three screens. It seems mind boggling.

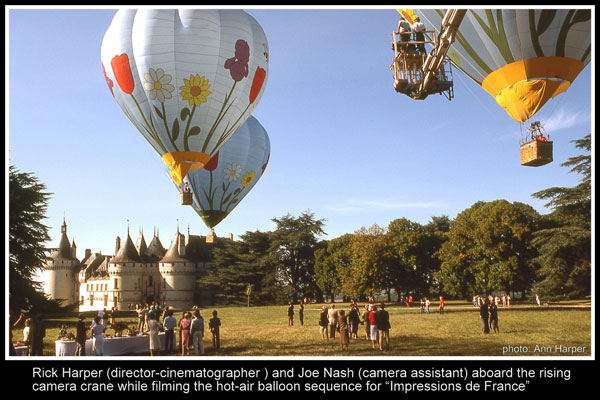

Rick Harper: Well, first of all, the tilt up shot was done from a crane that was about it was the same crane we used for the balloon lift off scene, which, by the way, might be an interesting scene to discuss as well. But the crane was probably up, I would say. I can remember here, it was probably up about maybe 150 feet in the air for that tilt up shot. It had to be positioned exactly so that when when I tilted the camera up and I I had to physically do that, there was no mechanism for that.

I had it just tilted by way of a brilliant device, cradle actually, that Don Iwerks came up with another man who was wonderfully supportive on this project because I wanted to do a lot of crazy things. And he said, Yeah, you know, I need to figure something out that it was important to get started at the level, you know, so-called level and then tilt up and then have a frame to get the massive nature of it across all those screens and then dissolving to the shots where we were actually on top of the Eiffel Tower elevator.

One of them, it was pretty harrowing because the first it gets a bit technical and long, so I can’t quite go into all of it. But the first testing we did nearly ended in a real calamity where there’s a huge mechanism that, you know, the Eiffel Tower has tilted legs, but the changes it, it’s tilted maybe at, you know, 60 degrees at the beginning and then it goes gradually into, you know, vertical. That’s a complex mechanism that involves these huge moving parts. And some of those moving parts almost swept us and the camera right off the top of the roof in while we were trying to make radio contact with the engineer down on the basement running the whole thing, it was pretty scary. Oh, my gosh. We finally got all those bugs worked out and got the shots that we wanted.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s great because the shot is is amazing. But yeah, that’s the thing that, you had sent over the images and a lot of the images, whether it’s from the car race or everything, you’re always kind of hanging out. It’s a weird spot or like, you know, a tarp or something. And I’m like, were there regulations at this point? You know, because it leads, I think a lot of that to what leads to the film being so good. But it’s so interesting because when you watch the movie, you have no concept of how that’s going. You mentioned the balloon scene, which I love. Tell me a little bit about how that came to be there.

Rick Harper: Well, the serenity of that scene is it took a lot of utter chaos to achieve it. Just boy, how can I do this briefly? First of all, getting that there’s so many variables and technical issues. The camera, getting us a crane that would move smoothly. I mean, this was a construction crane and we tested I don’t know how many dozen cranes in Paris to see which ones would be capable of moving smoothly. There was this one that was working, you know, pretty well. So we wound up using that whenever we used a crane. But bringing that out to the lower valley in front of the castle and getting the thing to function right was in itself a matter of hours to get that right. Then there the weather was changing constantly, of course, so it was another thing.

The balloons, I placed them all in different areas and working very closely with the primary balloon pilot and the owner actually of that balloon company whose name was Buddy Bombard. Colin Campbell introduced me to him and suggested I look into working with this guy. So I went up to call on about that. They had to in order to set up the rehearsal. And of course, there’s all of you know, there’s this table and all these people and food and, you know, costumes and all that stuff going on and in the midst of everything else.

