Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

It’s an exciting time for Disney history fans. Many Imagineers from the ’80s and ’90s finally have the chance to tell their stories. This second generation joined the company for the opening of EPCOT Center and worked directly with legends from Walt’s time. As the company expanded under Michael Eisner, these Imagineers took center stage. A key figure was Tom K. Morris, who worked at Disney for more than 35 years.

Morris is my guest on this episode of The Tomorrow Society Podcast to talk about his career and a lot more. It’s clear that he’s a big fan of the parks and their history. Morris sold balloons at Disneyland when he was young, and he approached Imagineering as a fan. His recent appearance at Midsummer Scream showcased his fandom for The Haunted Mansion. We start by talking by that iconic attraction on its 50th anniversary.

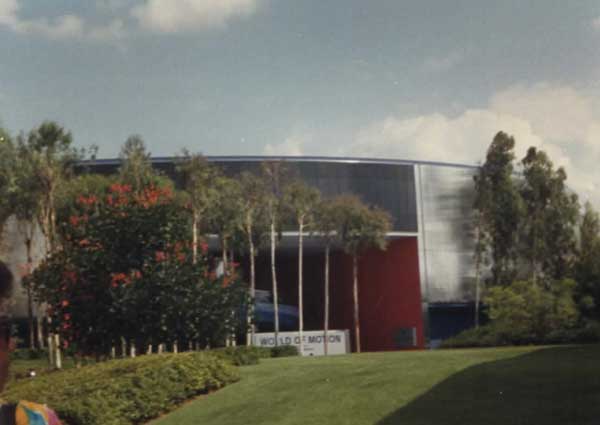

We also cover Morris’ work on EPCOT Center, especially World of Motion and his extensive role in the original Journey Into Imagination. He worked on the design for the turntable, which set the scene with Dreamfinder and Figment. Another big topic is Morris’ design for the incredible Sleeping Beauty Castle in Disneyland Paris. Morris was the show producer for Fantasyland there during an exciting time at Disney.

I loved the chance to speak with Morris about more than just his specific work at Disney. There is plenty more to cover from his career, including Hong Kong Disneyland and Cars Land at Disney California Adventure. Morris is also working on a book about the early days of Imagineering, and it sounds like a fascinating project.

Show Notes: Tom K. Morris

Follow Tom on Twitter and Instagram to keep up with his book project and interest in Disney history.

Watch the presentation from Tom on the Archaeology of The Haunted Mansion from Midsummer Scream 2019.

Transcript

Dan Heaton: Hey there. Today on the podcast we’re talking about the 50th anniversary of the Haunted Mansion, Journey into Imagination at Epcot Center, and Fantasyland and Sleeping Beauty Castle at Disneyland Paris plus so much more with former Disney Imagineer, Tom K. Morris. You’re listening to the Tomorrow Society Podcast.

(music)

Dan Heaton: Thanks for joining me here on Episode 81 of the Tomorrow Society Podcast. I am your host, Dan Heaton. One of the things that really fascinates me about the eighties and nineties at Disney, often known as the Disney Decade when Michael Eisner was in charge, and even before that with Epcot, is this new crop of Imagineers that took over and they were different than the old guard because they were fans first. A lot of them had grown up going to Disneyland, and that drove how they approached the parks, and you saw it in the way that attractions were built during that time.

A lot of them are still considered classics to this day. I mean, think about the story of Tony Baxter going to the parks and being so invested in everything and kind of just finding a way to work there. Or I recently talked to Tim Delaney about his obsession with Tomorrowland and the future and the “Man in Space” series and how that led him into his career.

That’s also true with today’s guest, Tom K. Morris, who recently was involved with a panel at Midsummer Scream about the 50th anniversary of the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. He also did his own presentation focusing on the archaeology of the mansion. What I find so interesting about this is if you look at the way Tom talks about the Mansion and about the parks, you could easily assume he’s just a scholar or somebody who’s really invested in the history of Disneyland, and he’s actually writing a book right now about the early days of Imagineering at Disney. So it all kind of fits together.

That sets aside the fact that Tom worked as an Imagineer at Disney for a really long time. I mean, he started out selling balloons in the park and ultimately ended up working in Imagineering for the Epcot project involved with World of Motion, and then more specifically with Journey Imagination and worked on so many big projects for Disney, including, like I mentioned, the Castle design at Disneyland Paris.

He was also the show producer for Fantasyland in that beautiful park, and most recently he worked on Radiator Springs Racers at Disney California Adventure, which is a real standout in that park. So we had a long career at Disney as an Imagineer and also has that interest, which if you follow him on Twitter, you will definitely see in the history of the company. So it was really exciting for me to have a chance to talk with Tom and delve into a lot of different issues about the history of the company and also about his career and what it was like to actually work there. It was great to talk with him and learn more about his story.

So I really enjoyed talking with Tom. I’ve heard him on other podcasts like the Season Pass and the Themed Attraction podcast, and I really appreciated him taking so much time to talk about his background, but also to dive into what interests him about the company and especially about Disneyland. So let’s go talk to Tom K. Morris.

(music)

Dan Heaton: I want to start with the Haunted Mansion because I know just from following you on Twitter and other social media that you’re a big fan of the Haunted Mansion and it just has its 50th anniversary, and I know you are a part of a panel at Midsummer Scream about the Mansion. So just upfront, given this big anniversary, why was it so important to you when you were younger?

Tom Morris: Well, I was at that impressionable age when the house rose suddenly one summer we went every summer. My family and I, usually on the 4th of July, and I remember this was probably in ‘63, we were eating at the patio of the Pancake House, and I was impatient and felt like I needed to not be sitting there looking at pancakes or whatever it was. So my dad told my sister to take me for a walk and go look at that new haunted house over there. Oh, cool. That’s neat. Haunted house. So I was only four years old, and we went up there and it’s like, well, how come we can’t go in?