But the balloons themselves had to be kept inflated just enough to keep them manageable on the ground, because as the wind would change a little bit, I had to have them, you know, I’d say, yeah, we got to walk this one over here a little bit so that by the time it gets up in the air a little bit, it isn’t blowing straight into the camera and knocking us over or whatever the conditions were.

Occasionally, as a gust of wind came along, one or two of the balloons would kind of collapse. I don’t know if you can picture this, but it’s like they’re made of this flimsy material and they kind of just they just sort of collapse. So that became chaotic and some of the pilots grew a little tired of what was going on. And the crew kept the vision. We got through the first day of set up and rehearsal. Then it was a matter of on the second day trying to nail a take that would work. We had to do a few takes and then keep in mind that changing the camera load, we only got four minutes, which meant technically we only got at best two takes out of each load, and then when the balloons take off, they have to be brought back again in vans.

They had to be deflated, brought back and farms re inflated, etc.. Meanwhile, we’re getting the camera ready for another round. So day two was a matter of shooting a number of, the weather was changing constantly. Clouds were coming in and you know, I got to have sun for this. It’s got to be either early sun or late sun. So we started setting up in the dark misty early due to either cloudy weather or balloons collapsing on each other or something. Finally, at the end of the second day, the magic came together and we got that shot. It was such a celebratory time for everybody, believe me.

Dan Heaton: So that raises an interesting question. When you’re doing all of this and you’re trying to get the right shot, when are you able to actually at the time and this is probably my lack of understanding about that time period, how film making works. When are you actually able to go back and look at what you shot that day?

Rick Harper Gosh, these are great questions. I mean, that was certainly a thorn in our flesh all the time, because this because the different loads of film had to be matched in the old days of film. Film was processed in labs where every batch was a little different, every chemical batch was a little different. So you couldn’t rely on any two reels looking quite the same in terms of the color sense about them. This was just something that people had to accept about movie making, and then later on you would do what was called color timing, where in the lab before the negative was made, you would make an inner negative by, you know, putting different filters in front of the different shots to get back to the look that you thought you were getting when you shot.

Well, when you have five cameras that have to match, it becomes extremely important that they’re all run through the same chemical batches all the way through the process. So the one lab that would take the sun was Technicolor in Hollywood. And we knew we could trust them. They had a great relationship with Disney. So all of this footage had to be sent back to California, processed and then viewed at the studio. They could only view three screens at a time. So it had to be viewed, you know, there are five cameras.

So it had to be viewed the three left ones, the middle three and the right three ones to make sure things were matched. I had an assistant at my office that I trusted completely for his very sharp eye, and he would go to the studio and look at the stuff and then call me right away. Yeah, you got it. Oh, boy. You got a problem here or there. Scratches on this rail. What do we do about that? Or there’s vibration in this helicopter show. You got to redo that. We had that happen a couple of times in two cases. I had to fly back to California to kind of really brainstorm, you know, what I was going to do about this.

Dan Heaton: Wow. All of that just makes the finished film even more impressive to me, though, you know, because I’m sure I knew that you didn’t. It’s not like you have like now where they have the digital monitors and stuff. But I still I didn’t realize that and the fact that you didn’t, you know, obviously Epcot’s theater was not ready. There wasn’t even a five-screen place to watch it. That’s a crazy adventure.

Rick Harper: Eventually there was. And again, thanks to Don Iwerks eventually, as I mean, the filming took place across, oh, golly, probably nine months. That doesn’t mean we were filming for nine months. It meant that there were breaks in between where we had to, you know, line up other things. In some cases, I had to scout for alternative things or whatnot, but and fly back to California sort of stuff with production. And budgetary issues, I’d sort it out. I think there were four different shooting going, maybe five anyway across that nine-month period with breaks in between.