Well, because it’s not open yet, it’ll be open soon. So I just kept looking in there and it was intriguing to me because it didn’t look like a typical kind of monster house or anything like that. It’s just looked like a nice elegant home, I guess. It just peaked my imagination. Then every year we’d go back and we’d go over there, and it still wasn’t open, but it’s going to open soon because it said so in the guidebook or in some brochure or something. And well, how come it isn’t open? That’s kind of weird.

This went on and on. Then rumors, of course began to circulate, and those rumors predate the Internet and social media and all of that, and they were very persistent rumors. So all of that was something that I think just stimulates the imagination of a young person. Growing up in Orange County, I mean, I think everyone in Orange County and Los Angeles County nearby areas kind of went through this same thing if we were the same age, it’s like, when is that going to open and why isn’t it opening?

So I think that’s why it has extra special meaning. It’s not just another great attraction, it’s kind of a mystery in addition to being a great attraction. So when it finally opened, it was something really to pay attention to and to celebrate.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s one of those interesting attractions where I know when it opened Disneyland’s attendance and everything just took off. But I feel like now, I mean, just judging by the interest, it seems like it’s growing now, which to me is Pirates of course has a similar kind of trajectory, but it’s rare to have an attraction that’s been around 50 years that has been so popular and then continues to grow, I feel like keeps finding new fans and they make changes and it’s good. It’s crazy.

Tom Morris: Yeah, I think the Internet had a lot to do with people discovering that there were other people that enjoyed the attraction so much. I almost said, have this affliction, but it kind of is an affliction. I thought I was the only one; I think schoolmates and everything were intrigued and when is it going to open and oh, that’s really cool.

But then I kept, it was an obsession for me to figure out how all the effects were done, and I just loved the music and the style of it, the design of it. So for me, it was a little extra. So I would sneak a recorder in to the park, a little portable cassette recorder, and I’d record it. I would take pictures, not flash pictures, but I think I brought a tripod in one time and took time. Exposures of the haunted portraits in the hallway there.

It was a little extra. I wanted to get merchandise, but there was really no merchandise back then. You couldn’t buy the poster, you couldn’t, there really wasn’t anything. There was that magic book that I’m sure you’ve seen that didn’t really have much in it. I expected that there’d be a booklet like they did for Pirates of the Caribbean on the Haunted Mansion, and that never happened. It took years and Jason Surrell to finally create that book.

So there wasn’t a lot you could leave as a memento or a souvenir. So it was kind of up to you to take photographs and I would try to figure out what the track layout was, and I was obsessed by it, but I didn’t think there was anyone else. I thought, well, maybe in the world there might be a handful of other people that are interested in it too.

Dan Heaton: No, it it’s crazy. Do you think about, you mentioned the merchandise because now in Florida they have the entire shop next to the Mansion with all that kind of unique merchandise. It’s crazy.

Tom Morris: Yeah. It took a long time for this to gain momentum because when in the mid eighties I was at WED, WDI, when you’re a young designer there, it’s a good thing. Most will do this for a couple of years, they’ll go to the park and work from the park and get some experience working from the Show Quality Standards office there.

So I was doing the first Churro wagons and some things like that, and I thought, why isn’t there a hearse parked out in front of the Haunted Mansion that sells cool Haunted Mansion stuff? You could call it gruesome gifts. I did a sketch of it and everything, which I probably still have on tissue paper somewhere. There was just no interest whatsoever, no interest. Like you and three other people would find that interesting. That’s just how it was. Even in the nineties, I kind of remember that it hadn’t really caught on. I think it took the Internet to do that.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I think so.

Tom Morris: I think people individually, they may have had their own little collections or sense of affinity, but it certainly wasn’t a community and there was certainly no cosplay or anything like that. It was even kind of a hard sell sometimes just to sell the attraction in the next park that we’re doing, because I think there was a time, and everything kind of does everything, every film, every car, every great design goes through a shadow period where people are kind of tired of it for a while and that can last 10 or 15 years before it kind of gets rediscovered and reincarnated and glorified.

So I kind of remember that period of time of Haunted Mansion where people didn’t really, it didn’t seem like anyone else cared about it. It’s really kind of weird. It is hard to imagine that it could have, knowing what we know now that it could have ever had that time period. But I think it did. I think that was kind of the eighties through or the mid-eighties and the nineties.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I think so because I, I grew up during that time and even into the nineties was in college and I remember it was a cool ride, but it didn’t seem like this. I mean the lines are longer and they have special events and it’s crazy. But I know you were part of the panel which had Tony Baxter and Bob Gurr and yourself and Tania Norris who helped to design the mansion. But I also know you did your own presentation on some of the early, you mentioned the building earlier with how it is in California. So I think you’re also, correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re doing a book not on the Haunted Mansion, but on Disneyland. Can you tell me about where that project might go and what you’re doing there?

Tom Morris: There’s two books that I’m working on right now, and one is just on speculation that someone will pick it up, although Disney editions has expressed interest in it in the past, and that is the archaeology of Disneyland. So that’s diving in deep into the bones of Disneyland, going all the way back before Disneyland was there and doing before and after. Comparisons, very precise ones. I mean, you’ve seen kind of basic ones maybe on the Internet, but this is really exactly where was the alligator pool in relation to the rest of Adventureland? Where is it? That’s where you see the film footage of Walt walking around before when it’s still orange groves. Where is that? What’s the evolution? How did these buildings evolve?

What’s still there from the beginning and doing it in a National Geographic style with cell overlays or doing it electronically where you can hit a button and watch a progression or a sequential progression of evolution of a building or an area within Disneyland that is one that I’m working on that has kind of taken a backseat to the other, which is I think a real project and I’m getting cooperation from all divisions of Disney to do it. It’s going way back to the very beginning of Imagineering. And this was really the result of doing the research for the first book.

I kept coming across names that I had never heard of before in doing this research like Tania Norris, but there are many, many, many others. I’m like, well, so who are these folks and where did they work from? I always had this curiosity even when I started at Web. So what were the old lead offices? What was it like when it started? There wasn’t a lot of memory about it. The memory seemed to start around 1962 when WED moved from the studio to Glendale. Then some of that memory got erased when they moved to the 1401 building first they were in a smaller building on Sonora. So I found that every time they did a big move that there was a lot of memory that seemed to get lost.

So it really is the archaeology, the early archaeology of WED Enterprises from the very beginning, ‘53, ‘54 through about 1970. That’s what I’m concentrating on because I’m finding people that are still around from 1955, everyone knows about Bob Gurr and Don Iwerks, but there are others that go back that far who can remember the setup, who can remember other Imagineers that you haven’t heard of and can remember where they worked from and where they did mockups at the studio where certain things were conceived.

That’s what I’m working on right now, and I’m hoping it done by next spring, submit the first draft anyway, and then we’ll see how it goes from there. But I’m tracking people down and I’m interviewing folks that are in their eighties and nineties, and it seems like that was a higher priority than the archaeology book people that can remember this is kind of the last chance to get thoughts and memories of a WED Enterprises Imagineering that you never seem to hear about or see photos of.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, that’s really interesting to me because I even think about, I’ve read a decent amount in history of WED and everything, and a lot of it, like you said, it goes mean now. We hear from Bob Gurr and Rolly Crump a lot and a lot of the Imagineers too that were involved in the ‘64 World’s Fair. Even for me, I hear a lot of people that worked on EPCOT, but like you say, when you go before the Tiki Room, I’m going, what was the group like that did the Subs and the Matterhorn and some of the things before that?

Tom Morris: Exactly. Where were those conceived? What did it take to get those things off the ground? There was a mock up for the Submarines on the studio lot. There was a test track for the Matterhorn up in Mountain View, California. So all these things that aren’t quite as known and you haven’t seen photographs of, or maybe you’ve seen one photograph, but you haven’t seen the other 23.

There’s also a bunch of Imagineers that you’ve never heard of before that were there for a long time, and that made major contributions, maybe not in the way that Marc Davis and Claude Coats and all the others that we read about all the time, but kind of the next tier down. A lot of draftspeople, draftsmen and draftswomen, cause they had draftswomen back then that did the final design, the final figuring out of what something would look like.

They tend to be forgotten because they’re working under the direction of an Art Director. But sometimes the Art Director gives them more responsibility or less responsibility, but often more responsibility to really come up with what the thing should look like. Even the first Art Directors at Disneyland are not really known. We’ve heard of Harper Goff and Bill Martin, but most people have not heard of Wade Rubottom and George Patrick. So these were some of the first art directors, and then they had key draftsmen that they relied on.

They were architects, many of ’em were architects, but almost all of them were from the film studios and had worked on fantastic projects, famous projects, and just never got screen credit at the studios that they were working at or at Disney. Just never got the limelight.

I’m kind of in the middle of all of that right now, kind of sussing through about a hundred drafts. People who were there from ‘53 to 1970 most of came from the Studios. And there were several women in that group and immigrants in that group. It seems to be quite interesting, although a lot of ’em are really hard to track down information on, and I’m enlisting some folks to help me with that right now. I’ve been visiting, I’ve been leading a very boring summer, a very boring year in general.

I go from library to library and collection to collection, trying to hunt down this information. That’s one of the reasons I want to get it done a year from now next spring, so I can like, okay, move on and onto the next project because this has really taken me back to black and white times. It’s both rewarding, but it’s also kind of weird to spend so much time 50 years ago. I’m spending a lot of, I feel like I am spending time going back in time to these places, and in the case of when I’m interviewing some of these folks, I am talking to these folks who started, who were there in the WED office in the 1950s or in the machine shop.

Dan Heaton: That sounds fascinating though, for a book just because, yeah, I mean, I can imagine that it’s not something where you can just go grab the most obvious sources because if you could, there’s books like you mentioned about people that mentioned Harper Goff and a lot of people like that, but they’re not going to, because like you said, it’s hard and plus people are getting older and unfortunately aren’t alive anymore.

So that it sounds like a real challenge, but also something that could be really rewarding. I think there’s a lot of people out there that would, like you mentioned the few names you mentioned that were lesser known. I’ve never heard those names before, and I think it’s probably pretty common for people beyond your super historians that probably is a pretty small number of people.

Tom Morris: So there’s that aspect of it. Then I don’t think I would do it if there wasn’t visual material to support it, because just going through a book of text and interviews and dates could be pretty dry. I found a lot of fantastic photographs.

There’s still photographs and the various Disney photo archives that haven’t either been published or people don’t even know that it might be the WED office over at the studio, which you never see photographs of, or these people that are in some of these photographs might be Imagineering or some of the things that we’re seeing in the photographs are mock-ups that may not be clear immediately when you look at, and then on second glance you go, oh, wow, that’s a mock-up I didn’t even know existed before. So there’s that, and then I’ll be doing diagrams and maps and showing where the photographs were taken.