So that gave me a chance to for the latter part of that dawn, I think for the last, you know, couple of shooting periods, I was able to go back and actually see the five-screen results. That was a great relief to be able to see them all at once during those periods. Also, I would work out rough edits of some of the material to see how it was coming together.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, they had to be really helpful, I’m sure, to get to actually be able to edit it that way and start to head in that direction. I wanted to circle back to the music real quick, though, because I know that, Buddy Baker was involved, who’s a well-known Disney figure, and I know more involved with the arranging, not with like, you know, the choosing, but then creating some additional music. So what was it like to work with Buddy and how did that work out?

Rick Harper: Well, it was another dream come true because knowing his deep history and his great talent, he was assigned to basically do music for Epcot. And so when that assignment was announced, I approached him right away and laid out what it was I wanted to do. I had not met him before this time, and I didn’t know what to expect. I thought because some composers really don’t like in general. They don’t like a temp track being thrown at them and say, match this, you know? But I wasn’t asking him to match it. I was asking him to use it. And by that time I had over 80%, 85% of the film music kind of worked out.

He listened to it and he said to me, well, you know, it’s such a relief. Well, I happen to love this music and you’ve done me a great favor, Rick. He said, I’m so up to my ears. And he said, I think just wonderful. So we’ll work it out. There were areas on it on the tape I played from were indications for needs of transitions In a couple of cases, key changes were needed to be done.

I had done edits on some of the music that actually rather confounded the arranger and Buddy. They worked all that out, but he just did a wonderful job of creating the transitional music and carrying the feel. He really had a heart for this film and he had a heart for the music, and it really came through and it came through also working with him under very stressful conditions, recording at Abbey Road Studios.

We happened to record on the day of the worst snow storm in like a hundred years in London. All the musicians had horrifying, you know, exciting stories about how they showed up. But the recording sessions started, I forget how many hours late, but really late. There were technical issues due to the freezing weather as well in terms of the studio, you know, electricity and all that kind of stuff. It was pretty wild. But Buddy was just a total pro and a gentleman, delightful person, great sense of humor and total joy to work with.

Dan Heaton: Well, that’s great to hear. So you mentioned Abbey Road and recording with an orchestra there. So what was that experience like?

Rick Harper: Well, I’ve recorded a few times with orchestras, and let me tell you, that’s a thrill to have. That’s that’s a thrill because on the screen, of course, in this case, we were only projecting the middle screen to kind of keep in his head while conducting. But you really when you record the music, it’s magic. It really is. It was also very thrilling trying to get home because the airport was completely crammed with people.

The airport had been shut down. I know it’s a crazy story, but anyway, we did it. And Glenn Barker, by the way, was there and magnificent. He’s another guy that never loses his cool. He just has this dry wit about him, very sharp mind. He’s the guy who spearheaded the idea of recording digitally, which presented also a number of challenges at the time because we were working with a prototype machine that had been flown in from Japan.

There were only two in the world at that time. Sony had come up with this digital thing. There was one in L.A. and one in Japan. I think we got the one from Japan. Even the Abbey Road Studio guys were going wait a second, what are we dealing with here? So that there was a learning curve. This whole film involved quite a learning curve because every step of the way we were trying to kind of push the envelope on the technical stuff.

Dan Heaton: Well, I think that that shows, though, because it doesn’t feel like a movie that was shot in the basically late seventies, early eighties. It’s basically still holds up really well. And that’s kind of my overall, I guess I’d say last question about a present to France is, you know, people were really concerned. Disney recently announced they’re going to do Ratatouille right there. And everyone’s like, Oh, now they’re going to close Impressions de France, especially the fans, and they’re not which surprised me actually, pleasantly so just because of kind of trends in the industry. So why do you think it’s held up so well where even Disney would decide, hey, we want to keep this? Like, what is it about it that makes it so timeless for you?

Rick Harper: Well, it’s funny. The goal at the time was to try to keep this as undated as possible with the visuals as well. And to achieve that, there were different tricks used, I mean, on the shot or say, for example, when we’re driving down to the Arc de Triomphe there in Paris, you know, the shot in twilight and to kind of help obscure the fact that, you know, these cars are eventually going to look really old someday. And anyone who’s into cars is going to notice right away. But the hope was I remember telling Randy, I’m really, really wanting this to play for a decade and possibly more and take that approach to it.