So it is kind of along the lines of my archaeology studies that I’ve done. I’m going to pinpoint exactly where in all of the buildings and where at the studio, these photographs that you haven’t seen were taken, but also the ones that you have seen because a lot of photos that you’ve seen of walking around with mock-ups or with Imagineers goofing around. So I’m going to pinpoint where all of those exactly those were. So I think it’ll be great for the Imagineers to see. Not everyone can go on campus to those places, but I’m hoping that the Imagineers will get a kick out of that. But I think it’ll be interesting for anyone because they’ll get to kind of see a layout of how some of those buildings were back then.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, for sure. It sounds like an awesome project. Well, I want to make sure we have a chance to talk about some things you worked on, and even you mentioned just your interest in Disneyland, which is so strong when you were younger and even as you were growing up and getting into Disneyland even before you started working there, how did you get, so even in Disney or in wanting to work there when you were a kid?

Tom Morris: I was equally interested in architecture, animation, film, and Disneyland, Disneyland, maybe a little bit less. I would think that animation at the impressionable age of maybe eight or nine, I think it was animation that first caught my interest, and it was probably The Jungle Book that did it. But we also had to watch, we had to watch films like Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom, and Donald in Mathmagicland in school, so we were exposed to a lot of great Disney animation.

The music always fascinated me. I always liked the Disney music and The Jungle Book had great music. Mary Poppins had great music, the shows that were on The Wonderful World of Color at Disney, a lot of animation and a lot of great music. So I think that fascinated me and architecture fascinated me. My dad was a high school art teacher and sometimes English, but mostly art.

He also was in the theater department and built the sets for the stage shows. So that kind of interested me. Then my dad got a summer job at Disneyland in 1967, so he was hired as a seasonal employee as many high school teachers are, and he got to work the first summer on Pirates in the Caribbean.

One of the people that I was kind of thinking back on this, how did he know so much about how it was all done? More part of it was through his, I’m sure his expertise in knowing how everything was put together. But I think he had a really good, there was a format on that that I think would show you, would take you around if you were interested and let you go in further detail. I think this guy worked at Disney University was one of the orientation leads, and so he always had stories.

I guess my dad would get the stories from this guy, what was going on with the Haunted Mansion. When I finally went on it in the summer of ‘67, I was expecting something kind of cool. I had not heard that there was going to be a pilot ride. I wasn’t aware of it until my dad started working on it. So then I heard about it, and then there was the magazine article about it.

So finally we get to go on it and it affected me. I mean, I just didn’t expect it to be so good, and my dad was telling me a few little secrets about it, and that just kind of fueled the fire a little bit more. So ever since then, I started getting interested in the architectural and building side of things. I guess it just seems like a more interesting field to get into than an insurance salesman or a professor or what we were all pushed into in the sixties and seventies was be a business person or be a lawyer or be a doctor. So this seemed a lot more interesting.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s funny that Pirates, I’ve talked to multiple people who that Pirates at Disneyland, they wrote it when they were younger or even you mentioned that booklet with one person brought home and studied it. It’s amazing how much we mentioned the Mansion, but how much Pirates and even the Mansion led to so many people to get into some type of theme park design or something related. Those were huge, especially for kids of a certain age.

Tom Morris: Yeah, I think that was crazy in summer ‘67 because not only was there Pirates, but there is more. We went into Tomorrowland and there was all of that, which I had no idea was being worked on either. And it was all open. There was Carousel of Progress and Adventure Thru Inner Space and Circle Vision, People Mover, all of those things. Wow. I mean, my head was spinning. It was just kind of incredible. Yeah, I think a lot of us who were at that age or around that age really were affected by that, and it was kind of like something to be interested in. Besides, it wasn’t much interesting to be interested in. It was sports or politics or academic, just the academic world of you can be an engineer and work for Northrop.

I was just not interested in that. So I think there was a lot of people, a good percentage of people whose film and the arts, and it wasn’t something that you were encouraged to get into. You had to kind of fight your way to stay in there because your counselors and you didn’t get a lot of support back then because it seemed like a crazy thing. People didn’t even know what Imagineering was or when was. Animation, I think there was a perception that it was a dying art, and it was so you weren’t really encouraged or pushed into those fields, maybe film. It was funny times.

A lot of us now, Don Hahn was on that panel and he has similar memories of his childhood, and I’ve heard Brad Bird and others talk similarly of there growing up during that same period. Here was this thing, Disneyland that seemed like a much more interesting thing to get into or the Disney Studios and animation.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, it’s crazy to think about because I look at it now and Imagineering, even if you’re not an obsessive Imagineering, it’s like, oh yeah, Disney, they make attractions and such. You mentioned Brad Bird, and there was the arts class that they put together, which had had so many people, John Lasseter and others that ended up basically leading to what happened with the Renaissance and then with Pixar and then with parks. It’s crazy. But that was all into the seventies. That was after all of this, but still early for the time.

Tom Morris: And I remember my counselor saying, don’t you dare think about going to Cal Arts. That’s just a school where they’d smoke pot and goof around all day. It did get off to a rough start in the earlier seventies. Okay, I guess I won’t think about going there. Yeah, it was really it crazy. But Disney was also talking about, that was at a time when they had just opened Walt Disney World and now they’re talking about doing a thing called EPCOT and all these other projects that they had on board, and they were actively looking for recruits and they had a very active internal recruiting program, which is how I got selected to go up to WED.

Then it became an aggressive external recruiting program too with advertisements in the paper and magazines that Mickey wants you for EPCOT and for Tokyo Disneyland and all these other things as well as animation at the Studio. They were also beginning to aggressively look for who are going to be the breed of animators at the Studio. So eventually a lot of us came back together years later, kind of shared the same stories, but at the time, you kind of felt like alone party of one with that field of interest.

Dan Heaton: Well, let’s dive into EPCOT because I know you ultimately ended up working on that project and I believe started out doing some work for World of Motion and then for Imagination. So how did you get there and what was that like?