So it’s just really fun that it’s managed to last as long as it has. As far as your other part of the question or the you know, people call me from because I keep in touch with people that Edward and whatnot. I’ve gotten some interesting calls were you know people tell me, hey, you know, there’s a rebel group here that’s, you know, trying to keep the French film. And I go, well, that’s cool. So apparently there’s kind of a little uprising among certain Imagineers along the way that have kind of taken the issue upstairs.

So I guess it’s sort of I thought it’d be gone long ago, but I’m happy that it’s stuck around. It’s an interesting thing, though. I heard the other day that I think they came up with a really smart idea. They want to get some dual use out of that theater, right? Yeah. I think there was a somebody sent me an article about they’re going to do some kind of a Beauty and the Beast music stage presentation of some kind.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I think it’s like a sing along, I think. I’m not sure I understand. But I think, you know, Don Hahn, who is supposed to be involved with it. So it can’t just be like putting the movie on the screen. But I hope that they’re able to do it, like you said, as a dual use. You know that the warning bells go off in my head that go, yeah, you know what if this is more popular because better but you know, it’s Beauty and the Beast.

Rick Harper: Yeah.

Dan Heaton: So I get a little nervous and I’m thinking, okay, you know. I have to understand things do change at theme parks. And like you mentioned, I mean, do you think about it? The film in Canada, they did with Martin Short and now they’re going to redo again the film and China was redone. They’re going to redo it again. The fact that Impressions de France is still there as as an opening day attraction, there’s not much left from opening day at Epcot. It’s incredible.

Rick Harper: Well, it’s certainly been been fun to see that it lasted long as it did. And as far as the sing along, I think it’s a good idea. See, I have a five year old granddaughter and I know that she would go nuts for the Beauty and the Beast singalong. I have no doubt about that. And it’ll probably be a great draw. I guess the idea is to alternate, right? It may eventually turn into, two or three of the Beauty and the Beast shows, you know, to one of the French film thing. But all of all things must pass, you know. So it’ll eventually be gone.

Dan Heaton: If it’s a way to keep Impressions de France, and if they’re only going to show it three or four times a day or whatever, and it stays, okay. I’m okay with that. So I wanted to ask you about a few other things you worked on here. So I will get to American journeys in a minute. But I have to ask you, you shot this commercial of Space Mountain and you sent me this picture, which is basically you sitting on Space Mountain holding a handheld camera with this crazy face on it. And I don’t understand it at all. So explain this commercial to me.

Rick Harper : That is a gag shot. It’s a total gag shot. And by the way, this is my wife sitting next to me there. Oh, and the first of all, the commercial is, it’s just so crazy. It was done on the fly. I was still working at WED and doing, you know, film projects and including commercials and some like promotional films and things, educational films on the outside. The opportunity came along to do a Space Mountain commercial, and this is unbeknownst to WED. I went, okay, I’ll do that. And I really wanted to do it. Another commercial was shot over a long weekend down at Disneyland using the loading area or the exit area. I think it was yeah. At the time that was partly still under construction.

So we had to shoot from like, you know, eight at night to six in the morning. The model of Space Mountain, we used that. That was down there also in a warehouse and lit that model and use that as part of the opening of the sequence and then there was an effects shot in it that was shot in a warehouse with one of the cars on a teeter totter. I would dolly past the arrangement, this mechanical arrangement with the vehicle on it as it was being tilted by a crew member dressed in black against a black background.

The people, the actors were supposed to go “AHHH!” as the thing appeared to be moving along and tilting and going down. So then eventually with an optical printer, put a starfield behind all of us. Just as a gag shot. Again, we were shooting all this stuff in the middle of the night because we didn’t want any light leaks in this warehouse from daylight and whatnot. So at the end of that shooting, we were all kind of bonkers and just did that gag shot.

Dan Heaton: Well, that makes more sense.

Rick Harper: Like, nothing was shot handheld.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, you didn’t, like, write it and shoot it that way. Well, it’s funny because you mentioned kind of the manual way. You had to kind of do some workarounds. I’m not sure they’re still there now, but the safety videos that they have, even at Disney World that don’t look like I mean, the probably were shot in a similar way because they looked very fake, like they were shot in front of like an effects screen. So because they rarely I think like for something even a commercial, they don’t just put a camera on it and show the whole ride or something.

Rick Harper: Well today it’s more likely you can do it with I mean it’s amazing what you can do with virtually no light and no weight to the camera and no limit to how long you can shoot. It just I mean, it’s a different world. This stuff was, it was very bulky, crazy stuff.

Dan Heaton: Well, I want to ask you about one other thing. This having to do with Disneyland in it looks like you also shot footage for the speed tunnel, which unfortunately Disneyland doesn’t have their People Mover operating anymore. But when they had like the speed tunnel and I love just to say speed tunnels in general which used to be like they were in Epcot and World of Motion, they had them. And If You Had Wings, though, I know it’s Buzz Lightyear now, but they were common. So how do you shoot something like that? Like you were out in the desert and, you know, how did that go?

Rick Harper: That was fun. And that was the first. After making the Space Mountain commercial, if I remember right, I showed the Space Mountain commercial and really quickly after that, Marty said, heck, let’s have them shoot this speed tunnel thing. So that was a wonderful opportunity because Art Cruickshank was part of that. And he’s a man I had greatly admired for his work as a special effects pioneer over at 20th century. But then Disney snagged him and brought him over to Disney. He was the director of photography on that. I did the directing and it was just we put two VistaVision cameras on different vehicles, one arm forward and one arm backwards, and then shot all these crazy things of moving quickly by other things coming toward us.

In one case, it was the Everglades boats, with those huge propellers on the back. And actually, we had a really serious accident with one of those. That’s a funny story, actually. The footage came out really well. Art and I had a wonderful time together. So I met a lot of wonderful people on that. And it was right after that that Ron Miller actually, along with Art Cruickshank, offered me the job to take over. Art was going to retire soon and Art was the second unit director for the studio for the feature films.

And I turned down Ron and he got really upset with me. And then he later, you know, calmed down. He said well actually I respect your decision. So that eventually led to where I kept in touch with Ron and showed him the things I was working on. By then, I was doing a lot of things on the outside and I just wanted to keep doing that. So eventually that led to the French film.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I kind of circled back and then in time for the film, but that’s okay. That’s an interesting story. So you mentioned the Circle Vision film, and I wanted to make sure I mentioned American Journeys. And I’ll admit, I know that I saw American Journeys, you know, at Disney World or Disneyland as a kid. And I watched the YouTube videos, though, because it’s no longer playing. So they’re a little hard to see. But just that circle vision film and, you know, very different shot, after Impressions de France. So tell me a little bit about shooting that and some of the differences with having to actually do the full Circle Vision.

Rick Harper: Well, it was tricky because on the French film, we were continually raising the bar on what you could do with this camera and part of the ability to do that. Part of the rationale when I was trying to sell the idea of doing a five screen film instead of a Circle Vision film was part of the rationale was, well, you know, with those four back cameras missing, we can use a crane, we can we can mount on different types of vehicles.

We can achieve things that have never been achieved with these Circle Vision cameras. I mean, previous to that, the cameras were shot primarily from a DC3. You know, aerials were done from a DC3 plane that was flying 15 miles above the earth. You couldn’t get close to anything. And on the ground things were shot, usually from a public street on with the camera mounted on top of a station wagon.

So we really wanted to get away from that and get more intimate with things. By doing that on a French film, it was expected now on on American Journeys, but it got a lot more complicated with those four additional cameras on the back. So that was a challenge. But it was a fun challenge because I had to come up with a lot of creative solutions for that to try to match that level of technical achievement.