Tom Morris: Disneyland had a recruiting program that started before they announced EPCOT, which was just an internal career placement program that you could submit a resume and a portfolio and they’d keep it on file and they just have this file. I guess I didn’t know if I believed it. It’s like, is this just a thing where they’re making you feel good, but it really isn’t a thing that they’re ever going to go into?

So I did submit a resume, and I was probably in my first year of college, freshman year in college. And I probably submitted this thing a resume, and the portfolio would’ve been whatever I did in high school. I went to Cal State Fullerton, and I was taking communications and I was taking so long, and I think I took an illustration class; I wasn’t doing a lot of art at that point, but in high school I had done more art and I had done a lot of drafting.

I took three years of drafting. So I was a very good draft person with good spatial management knowledge and some architectural knowledge, although I wasn’t going to major in architecture, but I had the knowledge that it takes to plan a building or plan a house. So I submitted that not thinking it would be useful for three or four years or five years. Then they announced Epcot and they got back to me, this was like a year later and said, are you interested in going up to WED?

We’ve got your portfolio and they need drafts people, and we can see that you’re a good draft person. So I interviewed, and at the time I also knew Tony Baxter, so he had already given me a tour of WED, and I had taken tours at the Studio as well and had kind of decided that WED was more interesting at the time than the Studio was.

So I took this interview and they said I could start immediately, and I’d only been through a year and a half or two years of college. I thought, well, okay, I’ll try this out for a year and see what it’s like. And I never looked back. I never went back to college, so I didn’t finish. I just kept working. So the first thing I did was I was hired as an apprentice person in the Show Set Design department. And at first you do just work for a month or so, just labeling architectural plans or layouts or doing presentation.

You’re assisting with presentation materials, putting orders on site, plans of Tokyo, Disneyland or whatever. I don’t even know if I was doing that for a month before I started working on World of Motion, just doing some little in-between stuff that they had kind of last minute. And I guess design the scene where they’re inventing the wheel and there’s a used wheel salesman or something, or a used chariot salesman.

I was asked to design the Greek temple and the pagoda for that. So oftentimes, I guess the process is, and a lot of times the Art Director or the Key Designer will do some drawings, give it to the Model Shop, Model Shop will make the model, and then the next stage, the last stage is kind of the Show Set Designer draws it up and sometimes it gets back, it goes backwards, and there’s not enough either model builders or designers.

So I designed the temple and that pagoda, and I guess they liked what I did. There was a seam that hadn’t even been designed, which was the hot air balloon seam. So I laid that out and laid the buildings out and came up with an idea for what would make the scene funny. They didn’t like that idea, but it was kind of close.

The hot air balloon was about to get punctured by a steeple, like a church steeple or something. It had this Claude that I was working with Claude Coats on that scene, and he didn’t think it was very readable, but the rest of the scene I think was done as I drew it up and I had goats, I think in the basket, and I think it was replaced with the pig if I’m not mistaken. I went on to the next thing; I didn’t even look back.

I didn’t really pay attention to how that scene even came out, but I do remember there were a lot of people working on that project. So I think Marc had finished up, Marc Davis had finished whatever work he was doing on it. Claude was working on it, but so was Ward Kimball and some were other art directors that were pulled in.

So it was hard to figure out who I was even working for, but I think as far as I was concerned, I was working for Claude on that one. So I designed that scene and then next thing I knew, I was selected to work on Journey into Imagination, which was a late comer into the lineup for EPCOT. When I started there, there was no such thing as the Kodak Imagination Pavilion. So all of a sudden Kodak’s on the scene and they wanted do a pavilion called Images on Imagination.

Tony Baxter was selected to be the Creative Director Lead on that, and he had to assemble a team quickly, and there weren’t very many people left because everyone was working on trying to get World of Motion and Energy and The Land and all these other things. So Tony put together a team and he asked that I join the team.

At first it was just brainstorming. It wasn’t doing any kind of deliverables, it was just, what is this thing going to be? And Barry Braverman was on that, and Bob Rogers, who later formed his own company, he was on that, and Steve Kirk and a few other people, Tad Stones at some point came on board. So we just started brainstorming this thing, and then I was asked to start laying out. There was no architect available.

So since I had some architectural stability, I could lay out a building and I guess I could lay out a ride, although I had laid out or about it before, and just learned the same way the first Imagineers learned back in the fifties and sixties. You learn by doing, you just jump into it and do it. So three years of working on Journey into Imagination, basically doing the layout, designing that complicated scene with the hot air balloon, the Dream-Catching Machine.

I designed not only the machine, but all the components in that scene and how they would work and how it would be timed out when the cars would come in, when they would turn, what the sight lines were. So you wouldn’t see things that you’re not supposed to see that are just barely out of line of sight behind clouds or other things in there. But I must say that that Dream Catching Machine was the idea for it came from Steve Kirk and he built a beautiful model of it.

So what I did was refine it and I added a few things to it and just made it even, I guess, better than what Steve came up with was great. I just wanted to make it that good and even better. So I really shepherded that turntable scene and then the scene that followed it and then worked on some Image Works things too, and then got sent out to the field and lived in Walt Disney World for a year in the campground. So that was kind of the first big job.

Dan Heaton: So with Imagination, I mean that list of people that you mentioned, I mean is stunning. Bob Rogers from BRC and Kirk and Tony and yourself.

Tom Morris: To me, Skip Lang was, he was Skip. Skip really built everything. I mean, he really figured out how to do everything. We were dreamers and designers, but Skip had to figure out how to actually make things work.

Dan Heaton: Which is a challenge for that ride because I mean with that turntable, it still kind of baffles me how all that worked, especially building it in for an ‘83 opening. I know you worked on the design, but how tricky was that, even just from what you know about to get that to work?

Tom Morris: For me, it was tricky from a timing and sight line standpoint. I had no idea it was going to be tricky for the mechanical standpoint as well. I just assumed that’s a big machine and some smart engineers will figure out how to make the big machine turn. It was a little more complicated than that because a lot of it was cantilevered. A lot of the sets were cantilevered. So structurally it was kind of a beast that I probably underestimated how difficult it would be to actually manufacture this thing.

It was built by one of those companies that does rotating restaurants. So same company did the turning restaurant in the Land Pavilion next door. I can’t remember the name of that company. We went up to their offices in San Francisco. I think it was, from my standpoint, it was timing. It was all about how the cars would get in, how close together can you get the cars, because the widening of cars were the worst. The sight lines, the was the sight lines were so you wanted good sight lines, so you really wanted every seat to be kind of a sweet spot, which meant you had to space the cars a certain way and you had capacity concerns.

You had speed concerns, you had safety concerns, you had acoustic concerns because you didn’t want to hear what was going on in the adjacent theater. There were five of these things on the turntable, there was apparatus on board, there was a puffing machine, there was a CO2 tank. All of that had to be hidden by set pieces that looked like clouds. So that was the hard part as far as I was concerned. And I wasn’t really thinking about from a mechanical standpoint, how difficult, how do you get sound onto the turning turntable? You can’t have a hard cord.

So these are things I just figured someone else would figure that all out and they did, but it was a little more complicated than I guess I first imagined it would be. There was a big center core in the center of it. There were windows. It had windows because you had to isolate the sound, so that center core was isolated, so so the sound wouldn’t go from theater to theater.

There were columns in the middle of all of that that had to be worked around. It was a big thing. I did end up working on it for quite a long time. Then also in the field troubleshooting a lot of the conditions that kind of show up right there in the field as you construct the thing and pull everything together. So it was a big thing. It was a big deal but I wish that turntable was still there.

Dan Heaton: Oh, it was such a brilliant attraction and I understand things change, but I didn’t appreciate it enough. I was younger and such just how remarkable. I mean the fact that just doing the turntable is one thing, and then there was another 6, 7, 8 minutes of the ride after that. It’s like that was just the beginning. That could almost be its own thing.

Tom Morris: Originally there were going to be two turntables. It was going to be the introductory one and then the finale one. That was my first experience with budget cuts. I had designed that pavilion so that it would disembark on the upper level right into the Imageworks, so you didn’t have to go up a set of stairs. So that got cut and the second turntable got cut, and it’s kind of too bad because it affected the flow of that pavilion. It was really going to have a good flow where you disembarked on the upper level and then you trickled down back to the first level and over to the Imageworks, and there wasn’t any cross traffic or anything like that. That was a budget cut.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I’m sure you dealt with a lot those over the years.

Tom Morris: Well, yeah. You know what I mean? I guess that’s how it went. You design the way you think it should be and then you go through a budget type thing. But we were so late, we had to open the same time as everything else, so there wasn’t much time to make a thoughtful adjustment, I guess. So we decided to do it and then open the thing on October 1st. The ride did not open on October 1st, although I think we took Kodak around a month later for their opening ceremony. We got it to work just enough to cycle a group of people around, and then it had to close for three months.

The show was almost finished in October, but the ride had a lot of ride control things that had to be worked out before we could let guests go on a regular with a regular throughput. And everyone was all the ride engineers and busy with the other big attractions like the Energy show and the Spaceship and all of those. So that’s why it was delayed. Imageworks was open on our opening day and the film was there and the leapfrog fountains, that was all there, but the ride took a little extra time.

Dan Heaton: Well, it ended up working out great. I know I’m going to jump way ahead here. Ultimately, I know it wasn’t at first but you had the chance to design the Sleeping Beauty Castle. And so going into that, I guess I’ll start first, what was it like with coming in as a Show Producer and having your ideas of what you wanted to do and what adjustments did you make when you took over?

Tom Morris: I think I was the last producer brought over because Fantasyland already had selected its team, and I was down at Disneyland working on Disneyland projects. I had just finished doing the first layout of Splash Mountain and handed that over to Bruce Gordon. I had been working on some preliminary stuff for Indiana Jones, and I think I worked on the facade, the architecture for Star Tours for that south building in Tomorrowland. And I did all of that from the entrance to Star Tours all the way wrapping around to Star Traders and did the neon and all of that.

I had taken a trip to Europe, my first trip out the country, and I just happened to visit a lot of little medieval villages in Germany and France and had taken a slew of photographs, castles also. So I kind of had those in my back pocket, and they had already selected the group for Euro Disneyland, but one of the show producers was moved over to Disneyland, and that opened up an opening for a Show Producer.

Tony asked me to take that role, but land had kind of already been designed. So I started that under the caveat that there wasn’t much design left or much latitude to leave my creative imprint anywhere. The castle was still being worked on. There were like six or seven people doing castles, and there were too many people already working on castles. So don’t you want one more yet another person burning hours in time working on a castle?

But I kind of had in my mind what I thought because listened to how he would explain what he wanted, and I thought I understood what he was saying, and the other folks didn’t quite seem to even understand what he was saying, or they just wanted to do something completely different. There were some really cool concepts like Tim’s concept. It was really neat for kind of an Art Nouveau modern kind of a castle with a very distinctive French influence to it when else was doing, there was just a lot of people doing castles.