Dan Heaton: Are you saying you spent more time kind of like standing on weird vehicles and hanging out of things?

Rick Harper: Oh, definitely. In fact, I learned to sit on top of the camera. Joe devised a little platform up there that I could sit on so I could see what was going on and, you know, look all around. And very often, I mean, because it really yeah, you have to clear everything out of the way. And of course, shooting in public, people don’t realize, for example, in the aFrench film, anything that involved people had to be completely staged from the ground up. I mean, the market scene, for example, we had to take over a little town completely, and that’s the way it was. And then American Journeys almost. Well, otherwise, you got people staring at the camera on that kind of stuff, right?

Dan Heaton: Because you think about like now, like the newest Soarin’ film that, well, one, they use some computer generated imagery, but also they can just digitally take people out. You couldn’t do that back then. So you were kind of now I wouldn’t say stuck, but you had to almost have a controlled environment.

Rick Harper: Oh, completely. Yes, absolutely. That was and in some places, you know, like the fireworks at the end, for example, on the Statue of Liberty Island there, we had to completely take over that island and take over the we had to get the local, you know, air controllers and aviation authorities to agree to not have anything fly in that area for about a four-minute period while we were trying to shoot, which was right at that key moment at the twilight where the fireworks would show up really beautifully against the deep blue sky. And we had to control the harbor traffic.

Dan Heaton: Yeah. It sounds like the filming part is like, oh, that’s the fun part. But all the logistics and preparation is like 90, 95% of it or something.

Rick Harper: Well, this is where I have to really credit Charis Horton and her husband Antoine Compin, and they were amazing. I had to lobby heavily to bring them over from France to be the production managers on American Journeys. So because I thought these people are amazing and they understand the issues with this camera system. One way, push it, you know, push the envelope on it. And eventually the studio bought into that idea. It was a little tricky, you know, getting around the union issues and whatnot. But I was awfully glad to have them along because they they were amazing at working out that kind of stuff.

Dan Heaton: I mean, it sounds like that’s so important to making a great film. Impressions of France is gorgeous, But all the legwork you had to do, I’m sure, is the only way it could be that way.

Rick Harper: Yeah.

Dan Heaton: Well, this has been amazing talking with you. So I just have one last question. I know I believe you retired from doing films officially, but I know you still do some artwork. So how do you spend your time now?

Rick Harper: Well, I’m definitely a family man. And moving to Carmel, California, in the early nineties, I continue to do a lot of film projects. I did some things for big screen films, for theme parks and attractions in Taiwan and in Japan. And I also did 3D films and Motion Seat 3D films and as well as following my love of art history. I got involved doing the special films for the National Gallery of Art. I did three films for them and other museum films, so very busy. And then I reached a point where, you know what? I’m ready to just go paint and be with my family. So I did that in 1992. I moved up here and it’s a good life, believe me.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it sounds good.

Rick Harper: You know it.

Dan Heaton: It’s it’s very cold here today in Missouri, so I’m all jealous of that life.

Rick Harper: Oh yeah.

Dan Heaton: Well great. I love Impressions de France and a lot of your other stories and work. I mean, it sounds like you had just an amazing experience working at WED and at Disney and I really appreciate the time. It’s been amazing to talk with you, Rick.

Rick Harper: Well, thank you. I appreciate your interest very much. And I’m a bit of a recluse when it comes to interviews. So you’re a very kind personality. Kind of won me over to to get pulled into this. So thank you.

Dan Heaton: Well, great. I’m glad it worked out. It was so much fun.

Rick Harper: And if you’re ever out our way, please don’t hesitate to contact. We’d like to show you some beautiful sites out here.

Dan Heaton: Oh, I will definitely do so. Don’t worry about that. Thanks so much.

Rick Harper: You’re welcome.

Leave a Reply