I just kept thinking, well, I think I know what Tony wants, but I’ll be quiet. And I guess after a couple months of that and people were still getting nowhere, I asked Tony, let me put together a board like inspiration board, hearing you say Storybook Castle, Fairytale, more like the Disneyland castle than the Disney World castle. So I put together a style board, I guess comprised of photographs of castles from other Disney films or other film projects entirely, or storybooks, Disney and non Disney. Then I actually started just doing some scribbles, and I guess he liked that direction. So eventually I started designing the castle. That’s how it happened kind of by accident, I guess.

Dan Heaton: So what was the secret? What was the trick that made your castle work for what Tony was looking for? I mean, all the castles are great, but that one in particular is really stunning. So what was the trick that you mentioned you knew what he wanted.

Tom Morris: There was kind of a long shot idea as well as a closeup idea. The long shot idea was something that was tall and slender and was inspired by what I saw in France at Limoges, which is not a castle, but it’s castle like it’s a village on a rock in the middle of an estuary that fills up with water half of the day and then drains. So there was something intriguing about that to begin with something that, a castle that would feel like it’s rising like a mirage from the water.

So that was kind of the long shot idea. Then the closeup idea was he kept mentioning the Disneyland castle, so I know exactly what he meant by that. It’s, there’s a certain type of detail. It’s a softer rounder, I guess, more gothic and more medieval. Whereas the one in Florida is gothic and renaissance.

It’s a little sharper. It’s also very close to what all the castles been nearby in the Loire Valley and other nearby regions in France. So that’s why it seemed like it was not as appropriate to use, because even though it’s a beautiful castle, it’s also very reminiscent of nearby castles. So it wouldn’t stand out as much. The use of stone, the stone textures on the Disneyland castle is a different stone texture than what’s on the castle in Florida. The plaster is different, the windows, there’s also a little bit more Romanesque influence just earlier, I guess. So I just kind of intuitively knew what he meant. But then I guess the third thing was how do you arrange towers and turrets in an interesting way? And I had been building sandcastles. I grew up at the beach, so I was just used to doing drift castles.

I drew a lot of castles in my spare time in school; I drew up that castle for the literature scene and Journey into Imagination. And I had done a castle rendering, I think, in high school. So I kind of was opinionated about how a castle should look like, not too blocky and fat, not too squat, not too skinny, the right kind of combination of negative space and openings.

You want little archways. I always love that little archway on the Disneyland castle on the left. So I kind of glorified that a little bit. One of the castles that was an example from a storybook, I think had a little spiral staircase. So I really loved that it gave it kind of a stimulus very, I dunno, French look to it. So I just had a gut feeling for how it should be.

I worked with the model builders too, to make sure that the towers were arranged in a way that would always look good as walked around it. It wouldn’t fall apart or look too blocky. So the Disney World castle is perfect when you walk around that castle from every land, it’s perfect. There isn’t a bad side to it. Disneyland has some funny sides to it where it kind of looks even smaller from some angles where it just kind of looks kind of funny from some angles. So I didn’t want that to happen. So I just worked really closely with the model builders and we started this thing with wooden dowels, arranging them in a way that would look pleasing.

Dan Heaton: On a similar note real quick on the castle, how did the dragon end up there? Because I feel like that’s a really unique thing with Paris that I think is a touch that a lot of people who visit for the first time, like myself when I went, or really appreciate the fact that that’s an extra touch. It’s almost part of the castle in itself.

Tom Morris: So totally. So I’ve always had this thing where you want to explore every nook and cranny of something. I guess a disappointment with both the castle at Disneyland and the castle at Walt Disney World is you don’t get to explore it enough. There’s not all these little staircases and places to go, and it should be like the caves and Tom Sawyer Island sort of where you just like, oh, I want to see what happens if you go left.

Where does that passage weigh on the right go? So I wanted a little bit of that element. In the castle, we had the opportunity to do so because we kind of needed instantaneous capacity places for people to be. I think as we went along in the project, there were opportunities for more capacity. It’s like, oh, the projection for the attendance went from nine to 10, so now we need more instantaneous capacity.

So hourly capacity manifested itself with a hedge maze, which was not an original menu item. It wasn’t an attraction when I came on board, but they needed like another 1,200 and not a big ride that would be expensive and something that would be less expensive. Also the opportunity to do an upstairs area where people could meander, and also a downstairs area where people could meander.

And because of the dragon moment at Tokyo Disneyland was so popular and we had the tooling for it, it just seemed to make sense to have a dragon down there. There was the room to do it because we sunk that moat pretty low. We also raised the breezeway, or the draw bridge or the approach up to the castle kind of went up a little bit steeper than at other parks. Then the moat was down deeper. So there was actually kind of a big vault down there anyway that really presented itself with an opportunity to put something down there.

Dan Heaton: Just in general about the Paris project, I mean, I look at each of the lands. You had Eddie Sotto on Main Street and then Jeff Burke and Tim Delaney and yourself and Tony, of course. I mean, what was the creative environment? I feel like that park was a culmination of all these younger Imagineers that came in around Epcot around there, and then just were let loose on this park in Paris.

Tom Morris: Right. Well, and Chris Tietz was part of that too. He got Adventureland and Pirates of the Caribbean. I think in a way, we were typecast, although I really wasn’t a Fantasyland guy at the time. Most of the stuff I had done was either Tomorrowland related through Epcot, through some projects I had done in Tomorrowland, not just Star Tours, but I did some other smaller jobs throughout Tomorrowland. Throughout Epcot, I had done some Frontierlandish stuff, and I don’t even know if I had done anything kind of Fantasylandish other than that castle scene in the Journey into Imagination.

But somehow Tony, I guess intuitively knew where our strengths were. So I guess how he selected the original Show Producers/Art Directors for the lands, I don’t think he could have gotten anyone better to do each of the lands. Plus Skip Lange was kind of parkwide on a lot of art direction, miscellaneous art direction, but certainly a lot of the rock work and those rock work and stone work and all of that.

John Olson and Ron Esposito with the color and the paint, and Katie Olson as well. So we had the best people at the time. I think we were, I guess the second generation of Imagineers, and we were the generation that grew up fans, I guess all of us. Maybe that’s why he selected us. He knew that we were kind of fans and we had our particular interests in those particular areas. Certainly had a lot of interest in the space program and the seas and all of that. So that’s how it all came about.

Dan Heaton: Well, I mean, I think the fan point is good because that park as a fan, you go in there and just getting to see these different versions of Pirates and Haunted Mansion, Space Mountain and everything is pretty amazing to see. So I know we’re getting short on time, but I had one more kind of general question for you before we finish. Yeah. So I mean, you worked at Imagineer, you started before around Epcot, and then were there all the way through Cars Land and Radiator Springs Racers, which I know you were very closely involved with.

What’s the biggest change in how things work, or what’s one big change that you’ve noticed beyond just, oh, the technology’s better in terms because I mean, we’ve seen it where Disney, they’ve got Galaxy’s Edge and they’re doing all these things and Universal’s growing and the industry is just exploding. But in terms of the design, if you were working, how did things really change for you in terms of how you did things?

Tom Morris: There’s a lot more people and a lot more money. I mean, there’s actually decent budgets now, and there’s a lot of, you kind of get the resources now that we weren’t always privy to back then or the budgets, and that’s a great thing. But also at the same time, because the industry is growing, the resources can be thin sometimes. So sometimes you don’t have all the people that you need. You have people, but not the ones that you need, if you know what I mean.

There’s a finite group of people and it’s growing, which is great because more and more people that are interested in getting into the field, but depending on the project that you work on, sometimes you don’t always get all of the people that are qualified. So that means you’ve got to instruct and teach, which kind of puts you in a different frame of mind.

You’ve got to become kind of a mentor and shepherd some folks along. And that’s fun to do. It’s rewarding to do if it’s a big project and you’ve got a lot of folks like that, that can become really challenging and time consuming. So I think it’s the challenge for the industry is this is the kind of thing that’s hard to teach in school, and you can teach some theoretical elements of it in school, but you really don’t get a sense of it until you’re actually at the board or in the field doing the work.

So I think just the numbers, the budgets and the number of folks it takes to accomplish these jobs has grown significantly. And that’s a double-edged sword. Definitely the technology is better. Definitely having people who have grown up loving the industry is probably the biggest plus, because I can remember some folks that when I started, it was just a job for them that was a small minority.

But there was were folks that were kind of just like, okay, well it’s five o’clock now, and so this is how it is now. This is how it’s going to be because I’m done and I got to go home on the weekends here. And you go, well, it doesn’t really look finished. So there was kind of a transitional period I think when the first group that worked on Disneyland and Walt Disney World were all from the film industry and all.

They worked either directly with Walt or people who worked directly with Walt. So there was just a seasoning there. There were seasoned people that kind of knew what to do. Then I think there was this awkward period in between about the time that I started where people were coming from other fields, and they weren’t fans and they didn’t necessarily know how to do a Tiki structure, and they may or may not have been interested in finding out or doing the proper research to figure that out.

So you’d get some not great design coming through. That was a minority, of course, it still was there. These were people that were not fans and they didn’t come from the film industry. They just didn’t seem as interested. So that was, I think, an anomaly during that period, and that now I think is gone, and people coming in now are in the industry because they want be in the industry.

They didn’t just fall into it. They know what they want and they know what their friends want, and they know what the fans want. So that is a huge, huge advantage over any time period, because they want to ride. They’re as anxious to experience the thing that they’re coming up with as anyone. So I think that’s the biggest bonus right now is that you’ve got people who really care and are excited about experiencing these shows, these rides, these attractions, museums, whatever they are, and they want to enjoy it again and again.

Dan Heaton: Yeah, I think that’s a great point. And you see it in a lot of medium. You see it with movies where people that loved Marvel comics are now directing movies or love Star Wars, like JJ Abrams or something that grew up with it or whomever. But I mean, I think that can only be a positive for theme parks because like you said, if somebody’s, well, I can tell from talking to you that somebody that obviously was a fan of the parks before you started working there, it had to have only been something that you’re going to be more driven and have more passion for it if it’s something that you already are interested in and love than the alternative.

Tom Morris: Right? I think that’s the number one thing right now that’s really going to, I think, propel the industry forward.

Dan Heaton: Well, excellent. Well, Tom, I put together a big list of things from your career, and I said before we started that we wouldn’t cover all of them, but I was totally right. Because there’s so much to cover and you had such great stories, I feel like we could just talk about the Haunted Mansion for three hours, which is great too.

Tom Morris: We probably could. Yeah. That leaves more for next time, right?

Dan Heaton: Definitely. Yeah. I would love to have you back, especially as you’re getting your book together, which sounds fascinating. And plus there’s plenty of projects. We didn’t talk about Disney Quest and so many other things you worked on over the years. That would be awesome to talk about. But I know you have a pretty big social media presence, so if people want to follow you is where are the good places to keep track of what you’re doing with the book and other projects?

Tom Morris: Well, I think mainly Twitter, so I’m Tom K Morris on Twitter, and I’m also on Instagram. It’s less Disney centric on that, and I don’t seem to post as much on that, but that has a lot of my travel, a little bit more of my travels, although I’m not traveling a lot this year because doing this silly book. So I’m also Tom K Morris on Instagram. So those are the two main platforms.

Dan Heaton: Awesome. Well, Tom, thanks so much. I really appreciate doing the show and definitely excited about what you’re doing in the future.

Tom Morris: Great. Well, thank you so much. I enjoyed this.

Leave a Reply